Webster, Daniel (1782-1852), was the best-known American orator, and one of the ablest lawyers and statesmen of his time. He gained his greatest fame as the champion of a strong national government. For years after his death, students memorized thrilling lines from his speeches. Such words as “Liberty and Union, now and forever, one and inseparable!” inspired many Northern soldiers during the American Civil War.

Early career.

Webster was born on Jan. 18, 1782, in Salisbury (now Franklin), New Hampshire, and was graduated from Dartmouth College. He studied law in Boston, and then became a successful lawyer in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. At the beginning of his career, Webster did not favor a strong national government. Instead, he stood for the rights of the states.

Portsmouth was a thriving seaport until President Thomas Jefferson’s embargo and the War of 1812 destroyed most of its overseas trade. Siding with the local shipowners, Webster opposed trade restrictions and war. As a Federalist in the United States House of Representatives from 1813 to 1817, he objected to war taxes, and helped defeat a bill for drafting soldiers. He said that state governments should “interpose” to protect their citizens from the national government.

Webster moved to Boston in 1816. New spinning and weaving mills were springing up along New England streams where there was water power. In much of the Northeast, manufacturing came to be more important than shipping. The manufacturers desired a strong national government that could aid business.

As a friend and attorney of northeastern businessmen, Webster changed his views on national power and states’ rights. In the Dartmouth College case, he argued against New Hampshire’s claim to control the college and won the verdict of the Supreme Court of the United States (see Dartmouth College case ). In another famous case, he held that it was constitutional for the federal government to charter a national bank. Representing Massachusetts in the United States House of Representatives from 1823 to 1827, he insisted that a protective tariff was unconstitutional. But after his election to the United States Senate in 1827, he became the country’s most eloquent tariff advocate.

The U.S. senator.

The so-called “tariff of abominations,” passed in 1828, led John C. Calhoun of South Carolina to develop the theory that a state could “nullify” federal laws, and refuse to obey them (see Nullification ). Senator Robert Y. Hayne of South Carolina brilliantly defended nullification in 1830, and Webster answered him with a famous speech declaring that the Constitution had created a single, unified nation (see Hayne, Robert Young ). In 1832, when South Carolina tried to put nullification into effect, Webster gave strong support to President Andrew Jackson in resisting the attempt.

But Webster disagreed with Jackson on other issues, especially on the question of the Bank of the United States. When Jackson vetoed a bill for rechartering the bank, Webster did his best to save the institution, but failed (see Bank of the United States ).

During his last years in the Senate, Webster opposed adding Texas to the Union, and also opposed the war with Mexico. He feared that the country might break up because of a quarrel over territories in the West. Most Northerners wished to keep slavery from spreading into the new territories, but Southerners were ready to leave the Union if the spread of slavery was prevented. In a “Union-saving” speech, Webster favored the Compromise of 1850, and helped get it passed (see Compromise of 1850 ). Some Northerners denounced him because he was willing to give Southerners part of what they wanted.

Secretary of state.

Webster served as secretary of state under Presidents William Henry Harrison and John Tyler, and then under President Millard Fillmore. Under Tyler, he negotiated the Webster-Ashburton Treaty which settled the Maine boundary dispute and avoided a war with Britain (see Webster-Ashburton Treaty ). Under Fillmore, he befriended the Hungarian patriot Lajos Kossuth and spoke for Hungarian independence (see Kossuth, Lajos ).

The man.

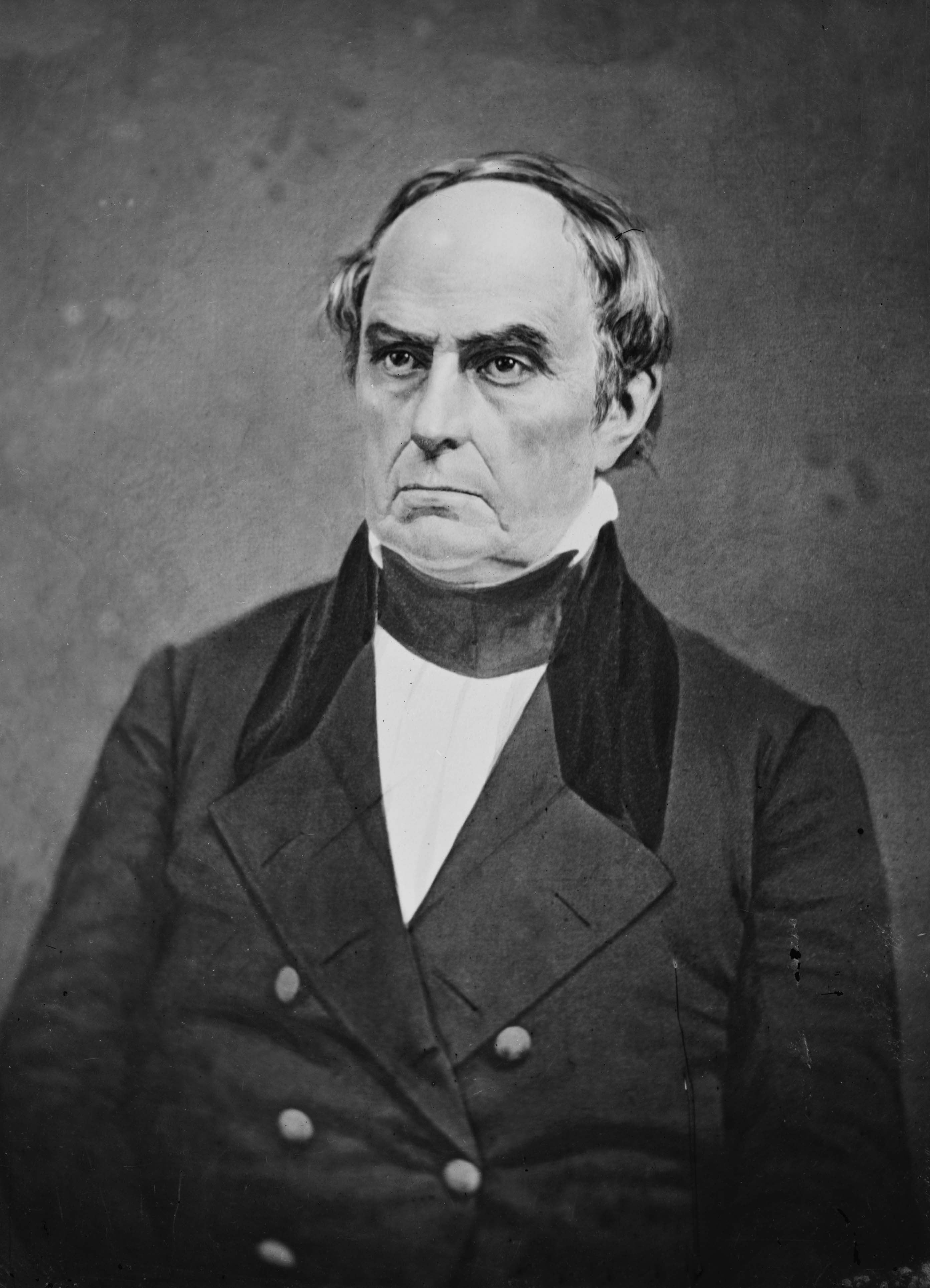

Webster was a handsome, imposing man with deep-set, penetrating eyes, craggy brows, dark complexion, and a rich voice. After the founding of the Whig Party in the 1830’s, Webster became one of its top leaders, along with his great rival, Henry Clay. His Whig friends thought he deserved to be president, and he ran as one of the party’s three candidates in 1836. His later failures to become president made him bitter at the end of his life. He died on Oct. 24, 1852. A statue of him represents New Hampshire in Statuary Hall in the U.S. Capitol.