Versailles, << vehr SY, >> Treaty of, officially ended military actions against Germany in World War I. The treaty was signed at the Palace of Versailles, near Paris, on June 28, 1919, and went into effect on Jan. 10, 1920. Actual combat had ended when Germany accepted an armistice on Nov. 11, 1918.

The treaty provided an official peace between Germany and nearly all the 32 victorious Allied and associated nations, including France, Italy, Japan, and the United Kingdom. China never signed the treaty. The United States would make a separate peace with Germany in 1921 because the U.S. Senate did not ratify the treaty.

The treaty provided a reorganization of the boundaries and certain territories of European nations and areas they controlled in Africa, Asia, and Pacific Ocean islands. It also created several new international organizations, including the League of Nations and the Permanent Court of International Justice. In addition, the treaty provided a system for administering the former colonies of the defeated countries.

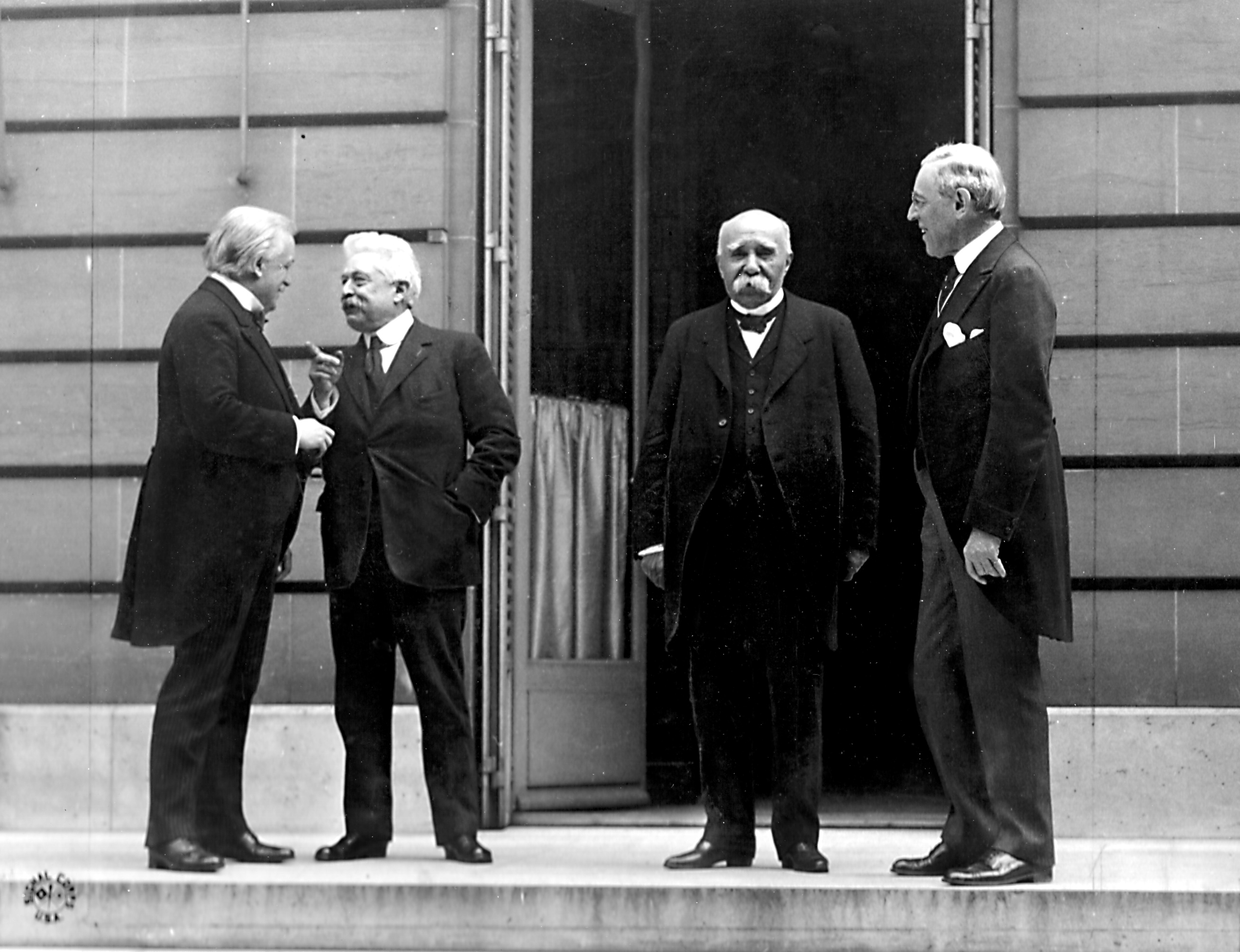

United States President Woodrow Wilson, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Premier Georges Clemenceau, and Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando played the main roles in drafting the treaty. These men were called the Big Four. Orlando temporarily left the conference in protest when the Allies refused Italy’s claims to the port of Fiume in Yugoslavia and to former Austrian territories.

Background of the treaty.

Preparations for peace began well before the armistice. Beginning in 1915, a number of the Allied governments, including Italy and Japan, adopted secret treaties intended to divide among them certain parts of Germany, the Ottoman Empire (now Turkey), and other enemies in the war. German colonial territories in Africa, Asia, and the Pacific Ocean also were to be annexed. Italy joined the Allied war effort as a result of such promises.

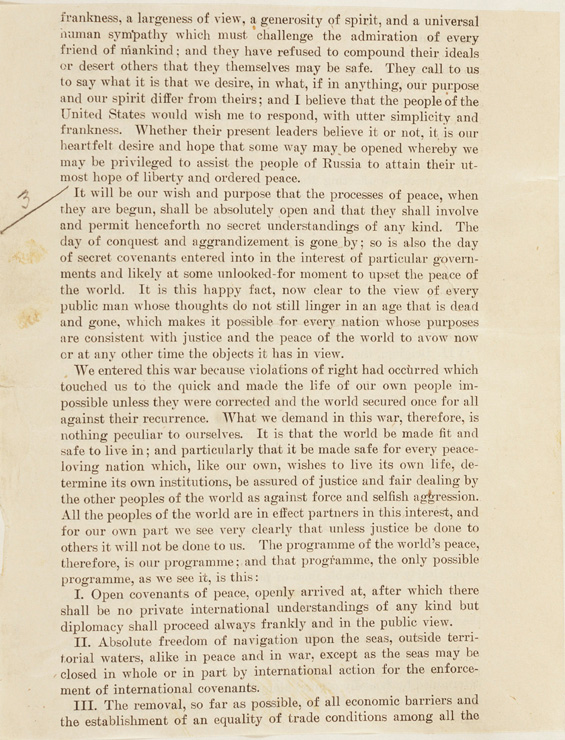

President Wilson presented his ideas for peace in his famous Fourteen Points address on Jan. 8, 1918. He opposed carrying out terms of any secret treaties. He hoped to apply the principle of ethnic self-determination, under which no ethnic group would have to be governed by a nation or state that it opposed. Wilson also called for moderate punishment, both economic and territorial, for Germany. He believed this approach would encourage Germany to establish a democratic government, to help rebuild Europe, and to refrain from waging war in the future out of bitterness. See World War I (The Paris Peace Conference) .

Wilson’s chief goal was to have the treaty provide for the formation of a League of Nations (see League of Nations ). He hoped that the threat of economic or military punishment from League members, including Germany, would prevent future wars.

The other major Allies, however, had little interest in honoring either Wilson’s Fourteen Points or all his goals for the League of Nations. Clemenceau sought to cripple Germany economically, militarily, and territorially. He also sought additional security against any future German aggression through creation of special military alliances with Britain and the United States. Lloyd George wanted to leave Germany with enough resources for trade but not enough for waging war. Other Allies, especially Italy and Japan, were chiefly concerned with obtaining more land.

Provisions.

At the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, representatives of the 32 Allied nations met to draw up terms of peace with Germany and its allies. German representatives were not allowed to take part. The main provisions of the treaty set up the League of Nations, revised boundaries, disarmed Germany, and called for reparations. Reparations consisted of money and other resources Germany would have to give the Allies for severe losses they suffered in the war.

To win support for certain changes concerning the League of Nations, Wilson compromised on the ideals he had set forth in the Fourteen Points. For example, he accepted terms made in secret treaties. Thus, Italy received the South Tyrol region of Austria-Hungary, and Japan obtained German colonies in the North Pacific Ocean and German holdings in China’s Shandong province. Wilson also compromised on reparations, agreeing to much more than Germany could afford. Germany had to give the Allies coal, livestock, ships, timber, and other resources, plus cash payments.

Germany lost all its overseas colonies. From its homeland, Germany lost the provinces of Alsace and Lorraine to France; small areas of Eupen, Malmedy, Moresnet, and St. Vith to Belgium; and another border area near Troppau (now Opava) to Czechoslovakia. As a result of a plebiscite (popular vote), Germany also lost Northern Schleswig to Denmark. France gained possession of the coal mines in Germany’s Saar region for 15 years. Danzig (now Gdansk, Poland) was taken from Germany and became a “free city” under protection of the League of Nations. Poland gained most of West Prussia and much of the province of Posen (now Poznan). Germany’s Rhineland was to be demilitarized. But the Allies were to occupy parts of it for 15 years. See Europe (Europe between the world wars) .

Ratification.

In early May 1919, the treaty was presented to Germany. German officials strongly objected, but they had to accept the terms and sign the treaty. The treaty was ratified by Germany’s new republican government and all the major Allied powers except China and the United States. It took effect early in 1920.

Strong opposition to the treaty developed in the United States. Many Americans disagreed with Wilson’s generous approach to the war-torn nations of Europe. Republicans particularly objected to U.S. commitments to the League of Nations. In March 1920, the U.S. Senate refused to approve the treaty. The United States never joined the League of Nations or the Permanent Court of International Justice. In August 1921, however, Germany and the United States concluded a separate peace in the Treaty of Berlin.

Effects.

The lost land and huge reparations greatly angered many Germans, who also felt bitter about a “war guilt” clause in the treaty that declared Germany solely responsible for the war. These factors, aggravated by poor economic conditions in the 1930’s, may have contributed to the rise of German dictator Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party during the 1930’s.

See also World War I (The peace settlement) ; World War II (The Peace of Paris) .