Celtic art. The Celts expressed their artistic genius in such arts and crafts as metalwork, sculpture, and ceramics (pottery). Celtic artists excelled in decorating objects. They used beautiful combinations of curved lines and spirals that were based on natural forms such as plants, animals, and birds. The artists did not represent objects in a lifelike way but made them into abstract forms.

In the 400’s B.C., the Celts who lived in the Rhine valley began to develop an art with distinctive characteristics. Later, Celtic civilization spread to the areas that are now the Czech Republic, Austria, northern Italy, France, Spain, Britain, and Ireland. The art of the Celts on mainland Europe between 400 and 100 B.C. is called La Tene art. La Tene is an archaeological site on the edge of Lake Neuchatel, in Switzerland.

By 100 B.C., the civilization of the Celts on the mainland of Europe had greatly declined. But in England, Celtic art survived until about A.D. 150. The main forms of Celtic art survived much later in Ireland and Scotland, which were not conquered by the Romans. After the coming of Christianity to these countries, Celtic decoration became extremely intricate. This style survived in Ireland until the late 1100’s.

Ornamentation

Archaeologists believe that La Tene art was influenced by the art of the peoples of Greece and Italy. The Celts traded with these peoples, exchanging iron ore, slaves, and other goods for wine. The Greeks and Italians sold their wine in pottery vessels decorated with classical motifs of palmettes (ornaments like palm leaves), plant scrolls, animals, and human faces. Celtic craftworkers imitated these ornaments and developed a distinctive decorative art from them. They simplified the features of human faces, making them into highly stylized forms. They used these fanciful imitations to decorate torques (bronze or gold necklaces), bracelets, and chariots.

From the A.D. 600’s to the 1100’s, the Irish adopted and developed new patterns of ornamentation from various sources, adding them to the motifs of curves and spirals. The most interesting of these new patterns is animal interlacing, which was originally copied from decorations used by the Saxons. In animal interlacing, the elongated bodies of animals and birds are knotted and woven together to make a pattern. The overall design is generally regular, but the vividly depicted heads and paws of animals give it great animation. The curves are tightened into spirals which have, at their centers, interlaces or little birds’ heads.

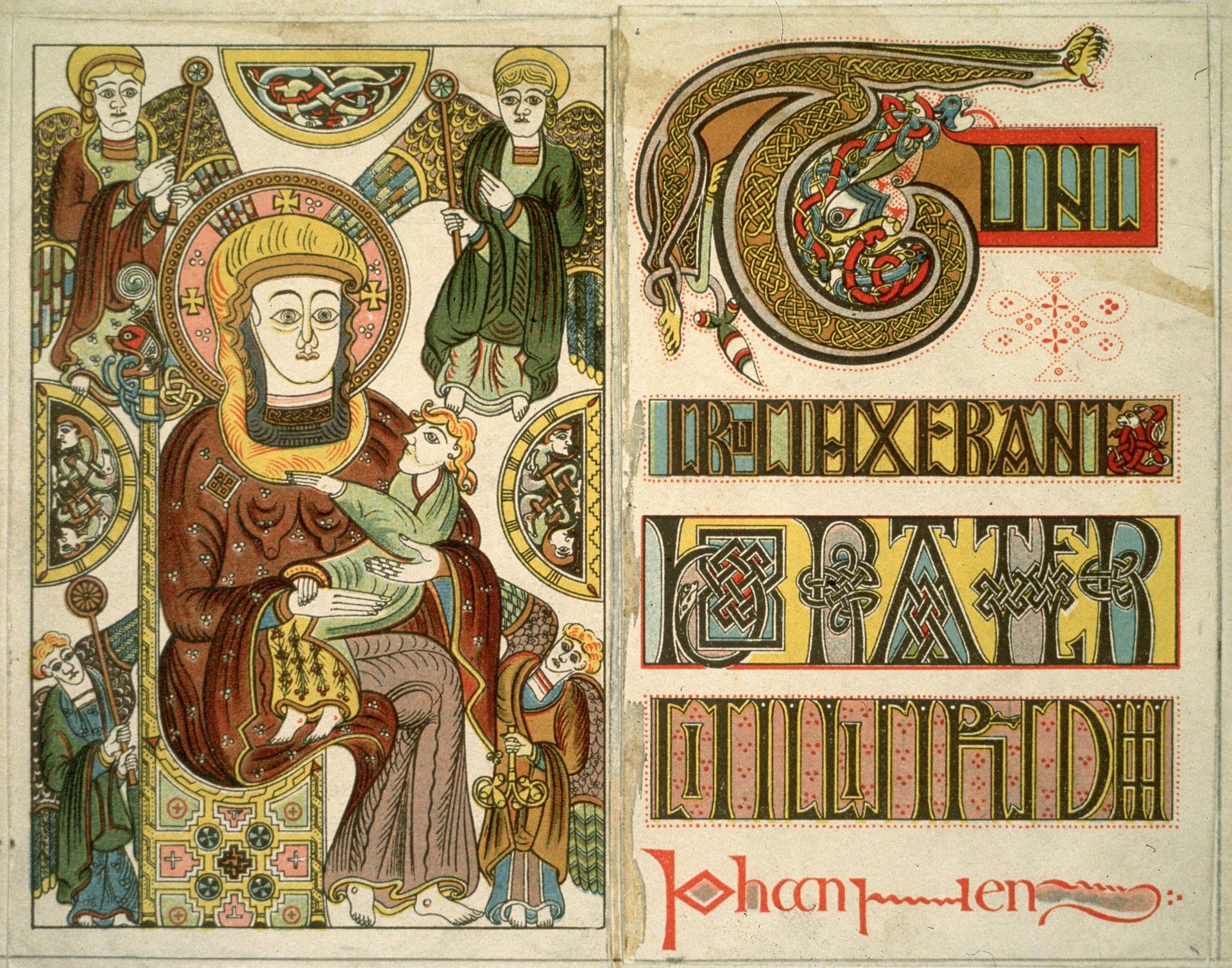

Irish monks used these patterns to illuminate (decorate) manuscripts, chiefly the Gospels. The monks wrote the manuscripts in beautiful, regular lettering. At the beginning of each gospel, they drew a decoration, with a “portrait” of the evangelist or his symbol on one page, and the beginning of the text on the other.

These “portraits” are not realistic. The evangelist’s dress and sometimes the features of his face are turned into ornaments. His clothes are represented by a series of colorful patterns. The beginning of the text consists of a few large letters spread over the whole page and overlaid with ornaments in bright colors. Some manuscripts have pages with illustrations of passages from the Gospels and a number of brightly colored initials in the text itself. Two of the most elaborate of these manuscripts are The Book of Kells and The Book of Durrow, both of which are in the Library of Trinity College, Dublin, Ireland.

Metalwork

Archaeologists have found many examples of La Tene art in tombs of Celtic chieftains in the Rhine valley. In these tombs, Celtic chieftains were buried with their chariots and other precious possessions. Less rich tombs of the same type in Champagne, in northeastern France, are of a slightly later date than those in the Rhine valley. They have yielded hundreds of bronze objects and a great quantity of pottery. The still later establishment at La Tene has yielded iron swords in beautifully engraved bronze scabbards.

The Celts worked these metal objects with great care. They used complex techniques, but they did not know how to cast large vases of bronze in one piece, as the smiths of Greece and Italy were able to do. Instead, the Celts made metal objects by beating a sheet of bronze into the required shape. They decorated metal objects with patterns raised in relief or engraved into the surface.

Celtic smiths decorated metals with insets of colored enamel, coral, or amber, or with studs of red, blue, or green glass. They were skilled in enameling, though the methods they used were simple. In southern Britain, shortly before the Roman conquest in A.D. 43, Celtic chieftains had the harness of their horses decorated with large plaques of enamel in several brilliant colors. Sometimes, craftworkers mounted little bosses of enamel on cores of clay to make them stand in relief. The enamel bosses had a grill of bronze over their surface. The Celts of southern Britain made round bronze mirrors with patterns engraved on the reverse side.

Irish craftworkers used similar patterns to decorate metal objects, mainly for use in churches. Irish smiths of the 700’s showed great skill in decorating chalices, reliquaries (receptacles for keeping relics of saints), and brooches. They used various metals, such as gilt bronze, silver, and gold. Fine metalwork made by these smiths includes the Ardagh Chalice and several brooches, the most famous of which is the Tara Brooch.

The 1100’s was one of the finest periods of Irish metalwork. The chief objects that have survived from that time are the shrine of the arm of Saint Lachtin and the Cross of Cong, made in the 1120’s for Turlough O’Connor, king of Connacht.

Sculpture

Early Celts made statues of human figures and animals in stone and bronze. Some of the statues of animals are fairly lifelike, but most of the human figures are extremely simplified in shape. Archaeologists have found several statues or fragments of statues in Germany, the Czech Republic, and Ireland. In southern France, they have found the remains of carvings that formed part of the door of a monument. Other Celtic carvings include stones decorated with patterns formed from curves or angular lines. Such stones have been found in the Rhine valley, Germany; in Brittany, France; and in Ireland.

In Ireland, high crosses stood in front of churches and in the courtyards between monastery buildings. Many crosses still survive. They vary in height, and most are made of several blocks of stone. One block is used for the wide base, one or two for the cross itself, and one for a capstone. The makers used the most suitable stone available in the neighborhood. Many crosses are made of soft, whitish sandstone found in the center of Ireland.

The earliest high crosses probably date from the mid-700’s. Similar crosses and stone slabs were cut in Scotland about the same time. The earliest crosses may have been imitations of metalwork. The crosses of later periods have carvings of figures and scenes, mainly from the Bible. As a rule, each scene is framed in a separate panel, but a general theme links all the scenes.

In the 1100’s, a new type of cross developed. Such crosses have carvings of almost life-sized figures in high relief. The churches of that period have carvings on their doorways. These doorways, in their general shape, are imitations of the doorways of Romanesque churches on the mainland of Europe. But their decoration includes the old Celtic patterns of interlacing and spirals.

Ceramics

La Tene pottery is beautifully made, but little, if any, was turned on a potter’s wheel. Celtic craftworkers gave their pots an angular shape and a black, polished surface, so that they look like metal vases. Some of the pottery has painted or engraved decoration that, in some cases, includes patterns of curved lines similar to those found on decorated metal objects.