Spider is an eight-legged animal that spins silk. About half of all known species (kinds) of spiders make silk webs. These webs range in appearance from simple jumbles of threads to complex, often beautiful designs. Spiders use their webs to catch insects for food.

All spiders have fangs, and all except a few have poison glands. Spiders use their fangs and poison glands to kill prey. A spider’s bite can paralyze or kill insects and other small animals. Although spiders feed mostly on insects, larger spiders may occasionally capture and eat tadpoles, small frogs, fish, birds, or even mice. Spiders frequently eat each other. Most female spiders are larger and stronger than male spiders, and they may attack males or young of their own species.

Spiders live anywhere they can find food. They thrive in fields, woods, swamps, caves, and deserts. One species, the European water spider, spends most of life underwater. Other species live on beaches between high and low tides so that they lie under salt water for part of each day. Some spiders thrive in houses, barns, or other buildings. Others prefer the outsides of buildings—on walls, on window screens, or in the corners of doors and windows. Spiders often live near lights that attract insects at night.

Many people think spiders are insects. However, spiders differ from insects in a number of ways. Ants, bees, beetles, and other insects have six legs. Spiders have eight. Most insects also have wings and antennae (feelers), but spiders do not. Biologists classify spiders as arachnids. Other arachnids include scorpions, ticks, and the spiderlike daddy longlegs (also called harvestmen). Both arachnids and insects belong to a large group of animals called arthropods, which have jointed legs and a stiff outside shell or skin.

Scientists arrange the thousands of spider species into more than 100 classifications called families. One family, the liphistiids, consists of primitive burrowing spiders. Liphistiids have abdomens that are visibly divided into segments. In all other kinds of spiders, the abdomens do not show segmentation. Scientists divide non-segmented spiders into araneomorphs, or true spiders, and mygalomorphs. More than 90 percent of all spider species belong to the true spider group. Mygalomorphs include tarantulas.

Another way to group spiders divides them into web-building spiders, which make webs to trap insects; and hunting spiders, which catch prey without webs. Hunting spiders catch food in a variety of ways. Jumping spiders, for example, sneak up and jump on prey. Crab spiders ambush their victims.

This article will describe the body of a spider, how a spider makes and uses its silk, and the life of a spider. It will then discuss different spider families and the ways spiders and people have interacted.

The spider’s body

Some spiders are smaller than the head of a pin. Others grow as large as a person’s hand. One South American tarantula can measure more than 10 inches (25 centimeters) long with its legs extended.

Spiders may be short and fat, long and thin, round, oblong, or flat. Their legs range from short and stubby to long and thin. Most spiders have brown, gray, or black coloring. But some types are as colorful as the loveliest butterflies. For many tiny spiders, people must use a microscope to clearly see the color patterns.

Loading the player...Spider anatomy

A spider has no bones. Its tough, mostly rigid skin serves as a protective outer skeleton. Fine hairs sprout from a spider’s skin. Many spiders also have bumps and spines (outgrowths of skin) on their bodies.

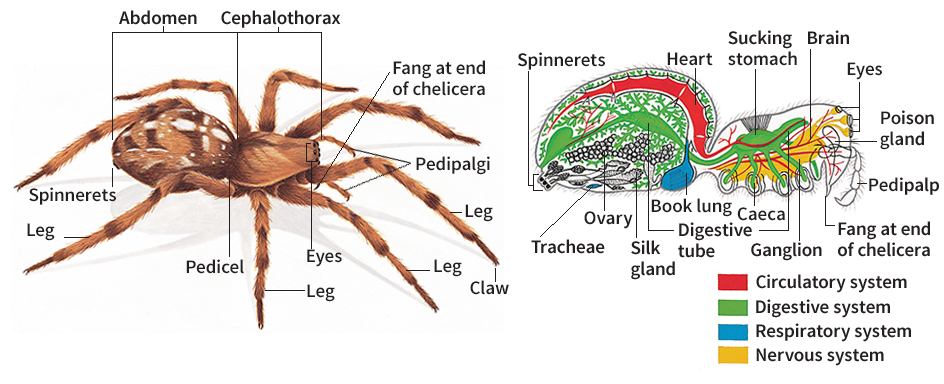

A spider’s body has two main sections, the cephalothorax, which consists of the fused head and thorax (middle section), and the abdomen. A thin waist called the pedicel connects the cephalothorax and abdomen.

Eyes.

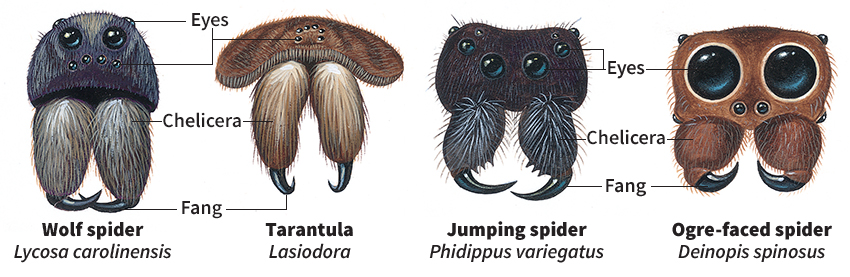

A spider’s eyes lie on top and near the front of its head. The size, number, and position of the eyes vary among different species. Most species have eight eyes, arranged in two rows of four each. Other kinds have six, four, or two eyes. Some spiders have better vision than others. For example, hunting spiders have good eyesight at short distances, which enables them to see prey and mates. Web-building spiders generally have poor eyesight. They use their eyes to detect changes in light. Some species of spiders that live in caves or other dark places have no eyes at all.

Mouth.

A spider’s mouth opening lies below its eyes. Spiders do not have chewing mouthparts, and they swallow only liquids. Extensions around the mouth form a short “straw” through which the spider sucks the body fluid of its victim.

A spider eats the solid tissue of its prey by predigesting it. First, the spider vomits digestive juices on its prey to dissolve the tissue. Then the spider drinks the liquid and repeats the process.

Chelicerae

are a pair of mouthparts that the spider uses to seize, crush, and kill its prey. The chelicerae << kuh LIHS uh ree >> are above the spider’s mouth opening and just below its eyes. Each chelicera ends in a sharp, hard, hollow fang. An opening at the tip of the fang connects to the poison glands. When a spider stabs an insect with its chelicerae, poison squirts through the fang into the wound to paralyze or kill the victim. Some spiders use their chelicerae to dig burrows in the ground.

The fangs of true spiders point crosswise and move toward each other. True spiders have poison glands in their cephalothorax. The fangs of mygalomorphs point straight down from the head and move parallel to each other. Mygalomorphs have poison glands in their chelicerae.

Pedipalpi

, also called palps, are a pair of projecting parts that look like small legs attached to each side of the spider’s mouth. Each of the two pedipalpi << pehd uh PAL py >> has six segments (parts). The segment on each palp closest to the body forms one side of the mouth. In most spiders, the mouth segment bears a sharp plate with toothed edges. The spider uses this plate to cut and crush food. In adult male spiders, the last segment of each pedipalp bears a reproductive organ.

Legs.

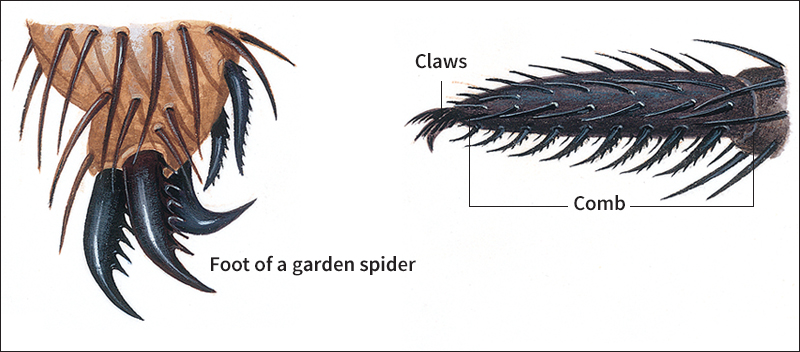

A spider has four pairs of legs, which are attached to its cephalothorax. Each leg has seven segments. The tip of the last segment has two or three claws. A brush of hairs called a scopula may surround the claws. The scopula sticks even to smooth surfaces and helps the spider walk on ceilings and walls.

Each leg is also covered with various kinds of sensitive hairs that serve as organs of touch and smell. Some hairs pick up vibrations from the ground or air. Others detect chemicals in the environment.

When a spider walks, the first and third leg on one side of its body move with the second and fourth leg on the other side. Spiders lack muscles in one leg joint and squirt blood into their legs to make them extend while walking. If a spider’s body does not contain enough fluids, its blood pressure drops. The legs then curl up under its body, and the animal cannot walk.

Respiratory system.

Spiders have two kinds of breathing organs— tracheae << TRAY kee ee >> and book lungs. Tracheae, small tubes found in almost all kinds of true spiders, carry air to the body tissues. Air enters the tubes through one or, rarely, two openings called spiracles on the abdomen.

Book lungs are cavities in the spider’s abdomen. Air enters the cavities through a tiny slit on each side and near the front of the abdomen. The wall of each cavity consists of 15 or more thin, flat sheets of tissue arranged like the pages of a book. Blood covers the inner sides of the sheets, and air covers the outer sides. Oxygen passes through the sheets into the blood, while carbon dioxide passes out of the sheets. Most true spiders have one pair of book lungs. Mygalomorphs have two pairs.

The European water spider lives mostly underwater. This animal “breathes” in water by carrying air bubbles on its abdomen. It fills its underwater web with air bubbles, which gradually push all the water out of the web. The spider can survive on air from these bubbles for up to several months, if necessary. It then has to return to the surface to gather more bubbles.

Circulatory system.

Spider blood contains many pale blood cells and has a slightly bluish color. The heart consists of a long, slender tube in the abdomen that pumps blood to the body. The blood drains back to the heart through open passages instead of veins, as in the human body. If a spider’s skin is broken, it may quickly bleed to death.

Digestive system.

A digestive tube extends the length of the spider’s body. In the cephalothorax, the tube is larger and is surrounded by an organ called the sucking stomach. Powerful muscles attached to the stomach alternately squeeze and expand it, causing a strong sucking action. The sucking pulls the liquid food through the stomach into the intestine. Digestive juices break the food into molecules small enough to pass through the walls of the intestine into the blood. The blood then distributes the food to all parts of the body. Food is also pulled through the stomach into fingerlike storage cavities called ceca, also spelled caeca << SEE kuh >> . The ability to store food in the caeca helps enable spiders to go for months without eating.

Nervous system.

The spider’s central nervous system lies in the cephalothorax. It includes the brain, which is linked to a large group of nerve cells called the ganglion. Nerve fibers from the brain and ganglion run throughout the body. These fibers carry information to the brain from sense organs on the head, legs, and other body parts. The brain can also send signals through the nerve fibers to control the body’s activities.

The spider’s silk

Spider silk consists of protein. The silk cannot be dissolved in water, and it ranks as the strongest natural fiber known.

How spiders make silk.

Silk glands in the spider’s abdomen make silk. As a group, spiders have eight kinds of silk glands, each of which produces a different type of silk. However, no species of spider has all eight kinds. Every spider has at least two kinds of silk glands, and most species have five. Some silk glands produce a liquid silk that dries outside the body. Other glands create a silk that stays sticky.

The spider spins silk with short, fingerlike structures called spinnerets on the rear of the abdomen. Most kinds of spiders have six spinnerets, but some have four or two. The tip of a spinneret contains the spinning field. As many as 100 tubelike spinning spigots cover the surface of each spinning field. Each spigot serves one silk gland. Liquid silk flows from the silk glands through these spigots to the outside. As the liquid silk comes out, it hardens. Using different spinnerets and spigots, a spider may combine silk from different silk glands and produce a thin thread or a thick, wide band.

Some spiders also can make a sticky thread that looks like a beaded necklace. To do this, the spider spins a dry thread and coats it with sticky silk. The sticky silk then contracts into a series of tiny beads along the thread.

Some kinds of spiders have another spinning organ called the cribellum. It lies almost flat against the abdomen, just in front of the spinnerets. Hundreds or thousands of spigots cover the cribellum, producing extremely thin fibers of silk. Spiders with a cribellum also have a special row of curved hairs called a calamistrum on their hind legs. Spiders use the calamistrum to comb sticky silk from the cribellum onto dry silk from the spinnerets. This combination of threads forms a flat or tubular mesh of microscopic fibers called a hackled band. The mesh entangles the bristles, spines, and claws of insects and other small prey.

How spiders use silk.

Spiders, including those that do not build webs, depend on silk in so many ways that they could not live without it. Wherever a spider goes, it spins a silk thread behind itself. This thread is called a dragline. The dragline is also called a “lifeline” because it can help the spider to escape from enemies. Spiders use their draglines to lower themselves to the ground from high places. When in danger, a spider can drop on its dragline and hide in the grass. Or the spider can simply hang in the air until the danger has passed, then climb back up the dragline.

Spiders also can use a special kind of fine silk to spin tiny bundles of sticky threads called attachment disks. Attachment disks cement the spiders’ draglines and webs to various surfaces.

Each kind of web-building spider makes a different type of silk retreat (nest) as its home. Some wandering spiders rest each day in a leaf that they fold around themselves and line with silk. Other spiders dig burrows in the ground and line them with silk. Still others build retreats in the center or at the sides of their webs.

Many web-building spiders wrap silk lines or sticky bands around their prey as they capture them. Some orb weavers wrap their victims with wide sheets like mummy wrappings so the victims cannot escape.

The life of a spider

Most spiders live less than one year. But large species can live longer. Some female tarantulas have survived more than 20 years in captivity. Spiders become adults at different times of the year. Some mature and mate in the fall and then die during the winter. Their eggs do not hatch until spring. Others live through the winter, mate and lay eggs in the spring, and then die.

Except during mating, most spiders are loners. But some species live in social groups. Certain kinds of spiders live together on a communal web. In one tropical species, for example, tens of thousands of spiders may share a web 25 feet (7.6 meters) long and 6 to 8 feet (1.8 to 2.4 meters) wide. Other spiders live close to one another in large groups, but each individual has its own web.

Courtship and mating.

As soon as a male spider matures, he seeks a mate. Most male spiders perform courtship activities to identify themselves and to woo females. In web-building spiders, the males usually pluck and vibrate the female’s web. Some male hunting spiders wave their legs or vibrate the ground in a courtship dance. Male jumping spiders use the colored hairs on their legs to attract females. In certain spiders, the male presents the female with a captured fly before mating.

Before he mates, the male spider spins a silk platform called a sperm web. He deposits a drop of sperm from his abdomen on the platform. Then he fills the organs at the tips of his pedipalpi with sperm. He uses the pedipalpi to transfer the sperm to a female during mating. After mating, the female stores the sperm in her body. When she lays her eggs, weeks or even months later, the sperm fertilize the eggs. Female spiders do not usually eat the males after mating, as some people believe.

Eggs.

The number of eggs that a female spider lays at one time varies with her size. Females of many species lay about 100 eggs. But some of the smallest spiders lay just 1 egg, while some of the largest lay more than 2,000.

In most species, the mother spider encloses the eggs in a silken egg sac. This sac consists of several kinds of silk, including one type used only for egg sacs. Egg sacs can have a complex structure with an outer papery layer, an inner threadlike layer, and a soft core to support the eggs.

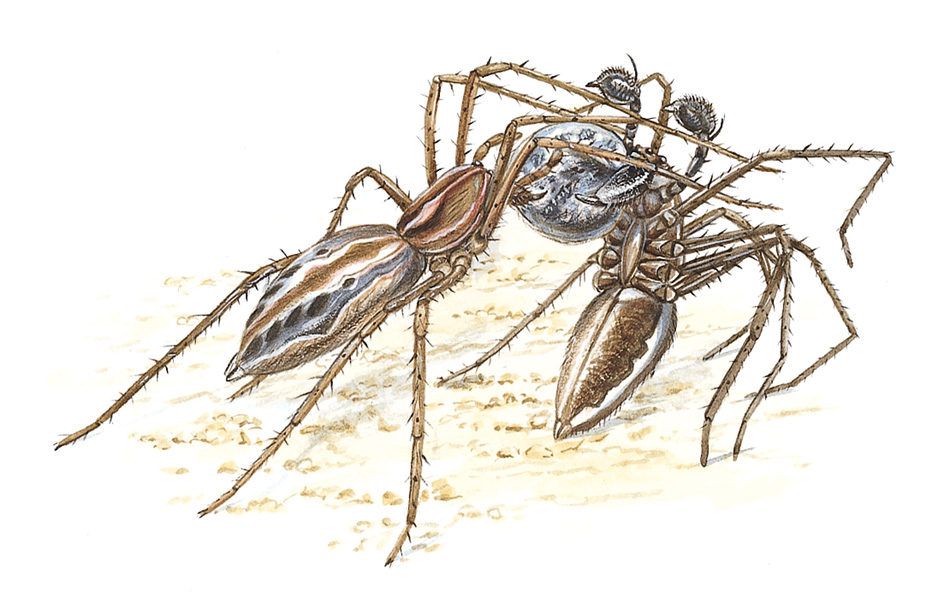

In many species, the mother dies soon after making the egg sac. In other species, mothers remain with the eggs until they hatch. Some spiders keep the sac in their web. Others attach the sac to leaves or plants. Still others carry it with them. The female wolf spider attaches the sac to her spinnerets and drags it behind her. Fishing spiders carry the sac with their fangs.

Spiderlings

hatch inside the egg sac. They do not leave the sac immediately because they are not yet able to walk or spin silk. After molting (shedding their skin) once inside the egg sac, the spiderlings are developed enough to leave. But they remain in the sac until warm weather arrives. If the eggs are laid in autumn, the spiderlings stay inside their egg sac until spring. After leaving the sac, most spiderlings begin spinning draglines. In a few species, the spiderlings remain for a time in the mother’s web and share the food she captures.

Many spiderlings move far away from their birthplace. To do this, a spiderling climbs to the top of a twig or some other high perch and tilts its abdomen up into the air. It then pulls silk threads out of its spinnerets. The wind catches the threads and carries the spiderling into the air. This method of traveling is called ballooning. A spiderling may travel a great distance by ballooning. Sailors more than 200 miles (320 kilometers) from land have seen ballooning spiders. But most ballooners travel less than a mile or kilometer.

Spiderlings must molt to grow larger. First they make a new, larger skin just beneath their old skin. The tight old skin splits. The animal then wriggles out of the old skin and plumps up the new skin until it hardens. Most kinds of spiders molt from four to twelve times before becoming adults. When mature, most spiders stop molting. Female tarantulas and a few others continue to molt even after they become adults.

Enemies

of spiders consist mainly of birds, insects, and other spiders. Pirate spiders eat only other spiders. Wasps rank among the spider’s worst enemies (see Wasp (Food)). Predators also include lizards, snakes, frogs, fish, or any other animals that eat insects. In addition, spiders suffer from fungal infections and from flies and wasps that live as parasites inside the spiders’ bodies.

Web-building spiders

Web-building spiders catch food by spinning webs to trap insects. A web-building spider does not usually become caught in its own web. When walking across the web, it grasps the silk lines with a special hooked claw on each foot.

Loading the player...Spider web

Tangled-web weavers

spin the simplest type of web. It consists of a jumble of threads attached to supports, such as the corner of a ceiling. Cobwebs are old tangled webs that have collected dust and dirt.

Cellar spiders spin tangled webs in dark, empty parts of buildings. One cellar spider that looks like a daddy longlegs has thin legs more than 2 inches (5 centimeters) long.

Cobweb weavers spin a tangled web with a tightly woven sheet of silk in the middle. The sheet serves as an insect trap and as the spider’s hideout. Also called comb-footed spiders, these spiders have a comb of hairs on their fourth pair of legs. They use the comb to throw liquid silk over an insect and trap it. The black widow spiders belong to the cobweb weaver group.

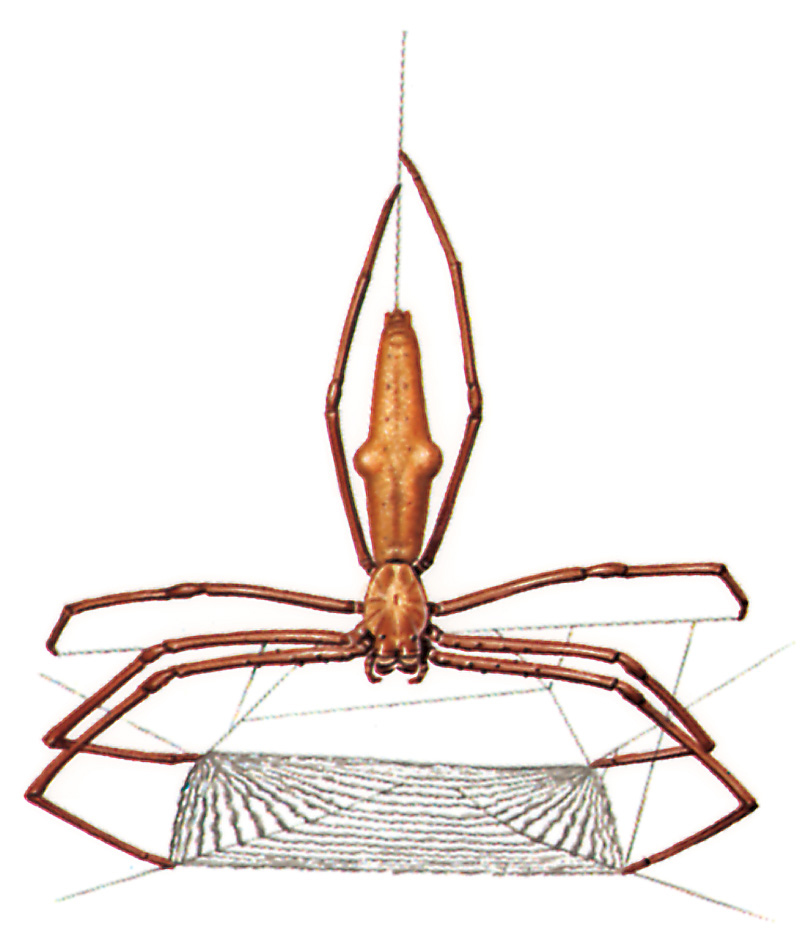

Ogre-faced spiders,

also called net-casting spiders, make webs that consist of a small, sticky mesh supported by a structure of dry silk. The sticky mesh consists mostly of hackled bands. The spider hangs upside down from the dry silk and holds the sticky mesh with its four front legs. When an insect crawls or flies near, the spider stretches the mesh to several times its normal size and sweeps it over the insect.

Funnel weavers

live in large webs that they spin in tall grass, under rocks or logs, or in water. The bottom of the web, in which the spider hides, is shaped like a funnel. The top part of the spider’s web forms a large sheet of silk spread out over the grass, soil, or other surface. When an insect lands on the sheet, the spider runs out of the funnel and pounces on the victim.

Linyphiids,

sometimes called money spiders, weave flat sheets of silk between blades of grass or branches of shrubs or trees. Many of these spiders also spin a mesh of crisscrossed threads above the sheet web. When a flying insect hits the mesh, it falls onto the sheet. Often, an insect will fly directly into the sheet web. The spider, which hangs beneath the web, quickly runs to the insect and pulls it through the webbing. Sheet webs last a long time because the spider repairs any damaged parts.

Scientists typically divide linyphiids into two basic groups, dwarf weavers and sheet-web weavers. The tiny dwarf weavers usually measure less than 1/10 inch (2.5 millimeters) long. Sheet-web weavers generally grow larger and often have patterns on their abdomens.

Orb weavers

build the most beautifully patterned webs of all. They weave their round webs in open areas, often between tree branches or flower stems. Threads of dry silk extend from an orb web’s center like the spokes of a wheel. Coiling lines of sticky silk connect the spokes and serve as an insect trap.

Some orb weavers lie in wait for their prey in the center of the web. Others attach a signal line to the center. These spiders hide in a retreat near the web and hold on to the signal line. When an insect lands in the web, the line vibrates. The spider then darts out and captures the insect. Most orb weavers spin a new web every night. It takes about 30 minutes. Such spiders often eat their old webs to reuse the silk and to consume any tiny insects stuck in the web. Other orb weavers repair or replace damaged parts of their webs.

The bolas spiders spin a single line of silk with a ball of sticky silk at the end. This ball attracts certain kinds of male moths. When the moth flies near, a bolas spider will whirl the line and trap the moth on the sticky ball.

Hunting spiders

Hunting spiders typically creep up on their prey or lie in wait and pounce on it. The strong chelicerae of hunting spiders help them overpower victims. Most seem to locate prey using vibrations transmitted through the ground. A few hunters have large eyes and can see their prey from a distance. Tarantulas have poor vision. They use a system of silk lines radiating from their retreats to both alert them of passing prey and to trip up prey. Some hunting spiders spin simple web nets that stretch out along the ground and stop insects.

Jumping spiders

sneak up and pounce on their prey. These spiders have short legs, but they can jump more than 40 times the length of their bodies. Male jumping spiders rank among the most colorful of all spiders. Thick, colored hairs cover their bodies, especially on their first pair of legs. Jumping spiders possess excellent vision, and the males use their colors to attract females.

Tarantulas

rank as the world’s largest spiders. The biggest ones live in South American jungles. Great numbers of tarantulas also inhabit dry regions of Mexico and the southwestern United States. Many tarantula species dig burrows. A California tarantula builds a turret (small tower) of grass and twigs at the entrance to its burrow. This spider then sits just below the rim and waits for insects to pass within striking distance. A few kinds of tarantulas live in trees. See Tarantula.

Nursery-web spiders,

sometimes called fishing spiders, live near water and hunt aquatic insects, small fish, and tadpoles. These spiders have large bodies and long, thin legs. Because of their light weight, many can walk on water without sinking. They also can dive underwater for short periods. Many females in this group build special webs for their young.

Wolf spiders

thrive in a variety of environments and are excellent hunters. Many kinds have large, hairy bodies, and run swiftly in search of food. Other kinds live near water and resemble fishing spiders in appearance and habits. Still others live in burrows, while some spin funnel-shaped webs. See Wolf spider.

Spiders and people

How spiders help people.

Spiders have helped people for thousands of years by eating harmful insects, including flies, mosquitoes, and such crop pests as aphids and grasshoppers. Spiders rank among the most important predators of these insects.

Scientists believe spider silk and venom will also prove useful to human beings. Spider silk, though extremely fine, has great strength and durability. Biologists study the microscopic structure of this silk to understand its unusual properties. They also study how spiders make the silk by using only a few kinds of proteins dissolved in water. Such studies may help manufacturers develop new ways of producing extremely strong industrial fibers.

Spider venom can affect the human nervous system in many ways, and scientists have learned much about the nervous system by studying the effects of spider venom. Knowledge gained from these studies may lead to cures for illnesses of the nervous system, including Parkinson disease.

Manufacturers also hope to use spider venoms to make new kinds of insecticides. Collectively, the many different spider venoms may contain thousands of compounds that are highly poisonous to insects but harmless to people or other animals.

Dangerous spiders.

Only a few kinds of spiders can inflict bites severe enough to endanger people. The most dangerous spider groups include the recluses and the widows of North America, the redbacks and funnel-web spiders of Australia, and the button spiders of Africa. The bites of these spiders can cause severe pain, but they rarely prove fatal. Moreover, spiders rarely bite people unless seriously threatened.

Spiders in the home.

Many people have a fear of spiders, known as arachnophobia, and do not want spiders in their homes. Web-building spiders often live well hidden indoors and rarely touch floors or walls. As a result, pesticides may not prove effective. A good way to control spiders indoors is to eliminate insects from the home. Spiders will not infest houses in which they can find no food.