Turtle is a four-legged, smooth-skinned or scaly animal whose body is protected by a sturdy, round shell. Most turtles can pull their head, legs, and tail into their shell when threatened. Few other vertebrates (backboned animals) have such tough natural armor.

Turtles are cold-blooded—that is, their body stays about the same temperature as the surrounding air or water. Cold temperatures prevent turtles from becoming warm and active, so turtles cannot live in regions that remain cold throughout the year. Turtles live almost everywhere else, including deserts, forests, grasslands, lakes, marshes, ponds, rivers, and seas.

About 300 species of turtles exist. Some turtles live only on land. Others spend almost their entire life in the sea. Still others dwell mainly in fresh water or spend about equal time on land and in fresh water. Turtles often live their whole life within a few miles or kilometers of where they hatched. But many sea turtles migrate thousands of miles or kilometers from their birthplace.

Turtles vary greatly in size. The largest turtle species, the sea-dwelling leatherback turtle, grows from 4 to 8 feet (1.2 to 2.4 meters) long and weighs up to 2,000 pounds (900 kilograms). But the common bog turtle of the eastern United States measures only about 4 inches (10 centimeters) and weighs about 4 ounces (110 grams).

Sea turtles, which swim rapidly, rank as the fastest turtles. One species, the green sea turtle, can swim for brief periods at a speed of nearly 20 miles (32 kilometers) per hour. On land, many turtles move slowly and heavily. But some land turtles walk with surprising speed.

The first turtles arose more than 200 million years ago. The best-known early turtle, Proganochelys, lived during the time of the dinosaurs. Archelon, a sea turtle of around 70 million years ago, grew about 12 feet (3.7 meters) long. These creatures went extinct, probably as a result of natural disasters and changes in their environment. See Archelon.

Today, many species of turtles face extinction as a result of human activity. People hunt turtles for food or for their shells, and they gather turtle eggs. The building of cities, suburbs, and farms destroys areas where turtles live. Some people catch or raise turtles to keep as pets. This article will discuss the body of turtles, the life of turtles, kinds of turtles, and how human activities affect these animals.

The body of a turtle

Different turtle species have bodies adapted to different environments. All turtles have a shell that covers the entire body except for the head, legs, and tail. Highly developed sensory organs help turtles find food, spot predators (preying animals), and identify other turtles.

Shell.

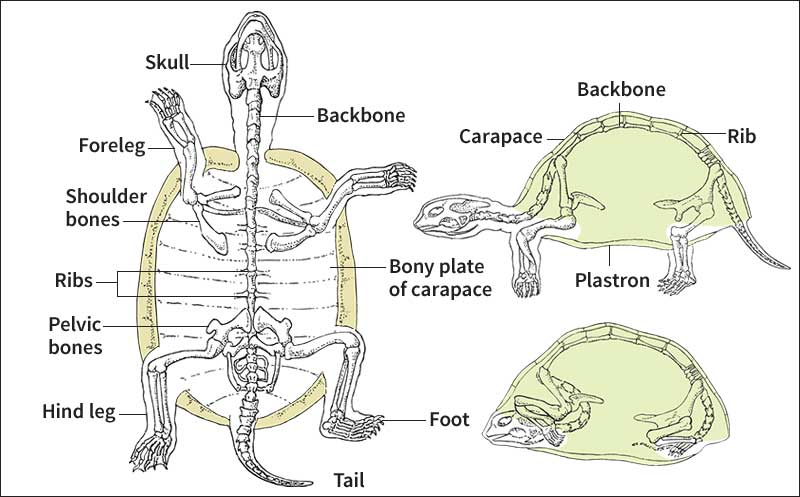

A turtle’s shell consists of living tissue. A damaged shell can heal like other tissue but may never regain its original appearance. The shell has two layers. Bony plates form the inner layer, which is actually part of the skeleton. Among most species, hard, horny structures called scutes compose the outer layer. Scutes develop from skin tissue. Soft-shelled turtles and the leatherback turtle have an outer layer of tough skin rather than scutes.

The shell consists of two major pieces: (1) the carapace, which covers the back, and (2) the plastron, which covers the belly. A bony structure called the bridge joins the carapace and the plastron along each side of the body. Most turtles that live on land have a high, domed shell. Those that live in water have a flatter, more streamlined shell. Some species, including Blanding’s turtles, box turtles, and mud turtles, have a hinged plastron. They can close it tightly against the carapace after withdrawing completely into their shell.

Some turtle shells are plain black, brown, or dark green. However, other shells have bright green, orange, red, or yellow markings. The plastron of most turtles has a lighter color than the carapace. In many species, striking patterns decorate the plastron.

Head.

Most turtles have hard scales, smooth skin, or a combination of both covering their head. Skin also covers the turtle’s ear canals.

Some ancient turtles had rows of small teeth on the roof of their mouth. But modern turtles have no teeth. They depend on a hard, sharp-edged beak to cut food. Many turtles have powerful jaws to tear food and capture prey. The jaws of some turtles can even crush hard seeds or the shells of snails and mussels.

Legs and feet

vary according to turtles’ natural habitat. Land turtles, particularly tortoises, have heavy, short, clublike legs and feet. Most freshwater turtles have longer legs and webbed feet. Sea turtles have front legs shaped like paddles, with flippers instead of feet.

A turtle’s hip and shoulder bones, unlike those of any other animal, sit inside the ribcage. The ribcage forms part of the shell. This arrangement enables most kinds of turtles to pull their legs inside their shell. In some turtle species, the shell is too small to accommodate the legs. In a few others, the structure of the hip and shoulder bones prevents the turtle from retracting its legs.

Senses.

Turtles have well-developed senses of sight and touch. They typically have good color vision, which assists them in searching for food, avoiding predators, and recognizing other members of their own species. Scientific experiments indicate that turtles also have a good sense of smell, at least for nearby objects. Many display preferences for certain foods while rejecting others, indicating a developed sense of taste. Turtles can hear low-pitched sounds about as well as people can.

The life of a turtle

Turtles hatch from eggs and receive no parental care. Most of a turtle’s growth occurs during its first 5 to 10 years. The turtle continues to grow after this time, but at a much slower rate. Scientists think turtles live longer than any other vertebrates, including people. Some box turtles may live more than 100 years, and some tortoises more than 150 years.

Reproduction.

Turtle eggs become fertilized inside the female’s body. One mating can result in the fertilization of all the eggs a female lays for several years. Most species lay their eggs between late spring and late autumn, and some lay eggs more than once during this period. Green sea turtles, for example, usually lay about three clutches (sets) of eggs in one breeding season.

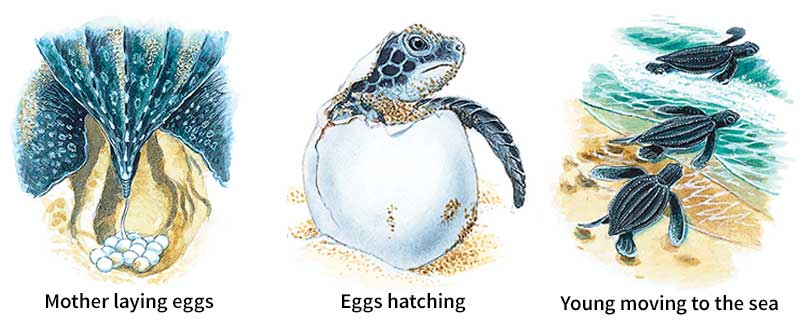

All turtles lay their eggs on land. Among most species, the female digs a hole in the ground with her back feet when ready to lay her eggs. She lays the eggs in the hole and covers them with soil, sand, or rotting plant matter. The number of eggs varies. An African pancake tortoise lays only one egg per clutch, but a sea turtle may lay as many as 200 eggs at a time. With few exceptions, the female turtle leaves after covering her eggs and does not return.

Turtle eggs require an external source of heat for incubation—that is, to maintain the proper temperature to develop and hatch. The heat usually comes from the sun, although some forest turtles use heat from decaying vegetation to help incubate their eggs. In sunny climates, turtles often build their nests near vegetation or other sources of shade to keep the eggs from overheating. In most species of turtle, the incubation temperature determines the sex of the hatchlings. Warmer temperatures tend to produce females in many species, while cooler temperatures produce males. In other species, intermediate temperatures result in males, with females resulting from both warmer and cooler temperatures.

Young.

Newly hatched turtles must dig their way to the surface of the ground, obtain food, and protect themselves, all without assistance. Many animals prey on turtle eggs and baby turtles. Predators flock to beaches to eat newly hatched sea turtles as they crawl toward the water. Fish attack many of them as they enter the sea. Skunks, raccoons, and snakes dig up the nests of freshwater and land turtles and eat the eggs.

Food.

Most turtles are omnivores—that is, they eat a mixture of animals and plants. Food preferences vary among different turtle species and often depend on the type of food available. Some species, such as the green sea turtle and many kinds of tortoises, feed almost entirely on plants. Other species, including the giant leatherback and the loggerhead, eat chiefly animals.

In some turtle species, the sexes have different feeding habits. Female map turtles crush hard-shelled clams, snails, and other animals for food, while the males eat softer invertebrates (animals without backbones). Scientists believe this specialization in feeding may help keep the sexes from competing for limited food resources.

Hibernation.

Turtles, like other cold-blooded animals, must hibernate during periods of cold weather. Most freshwater turtles hibernate by burrowing into the warm, muddy bottom of a pond, stream, or other body of water. Land turtles bury themselves in soil or under rotting vegetation.

Some turtles survive hot, dry periods in a state of limited activity called estivation. During estivation, the turtle neither feeds nor moves.

Kinds of turtles

Zoologists generally recognize 13 or 14 families of turtles that exist today. Most families belong to one of seven main groups: (1) mud and musk turtles, (2) pond, box, and water turtles, (3) sea turtles, (4) side-necked turtles, (5) snapping turtles, (6) soft-shelled turtles, and (7) tortoises.

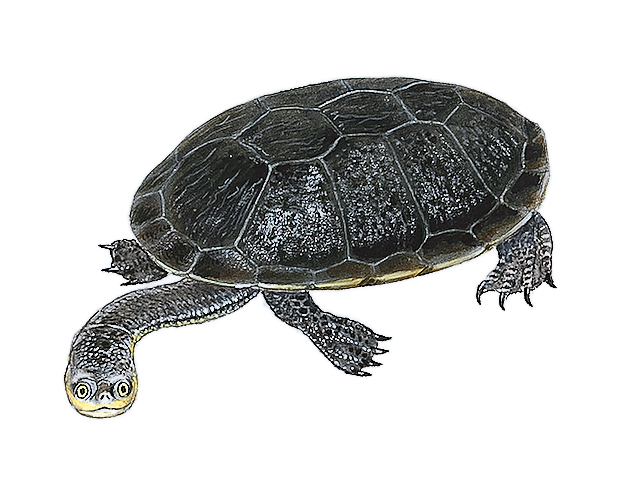

Mud and musk turtles

release musk (a foul-smelling substance) from glands on the bridge in front of their hind legs when disturbed. They make up the family Kinosternidae, which includes about 25 freshwater species. They live in the Western Hemisphere, particularly in Central America and the United States.

Few mud and musk turtles grow more than 6 inches (15 centimeters) long, though some tropical species reach twice that size. All of these turtles have large heads and strong jaws, and larger species will bite if handled. Mud and musk turtles of the United States include the common mud turtle, common musk turtle, razor-backed musk turtle, and yellow mud turtle. People often call the common musk turtle the “stinkpot” because its musk has a particularly strong, unpleasant smell.

Pond, box, and water turtles

live partly or mostly in water, including lakes, ponds, rivers, streams, and tidewater areas. A few species, including box turtles and wood turtles, dwell mainly on land. Most are omnivores, but some eat mainly animals or mainly plants. Scientists once grouped all such turtles into a single family. They now classify New World and Old World groups as distinct families based on genetic (hereditary) differences and certain differences in body structure.

New World pond, box, and water turtles make up the family Emydidae, which includes about 40 species. Members of this family live in North and South America, with one wide-ranging species also found in Europe, western Asia, and northern Africa. Pond, box, and water turtles of North America include the box turtles, chicken turtle, diamondback terrapin, map turtles, painted turtle, red-eared turtle, spotted turtle, and wood turtles. Many species have bright coloring, with green, red, or yellow markings on their head, legs, and shell. Most pond, box, and water turtles of the United States are small, but some may grow more than 1 foot (30 centimeters) long.

Old World pond, box, and water turtles form the largest family of turtles, Bataguridae, also known as Geomydidae. This family includes roughly 60 species found in Europe and Asia and about 10 species of Central and South American wood turtles. These turtles look and act much like New World varieties. People regard the meat of many Asian species as a delicacy, severely threatening their survival.

Sea turtles

spend most or all of their lives in the sea. Six species have bony shells covered with scutes. They are: (1) the green sea turtle, (2) the flatback, (3) the hawksbill, (4) the loggerhead, (5) the Kemp’s ridley, also known as the Atlantic ridley, and (6) the olive ridley or Pacific ridley. Most zoologists classify these species into one family, Cheloniidae. A seventh species, the leatherback, forms its own family, Dermochelyidae. Its shell has far fewer bones than that of the other sea turtles. The shell is covered in thick, leathery skin, rather than scutes. Most sea turtles live in warm seas throughout the world. The leatherback often ventures into cold Canadian waters. Only the Australian flatback does not appear in the coastal waters of the United States.

Sea turtles include the largest turtle species. Even the smallest ones, the ridleys, reach 28 inches (70 centimeters) long and weigh nearly 100 pounds (45 kilograms).

Sea turtles swim by beating their flippers much as a bird flaps its wings. Other turtles, by contrast, swim with a back-and-forth paddling motion. Sea turtles cannot withdraw into their shell, so they depend on their size and fast swimming for defense.

Female sea turtles do not normally leave the water, except to lay their eggs. Most of the males never return to land after entering the sea as hatchlings. The females often migrate thousands of miles or kilometers to reach their breeding beaches. They drag themselves onto a sandy beach, bury their eggs, and then return to the sea. While on land, the females are nearly helpless.

Side-necked turtles

bend their neck sideways when withdrawing their head, instead of pulling it straight back into their shell like other turtles. Scientists typically divide this large group of about 75 species into three families: (1) Chelidae, (2) Pelomedusidae, and (3) Podocnemididae. Side-necked turtles live in Africa, Australia, and South America. They live mostly in water and typically move rather clumsily on land. Most of these turtles breathe by extending their long neck and head to the water’s surface. However, at least one Australian species can breathe underwater by using gill-like structures in its cloaca, the opening through which wastes leave the turtle’s body.

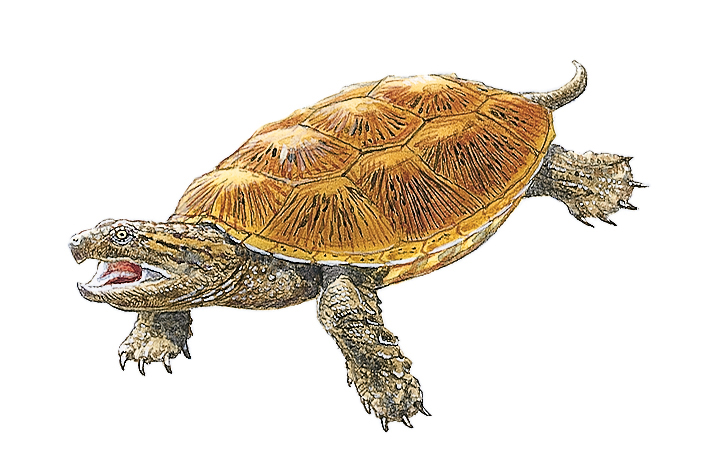

Snapping turtles

are large freshwater turtles in the Americas with a big head and strong jaws. According to most scientists, they compose the family Chelydridae. Traditionally, scientists recognize two species of snapping turtle. One species, the common snapping turtle, lives from Canada to Ecuador and grows up to 19 inches (47 centimeters) long. The other species, the alligator snapping turtle, lives in the south-central and southeastern United States. Alligator snapping turtles rank among the world’s largest and heaviest freshwater turtles. Males may measure more than 30 inches (76 centimeters) long and weigh over 200 pounds (91 kilograms).

Snapping turtles eat a wide variety of food, including fish, frogs, insects, mussels, and waterfowl. They also feed on plants and algae (simple plantlike organisms). A snapper’s small shell does not provide much protection, so it depends on its sharp-edged beak for defense. Snappers may bite fiercely if disturbed.

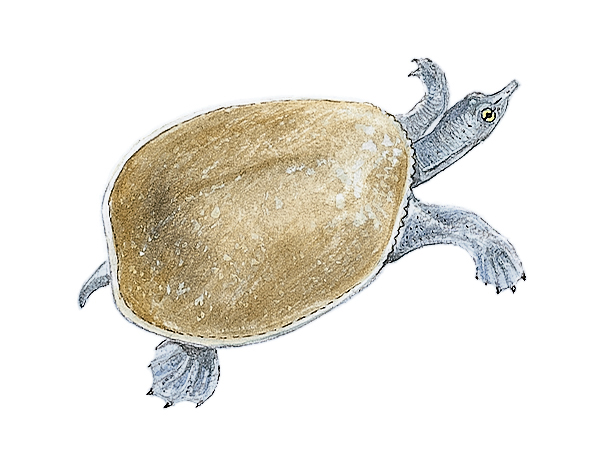

Soft-shelled turtles

have shells covered in smooth skin, rather than scutes. These primarily freshwater turtles make up the family Trionychidae, which includes about 25 to 30 species. They live in Africa, Asia, and North America. Three species—the smooth softshell, the spiny softshell, and the Florida softshell—live in the continental United States. Two species of Chinese softshells have become established in Hawaii.

Unlike other turtles, softshells have fleshy lips that cover their beak. Most also have a long, tube-shaped nose that they push above the water’s surface to breathe. Most softshells do not grow much longer than 1 foot (30 centimeters), but some species measure up to 3 feet (90 centimeters) long. They typically feed on animal matter, especially fish and invertebrates, and may bite viciously and quickly if disturbed.

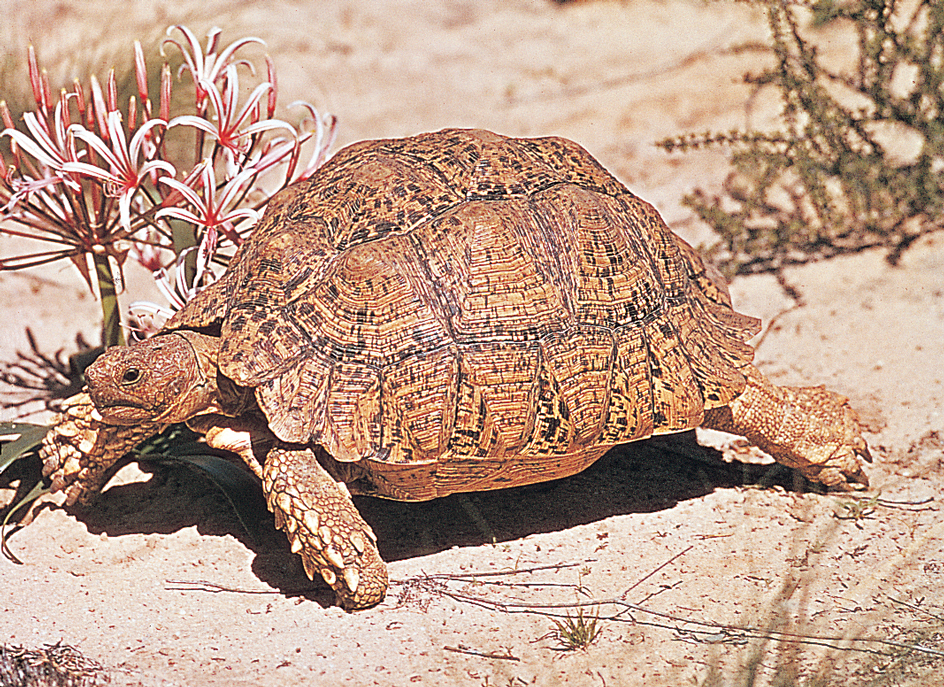

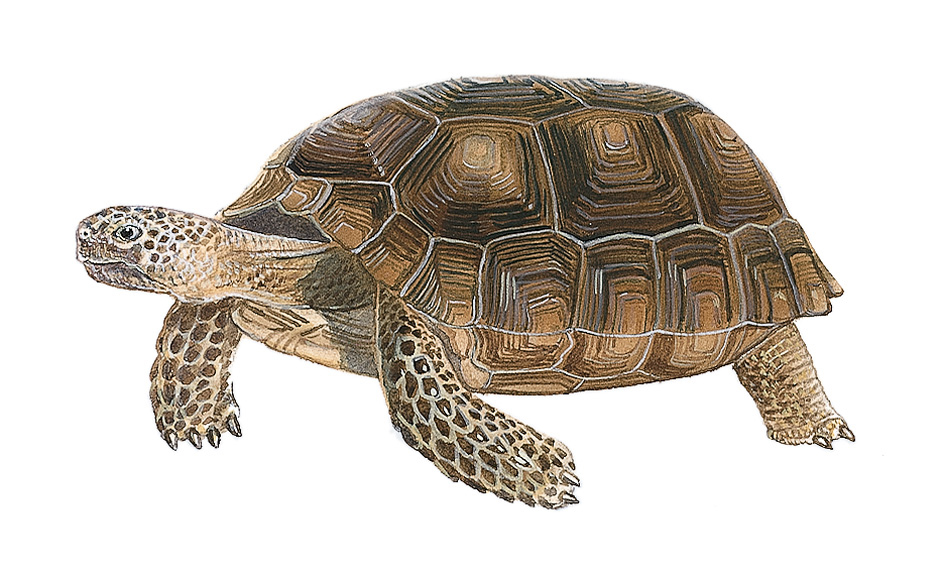

Tortoises

live only on land. They form a family of about 50 species called Testudinidae. Tortoises live in Africa, Asia, Europe, North and South America, and on certain islands in the oceans. The world’s largest tortoises inhabit the Aldabra Islands in the Indian Ocean and the Galapagos Islands in the Pacific Ocean. Some Galapagos tortoises have been known to grow to 6 feet (1.8 meters) long and weigh over 700 pounds (320 kilograms).

The desert tortoise makes its home in the dry areas of the southwestern United States. The gopher tortoise of the southeastern United States lives in long burrows that it digs with its broad front legs. The burrows average about 25 feet (8 meters) long and reach about 6 feet (2 meters) deep. The yellow-footed and red-footed tortoises inhabit the rain forests of South America.

Most tortoises move slowly and have a high, domed shell. However, the African pancake tortoise has a flat, flexible shell. When in danger, this tortoise runs quickly into a crack between rocks. It then takes a deep breath and inflates its body to wedge itself tightly in the crack.

Most tortoises feed almost entirely on plants. Some species eat cactuses, not deterred by the spines. Gopher tortoises—and probably other species—occasionally eat animal waste or the remains of dead animals, perhaps to obtain minerals lacking in their usual diet.

Other kinds of turtles.

The remaining families of turtles each consist of a single living freshwater species. They are the pig-nosed turtle of Australia and New Guinea (family Carettochelyidae); the Central American river turtle (family Dermatemydidae); and Southeast Asia’s big-headed turtle (family Platysternidae). Some scientists place this last turtle in the snapping turtle family.

Turtles and human beings

Human activities present a serious threat to the survival of many turtles. Wildlife experts classify more than 40 kinds of turtles as endangered. These turtles include many types of tortoises and most sea turtles.

People have long used turtle meat and eggs for food and turtle shells as ornaments. The most threatened species of turtles include those most valued for these products. For example, people in many parts of the world eat green sea turtles. The hunting of adults and taking of eggs has seriously endangered its survival. The hawksbill turtle also has become nearly extinct. People use tortoise shell, a substance from its carapace, to make ornamental objects. Other sea turtles, especially the leatherback and Kemp’s ridley, also risk extinction because they can drown after accidentally becoming entangled in commercial fishing nets and lines.

People further endanger turtles by polluting waters. Storm-water runoff from lawns, streets, and farmland carries dangerous chemicals into bodies of water. It also adds excess nitrogen and phosphorus to ponds and streams where turtles live. These chemicals stimulate a process called eutrophication that can harm animals living in the water (see Eutrophication).

Some governments have laws that prohibit the capture of rare species of turtles. Conservationists have established turtle preserves in certain areas, and scientists are experimenting with raising valuable species on turtle farms. But zoologists must learn more about turtles in the wild to save many of the endangered species.

Pet shops throughout the United States once sold millions of painted turtles and red-eared turtles each year. But medical researchers discovered that many of these turtles carried Salmonella bacteria, which cause a serious illness in human beings. In 1975, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration banned the sale of many pet turtles. Other countries have passed similar laws restricting trade in pet turtles. However, people still sell thousands of baby turtles each year. These turtles can also cause problems for native species when people release them into the wild.