Tunnel is an underground passageway. Tunnels are dug through hills and mountains, and under cities and waterways. They provide highways, subways, and railroads with convenient routes past natural and artificial obstacles. Miners use tunnels to reach valuable minerals deep within the earth. Tunnels also carry large volumes of water for hydroelectric power plants. Some tunnels provide fresh water for irrigation or drinking, and others transport wastes in sewer systems. In addition, tunnels provide underground space for cold storage.

How tunnels are built

People dig some tunnels through rock or soft earth. Other tunnels, called submerged tunnels, lie in trenches dug into the bottoms of rivers or other bodies of water.

Rock tunnels.

The construction of most rock tunnels involves blasting. To blast rock, workers first move a scaffold called a jumbo next to the tunnel face (front). Mounted on the jumbo are several drills, which bore holes into the rock. The holes are usually about 10 feet (3 meters) long, but may be longer or shorter depending on the rock. The holes measure only a few inches or centimeters in diameter. Workers pack explosives into the holes. After these charges are exploded and the fumes sucked out, carts carry away the pieces of rock, called muck.

If the tunnel is strong, solid rock, it may not require extra support for its roof and walls. But most rock tunnels are built through rock that is naturally broken into large blocks or contains pockets of fractured rock. To prevent this fragmented rock from falling, workers usually insert long bolts through the rock or spray it with concrete. Sometimes they apply a steel mesh first to help hold broken rock. Workers using an older method erect rings of steel beams or timbers. In most cases, they add a permanent lining of concrete later.

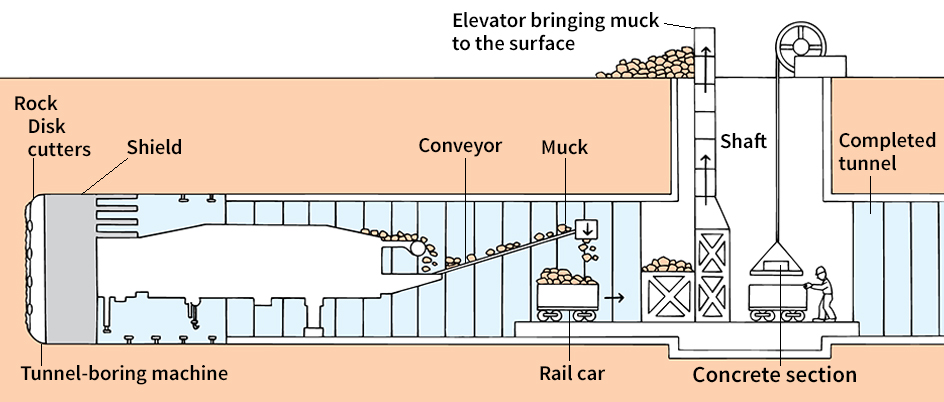

Tunnel-boring machines dig tunnels in soft, but firm rock such as limestone or shale and in hard rock such as granite. A circular plate covered with disk cutters is attached to the front of these machines. As the plate rotates slowly, the disk cutters slice into the rock. Scoops on the machine carry the muck to a conveyor that removes it to the rear. To cut weaker rock such as sandstone, workers use road headers and other machinery.

Earth tunnels

include tunnels that are dug through clay, silt, sand, or gravel, or in muddy riverbeds. Tunneling through such soft earth is especially dangerous because of the threat of cave-ins. In most cases, the roof and walls of a section of tunnel dug through these materials are held up by a steel cylinder called a shield. Workers leave the shield in place while they remove the earth inside it and install a permanent lining of cast iron or precast concrete. After this work is completed, jacks push the shield into the earth ahead of the tunnel, and the process is repeated. Some tunnel-boring machines have a shield attached to them and are able to position sections of concrete tunnel lining into place as they dig. Such a machine dug part of the London subway system.

If the soil is strong enough to stand by itself for at least a few hours, workers may not use concrete sections. Instead, they would hold the soil in place with bolts, steel ribs, and sprayed concrete.

Tunneling through the earth beneath bodies of water adds the danger of flooding to that of cave-ins. Engineers generally prevent water from entering a tunnel during construction by compressing the air in the end of the tunnel where the work is going on. When the air pressure inside the tunnel exceeds the pressure of the water outside, the water is kept out. This method was used to build the subway tunnels under the East River in New York City and the River Thames in London.

Submerged tunnels

are built across the bottoms of rivers, bays, and other bodies of water. Submerged tunnels are generally less expensive to build than those dug by the shield or compressed-air methods. Construction begins by dredging a trench for the tunnel. Closed-ended steel or concrete tunnel sections are then floated over the trench and sunk into place. Next, divers connect the sections and remove the ends, and any water in the tunnel is pumped out. In most cases, the tunnels are then covered with earth. Submerged tunnels include the railroad tunnel under the Detroit River and the rapid transit tunnel under San Francisco Bay.

Kinds of tunnels

There are four main types of tunnels. They are: (1) railroad tunnels, (2) motor-traffic tunnels, (3) water tunnels, and (4) mine tunnels.

Railroad tunnels.

Among the world’s greatest engineering feats was the boring of long railroad tunnels through the rocks of the Alps and the Rocky Mountains. Railroad tunnels reduce traveling time and increase the efficiency of trains. The steeper a locomotive must climb, the less weight it can pull. Tunnels through mountains reduce steep grades, allowing trains to haul more goods and people.

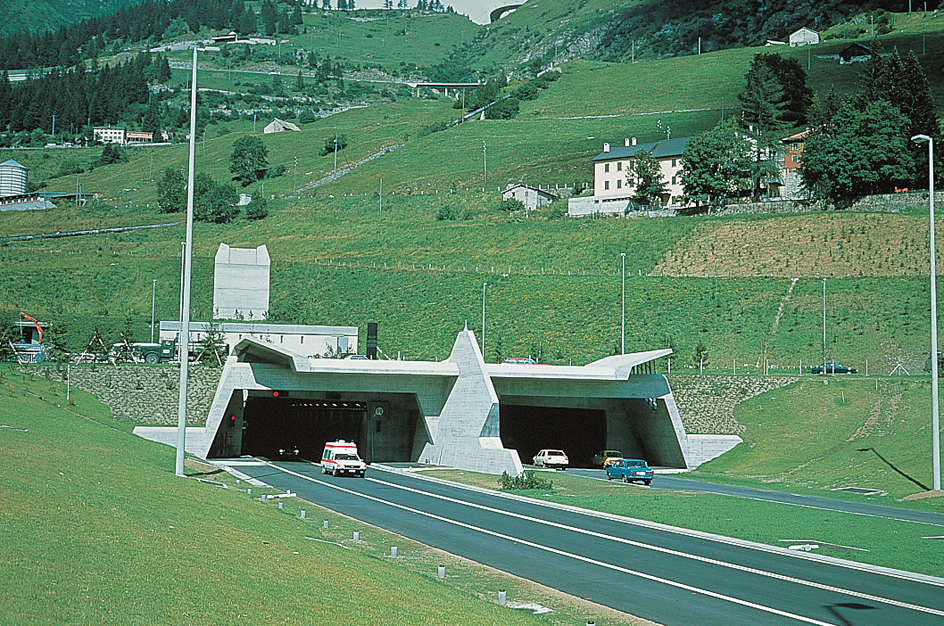

Motor-traffic tunnels

provide routes for automobiles, trucks, and other motor vehicles. Such tunnels have special equipment to remove exhaust fumes. For example, the Holland Tunnel, which is under the Hudson River and which links New York City and New Jersey, uses electric fans for ventilation. These fans are capable of completely changing the air in the tunnel every 90 seconds. Many motor-traffic tunnels also have signal lights and special monitoring systems to help prevent traffic jams.

Water tunnels.

Many tunnels provide water to city waterworks, to hydroelectric power plants, or to farms for irrigation. Others carry storm drainage or sewage. Most water tunnels measure 10 to 20 feet (3 to 6 meters) or more in diameter, and they have smooth linings that help the water flow. Many tunnels carrying water to hydroelectric power plants are lined with steel to withstand extremely high water pressures.

Mine tunnels

are made by blasting or by tunneling machines. Mine shafts are not usually lined, but they may have supports.

History

In Africa, there is evidence of mines created tens of thousands of years ago with tools made of deer antlers and horse bones. Prehistoric people in Europe used similar tools to mine flint. The Egyptians may have been the first to fracture rock at a tunnel face by building fires in front of the face and then pouring water on it. The Egyptians built tunnels to mine metals and store water, and as approaches to tombs.

In the A.D. 1600’s, people began to use gunpowder to blast through hard rock. The rise of railroads during the 1800’s caused a sharp increase in tunnel building and stimulated the invention of tunnel-building devices. In 1825, workers used a tunnel shield to build a railroad tunnel under the River Thames in London. This tunnel, completed in 1843, was the first tunnel built under a navigable river. The 91/3-mile (15-kilometer) St. Gotthard railroad tunnel, dug through the Swiss Alps between 1872 and 1882, was the first major tunnel built using dynamite and a jumbo. In the early 1900’s, tunnel building speeded up with the invention of faster and lighter drills, harder drill bits, and mechanical muck loaders.

In 1882, the British used the first tunnel-boring machine to begin to drill a tunnel under the English Channel. This machine dug at a rate of about 50 feet (15 meters) in a day. Today, many boring machines are more than 10 times as fast as that. The United Kingdom stopped work on the channel tunnel after about 8,000 feet (2,400 meters) of material had been drilled. The British feared that foreign armies could use the tunnel to invade the United Kingdom.

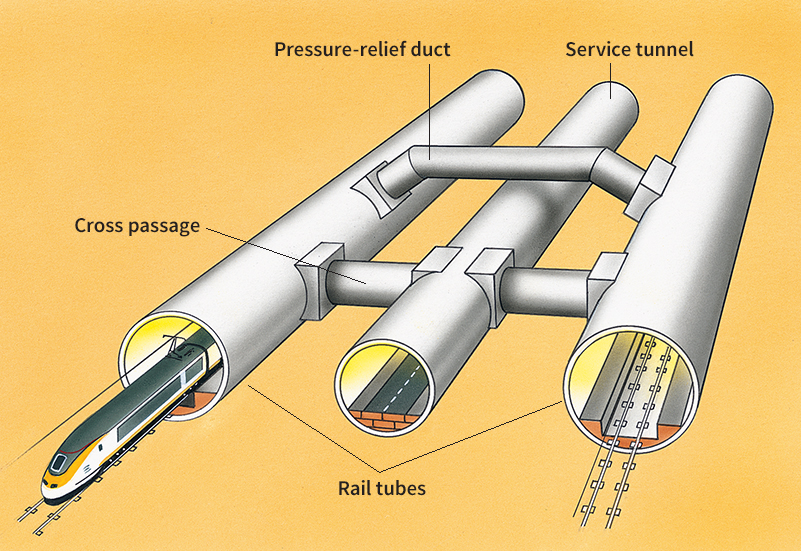

In 1987, work began once more on a tunnel under the English Channel. Workers used huge boring machines, each longer than two football fields. The tunnel was completed in 1994. It consists of two railway tubes connected to a small tube for service and maintenance vehicles. Three kinds of trains can use the tunnel: (1) freight trains, (2) high-speed passenger trains, and (3) shuttle trains for passengers and their automobiles.

The longest underwater tunnel, Japan’s Seikan Tunnel, opened in 1988. This railroad tunnel stretches 331/2 miles (53.9 kilometers) under the Tsugaru Strait between Honshu and Hokkaido islands. The longest highway tunnel, Norway’s Laerdal Tunnel, opened in 2000. It extends 15.2 miles (24.5 kilometers) under the Jotunheimen mountain range in southern Norway. The longest railroad tunnel is Switzerland’s Gotthard Base Tunnel, completed in 2016. It runs under the Swiss Alps for 35 miles (57 kilometers).