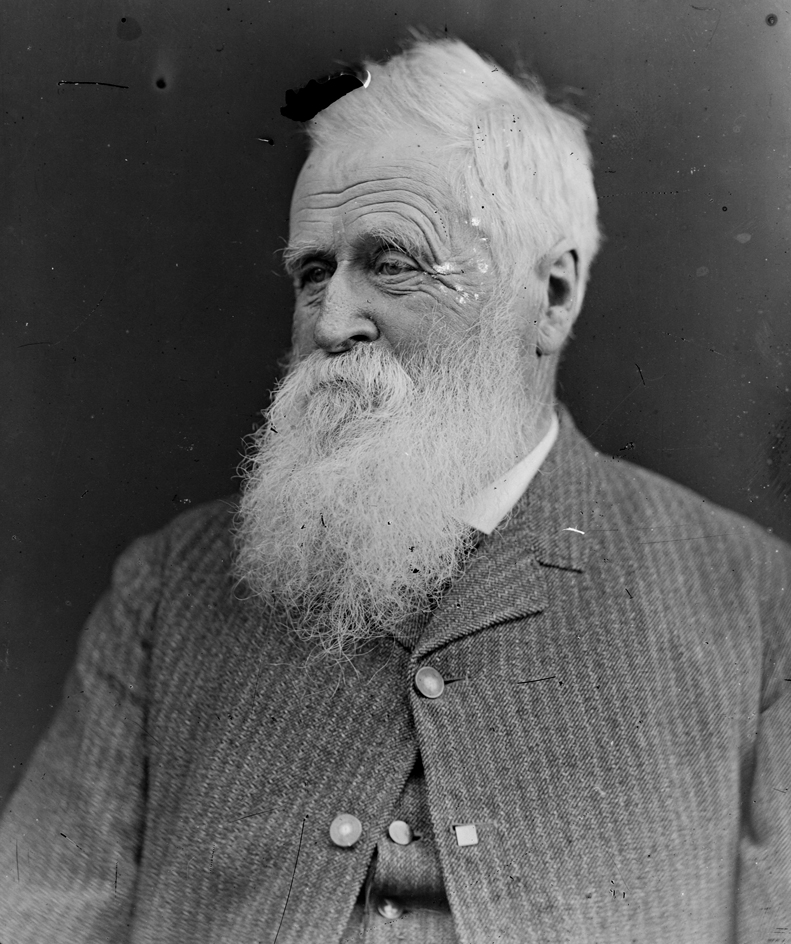

Fox, Sir William (1812-1893), served as premier (prime minister) of New Zealand four separate times: in 1856, from 1861 to 1862, from 1869 to 1872, and again in 1873. He served when New Zealand was a British colony. Political parties as we know them did not exist in New Zealand at that time, and Fox belonged to no party. Fox often criticized British actions in New Zealand. He wanted New Zealanders to have more control over colonial policy. He also was a supporter of free education.

Early life

Boyhood and education.

William Fox was born in the village of Westoe, England, near Durham, in 1812. The exact day of his birth is unknown, but he was baptized on September 2. His parents were George Townshend Fox, a justice of the peace and a minor official of County Durham, and Ann Stote Crofton Fox. Three of William’s brothers became ministers in the Church of England. William was educated at Oxford University, earning a B.A. degree in 1832 and an M.A. degree in 1839. In 1838, he began to study law. Fox became a member of the bar—that is, the body of lawyers licensed to practice law in England—in 1842.

Marriage and immigration to New Zealand.

Fox married Sarah Halcomb, the daughter of an English landowner, on May 3, 1842. Six weeks after their marriage, the young couple sailed to Wellington, in New Zealand’s North Island. The Foxes had no children, but in the 1870’s they helped to raise and educate a Māori << MOW ree or MAH ree >> boy.

Fox had become a follower of Edward Gibbon Wakefield, the founder of the New Zealand Company. The New Zealand Company was a group that promoted British colonization of New Zealand and had established several British settlements there. The couple arrived in New Zealand in November 1842. At first, Fox could not practice law in New Zealand. He refused to swear the required oath of good behavior, viewing it as an insult to his character. Instead, he worked as a journalist for The New Zealand Gazette and Wellington Spectator, New Zealand’s first newspaper, published in Wellington.

In 1843, the New Zealand Company appointed Fox as its agent in Nelson, in New Zealand’s South Island. Earlier that same year, he and three companions had traveled into the Wairarapa region in the North Island looking for land that would be suitable for farming. They were the first Europeans to visit the region. In 1845, Fox traveled through the country north of the Wairau River on the South Island. In 1846, he explored additional areas of the South Island around Rotoiti and Rotoroa Lakes and nearby river valleys, including Buller Gorge.

Fox was a talented painter. He made numerous sketches and water-color paintings of what he had seen during his travels. He submitted the works with his written reports to the New Zealand Company. Many of his paintings now hang in museums. The Hocken Library in Dunedin, New Zealand, and the Alexander Turnbull Library (part of the National Library of New Zealand) in Wellington have large collections of his works.

Political career

Entry into politics.

In 1848, the governor of New Zealand appointed Fox the attorney general (chief legal officer) for the province of New Munster. The province consisted of the South Island and the southern part of the North Island. Fox had become a believer in self-government for New Zealand, and he soon resigned because the governor did not think that change could be made immediately. Later in 1848, the New Zealand Company made Fox its principal agent in the colony.

In 1849, Fox bought land near Rangitikei, in the North Island. He built a country home that he called Westoe, in honor of his birthplace. In 1850, a group of settlers in the Wellington area chose Fox as their representative on a mission to England. The goal of the mission was to ask the British government to grant New Zealand a constitution. However, the Colonial Office, the British government agency responsible for the colonies, refused to meet with him.

While Fox and his wife were in England, he finished writing a book titled The Six Colonies of New Zealand (1851). The book describes colonial New Zealand. In it, Fox finds fault with British policy in New Zealand, especially regarding the actions leading up to the war with Māori that began in 1860. The book also has harsh words about Auckland, which was New Zealand’s capital at the time.

In 1852, after visiting their families, the Foxes left the United Kingdom and traveled to the United States, Canada, and Cuba. Fox painted many fine water colors of North American landscapes on the trip.

Also in 1852, the British government granted the colony of New Zealand a new constitution. The document incorporated some of the ideas Fox had supported, but he was not satisfied with it. His major criticism was that it did not provide for strong regional governments.

The Foxes returned to New Zealand in 1854. Soon after their return, Fox won a seat on the Wellington provincial council.

In 1855, Fox won election to the House of Representatives, the lower house of New Zealand’s colonial Parliament. He campaigned as a strong supporter of self-government for New Zealand’s provinces. Fox switched voting districts several times during his parliamentary career. He represented Wanganui from 1855 to 1860; Rangitikei from 1861 to 1865 and from 1868 to 1875; Wanganui again from 1876 to 1879; and Rangitikei in 1880 and 1881.

Prime minister.

In 1856, Fox sponsored a resolution in Parliament that overturned Prime Minister Henry Sewell, the first prime minister of New Zealand. Fox, who supported self-government for the provinces, disagreed with Prime Minister Sewell, who wanted a strong central government. Fox replaced Sewell and served as New Zealand’s second prime minister. However, Fox’s ideas on provincial self-government were too extreme for many people, and Aucklanders could not forget the insults in his book. His government lasted less than two weeks, from May 20 to June 2, 1856, before Edward Stafford replaced him.

Fox strongly opposed the British settlers’ war with Māori that had begun in 1860. This conflict was the start of what was later called the New Zealand Wars. Fox became a leader of the antiwar group in Parliament and led a campaign that ousted Prime Minister Stafford. On July 12, 1861, Fox became prime minister for the second time. He held the office for almost 13 months. He wanted the British government to transfer control of Māori affairs to New Zealand, but he lost an important vote on the issue in Parliament. Fox was forced to resign on Aug. 6, 1862, and Alfred Domett succeeded him. Fighting flared again in May 1863. Fox blamed some Māori groups for the new fighting, and this time he supported the war.

In October, Fox returned to government as colonial secretary under Prime Minister Frederick Whitaker. While Fox was colonial secretary, the Parliament of New Zealand passed the New Zealand Settlements Act of 1863. Under this act, the government seized about 3 million acres (1.2 million hectares) of Māori land as punishment for what it called the Māori rebellion.

After Whitaker’s government fell in 1864, Fox and his wife traveled to Australia. From there, they went to the United Kingdom in 1865. Fox wrote The War in New Zealand (1866) to defend the policies of the settlers in the fighting that had taken place since 1863 and to criticize the British military leaders in New Zealand. The Foxes returned to New Zealand in 1867. In 1868, Fox regained a seat in Parliament and quickly became leader of the opposition.

In 1869, Fox led a parliamentary motion of no confidence—a vote to challenge the government leadership—that led once again to the resignation of Prime Minister Stafford. Again Fox replaced him, becoming prime minister for the third time on June 28, 1869.

Fox had long supported the ideal of free, compulsory (required) education. During his third term in office, his government passed the New Zealand University Act 1870, which established the university.

The most powerful official in Fox’s third government was the colonial treasurer, Julius Vogel. To develop New Zealand’s economy, Vogel borrowed money from the British government to finance the construction of roads, railways, bridges, and telegraph lines. The economic policy of Fox and Vogel was popular. However, Fox failed to defend it well against critics in the House and lost a motion of no confidence in September 1872. He resigned on Sept. 10, 1872. He was succeeded by Edward Stafford, who held office only briefly.

George Waterhouse became prime minister, also briefly, with Vogel again serving as colonial treasurer and the most powerful official in government. Vogel was overseas when Prime Minister Waterhouse resigned, so Fox became prime minister for the fourth and last time on March 3, 1873. He served as caretaker (temporary) prime minister until Vogel returned. Vogel took office on April 8.

Later years

Fox had supported the temperance movement, a drive to end of the use of alcoholic beverages, since the 1840’s. In 1875, he traveled to the United Kingdom. He spent several years there and lectured for the United Kingdom Alliance, a temperance organization. In 1879, Queen Victoria granted him a knighthood, and he became known as Sir William Fox.

In 1880, the British government appointed him to the Commission of Inquiry, often called the West Coast Commission. The panel’s job was to investigate promises that previous governments had made to Māori and to resolve land disputes. The West Coast Commission identified more than 200,000 acres (81,000 hectares) to be returned to Māori. However, much of the land was rugged or difficult to reach.

Fox lost his seat in Parliament in 1881. After retiring from politics, Fox wrote newspaper columns and political pamphlets. He devoted much of his time to delivering temperance lectures. He also urged other reforms, including voting rights for women, which New Zealand enacted in 1893, and free, compulsory education. In 1886, he helped found and became the first president of a temperance organization called the New Zealand Alliance.

In 1887, Sir William and Lady Fox moved from their country estate, Westoe, to Auckland. In 1890, he climbed Mount Egmont (now also known as Mount Taranaki), a peak that rises 8,260 feet (2,518 meters) in the North Island. He made the climb to demonstrate the health benefits of avoiding alcohol.

Lady Fox died in Auckland on June 23, 1892. Sir William died there exactly a year later, on June 23, 1893.

See also Vogel, Sir Julius ; Wakefield, Edward Gibbon .