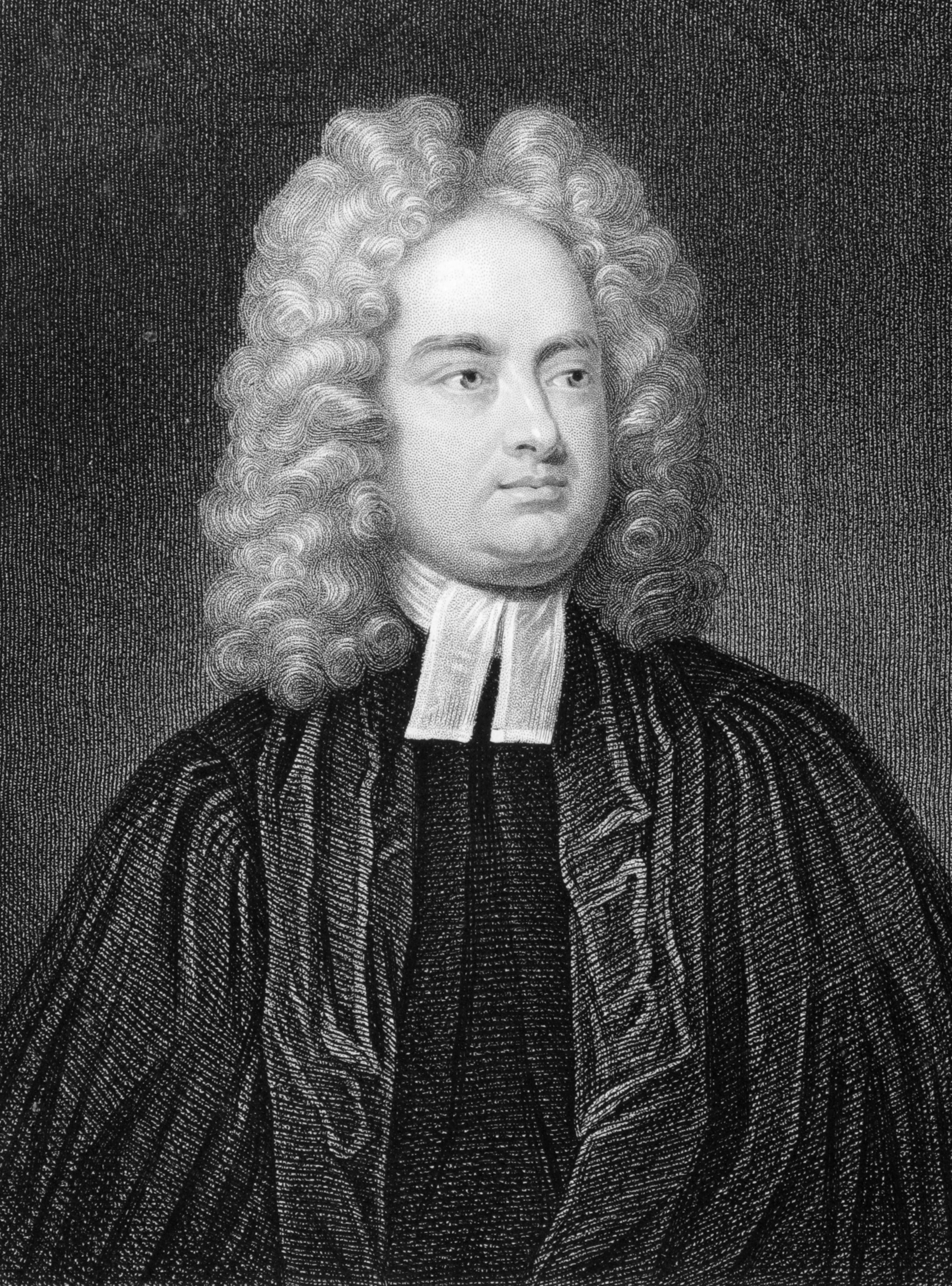

Swift, Jonathan (1667-1745), an English author, wrote Gulliver’s Travels (1726), a masterpiece of comic literature. Swift is called a great satirist because of his ability to ridicule customs, ideas, and actions he considered silly or harmful. His satire is often bitter, but it is also delightfully humorous. Swift was deeply concerned about the welfare and behavior of the people of his time, especially the welfare of the Irish and the behavior of the English toward Ireland. Swift was a Protestant churchman who became a hero in Roman Catholic Ireland.

His life.

Swift was born in Dublin on Nov. 30, 1667. His parents were of English birth. Swift graduated from Trinity College in Dublin, and moved to England in 1688 or 1689. He was secretary to the distinguished statesman Sir William Temple from 1689 until 1699, with some interruptions. In 1695, Swift became a minister in the Anglican Church of Ireland.

While working for Temple, Swift met a young girl named Esther Johnson, whom he called Stella. He and Stella became lifelong friends, and Swift wrote long letters to her during his busiest days. The letters were published after Swift’s death as the Journal to Stella.

Temple died in 1699, and in 1700 Swift became pastor of a small parish in Laracor, Ireland. He visited England often between 1701 and 1710, conducting church business and winning influential friends at the highest levels of government. His skill as a writer became widely known.

In 1710, Swift became a powerful supporter of the new Tory government of Britain. Through his many articles and pamphlets that were written in defense of Tory policies, Swift became one of the most effective behind-the-scenes spokespersons of any British administration.

Queen Anne recognized Swift’s political work in 1713 when she made him dean (head clergyman) of St. Patrick’s Cathedral in Dublin. Swift would have preferred a church position in England. The queen died in 1714, and George I became king. The Whig Party won control of the government that year. These changes ended the political power of Swift and his friends in England.

Swift spent the rest of his life—more than 30 years—as dean of St. Patrick’s. In many ways, these years were disappointing. Swift was disheartened because his political efforts had amounted to so little. He also missed his friends in England, especially the poets Alexander Pope and John Gay. However, he served in Ireland energetically by taking up the cause of the Irish against abuses he saw in British rule. It was as dean that Swift wrote Gulliver’s Travels and the satiric pamphlets that increased his fame, The Drapier’s Letters and A Modest Proposal. Swift’s health declined in his last years and finally his mind failed. He died on Oct. 19, 1745. He left his money to start a hospital for the mentally ill.

Gulliver’s Travels

is often described as a book that children read with delight, but which adults find serious and disturbing. However, even young readers usually recognize that Swift’s “make-believe” world sometimes resembles their own world. Adults recognize that, in spite of the book’s serious themes, it is highly comic.

Gulliver’s Travels describes four voyages that Lemuel Gulliver, who was trained as a ship’s doctor, makes to strange lands. Gulliver first visits the Lilliputians << `lihl` uh PYOO shuhnz >> —tiny people whose bodies and surroundings are only 1/12 the size of normal people and things. The Lilliputians treat Gulliver well at first. Gulliver helps them, but after a time they turn against him and he is happy to escape their land. The story’s events resemble those of Swift’s own political life.

Gulliver’s second voyage takes him to the country of Brobdingnag << BROB dihng nag >> , where the people are 12 times larger than Gulliver and greatly amused by his puny size.

Gulliver’s third voyage takes him to several strange kingdoms. The conduct of the odd people of these countries represents the kinds of foolishness Swift saw in his world. For example, in the academy of Lagado, scholars spend all their time on useless projects such as extracting sunbeams from cucumbers. Here Swift was satirizing impractical scientists and philosophers.

In his last voyage, Gulliver discovers a land ruled by wise and gentle horses called Houyhnhnms << hoo IHN uhmz or HWIHN uhmz >> . Savage, stupid animals called Yahoos also live there. The Yahoos look like human beings. The Houyhnhnms distrust Gulliver because they believe he is a Yahoo. Gulliver wishes to stay in the agreeable company of the Houyhnhnms, but they force him to leave. After Gulliver returns to England, he converses at first only with the horses in his stable.

Some people believe Swift was a misanthrope (hater of humanity), and that the ugliness and stupidity in his book reflect his view of the world. Other people argue that Swift was a devoted and courageous Christian who could not have denied the existence of goodness and hope. Still others claim that in Gulliver’s Travels, Swift is really urging us to avoid the extremes of the boringly perfect Houyhnhnms and the wild Yahoos, and to lead moderate, sensible lives.

Scholars are still trying to discover all the ways in which real people, institutions, and events are represented in Gulliver’s Travels. But readers need not be scholars to find pleasure in the book and to find themselves set to thinking about its distinctive picture of human life.

Swift’s other works.

A Modest Proposal (1729) is probably Swift’s second best-known work. In this essay, Swift pretends to urge that Irish babies be killed, sold, and eaten. They would be as well off, says Swift bitterly, as those Irish who grow up in poverty under British rule. Swift hoped this outrageous suggestion would shock the Irish people into taking sensible steps to improve their condition. He had in mind such steps as the earlier refusal of the Irish to allow the British to arrange for Irish copper coins. The Irish rejected these coins because it was widely believed that the coins would be debased. Swift’s series of Drapier’s Letters (1724) actually forced a change in British policy on this matter.

A Tale of a Tub (1704), on the surface, is a story of three brothers arguing over their father’s last will. But it is actually a clever attack on certain religious beliefs and on humanity’s false pride in its knowledge.

In The Battle of the Books (1704), a lighter work, Swift imagines old and new books in a library waging war on each other. This work reflected a real quarrel between scholars who boasted of being modern and scholars who believed the wisdom of the ancient thinkers could not be bettered.

Swift could be very playful. He loved riddles, jokes, and hoaxes. One of his best literary pranks was the Bickerstaff Papers (1708-1709). In this work, he invented an astrologer named Isaac Bickerstaff to ridicule John Partridge, a popular astrologer and almanac writer of the time. Swift satirized Partridge by publishing his own improbable predictions, including a prediction of Partridge’s own death. Swift then published a notice that Partridge had died, which many people believed.

Swift wrote a great deal of poetry and light verse. Much of his poetry is humorous, and it is often sharply satirical as well. But many of his poems, both comic and serious, show his deep affection for his friends.

Swift’s personality.

Whether Swift hated humanity or whether he mocked people to reform them is still disputed. But there are some things Swift clearly either hated or valued. He hated those who attacked religion, particularly when they pretended to be religious themselves. He also hated the tyranny of one nation over another. Above all, he hated false pride—the tendency of people to exaggerate their accomplishments and overlook their weaknesses. Swift valued liberty, common sense, honesty, and humility. His writings—whether bitter, shocking, or humorous—ask the reader to share these values.