Odisha (pop. 41,974,218) is a state on the northeastern coast of India. It was formerly known as Orissa. Odisha receives few visitors despite the fame of the Sun Temple at Konarak and the Jagannath Temple in Puri. The capital and largest city of the state of Odisha, Bhubaneshwar, has some of the finest temples in India, dating from the 600’s. Odisha covers an area of 60,119 square miles (155,707 square kilometers).

People and government

People.

Odisha has a lower population density than the rest of India. It is one of the major Hindu states. About 95 percent of the population are Hindus. The majority speak Odia, an Indo-European language, but there are also many minor languages and dialects.

There are about 60 adivasi (ancient inhabitants) or ethnic groups living in forest and remote hill regions of the state. Each group has its own language, social customs, and artistic, music, and dance traditions. Several groups still use bows and arrows to hunt (hunting is a main source of food) and to defend themselves against enemies.

The Kondhs, who live mostly in the western districts, used to carry out human sacrifice. Today, they have replaced this with animal sacrifice, which they perform at the time of sowing seeds. The aim of the sacrifice is to ensure a good crop. The Bondas live in the Khairaput block of the Malkangiri district. They live in the remoter high hills and grow rice in forest clearings. The Santhals come from the northern districts of Mayurbhanji and Balasore. Their language is one of the oldest in India. In the northwestern industrial belt, people have abandoned their aboriginal lifestyle to work in the steel mills in that region.

Despite rapid industrial growth, Odisha is one of the least urbanized states in India. Most of the people live in rural areas. Bhubaneshwar, the capital, is the state’s largest city.

Government.

Odisha took its present form in 1949. It has 21 elected members in the Lok Sabha (lower house) and 10 elected representatives in the Rajya Sabha (upper house) of the Indian national Parliament. Odisha has only one legislative chamber, its state Legislative Assembly. It has 147 seats.

Economy

Agriculture.

The traditional farming method in Odisha was shifting cultivation. The farmers made clearings in the forest, cultivated them for a few years, and then left them to recover their natural fertility. Even as recently as the 1960’s, shifting cultivators removed more than 71/2 million acres (3 million hectares) of forest every year. Since then, settled farming in the hills has developed extensively. Rice and millet dominate farming in the interior of Odisha. Rice is the major crop grown on the fertile plains of the Mahanadi Delta. There are also small areas of gram (lentils), jute, oilseeds, and ragi (a grain crop).

Forests cover much of the state. The main forest products are sal (a timber tree), teak, medicinal plants, and lac (a resin used for varnishes).

Manufacturing.

Since the early 1980’s, there have been major developments in industry in Odisha. Aluminium smelting plants use local bauxite (aluminium-bearing ore) and hydroelectricity. There is a steelworks at Rourkela. Some of the development has taken place with the help of overseas aid. Despite recent growth, Odisha still provides only a small proportion of India’s factory employment. The Industrial Development Corporation in Odisha organizes cable works, cement works, spinning and textile mills, and the steelworks.

Local crafts.

Various traditional crafts operate on a commercial basis. Craftworkers carve delicate images, bowls, and plates out of soft soapstone, hard konchila stone, or multicolored serpentine stone from Khiching. In Parlakhemundi and Cuttack, people carve buffalo horn into small, flat figures of animals and birds.

Silver filigree is the most famous work of the Cuttack jewelers. They turn fine silver wire into intricate objects such as small boxes and trays with floral patterns. The ethnic metal casting in the dhokra style by the lost wax process flourishes in the Mayurbhanj district. Metal workers place a clay shell around a wax core and pour a molten metal into the shape. The wax melts away and the metal fills the space.

Other traditional crafts include wood carving, inlay of ivory on wood, and the making of papier-mâché masks. Picture makers, particularly from the village of Raghurajpur near Puri, paint pattachitras on specially prepared cloth. They coat the cloth with earth to stiffen it and finish it with lacquer after painting.

Textile weaving, which has been a traditional handicraft throughout Odisha for generations, continues to employ thousands of people. The favorite designs include rows of flowers, birds, animals (particularly elephants), and geometric shapes, using either tussore (silk) or cotton yarn. Colorful applique work, decorating embroidered cloth for use in temples, is done near Puri. Roadside shops sell items for the house and garden, such as sun umbrellas and cushion covers.

Another skill that is still practiced is palm leaf etching. A sharp iron “pen” is held motionless against the hard leaf of the palmyra palm. Moving the leaf produces lines upon it. This was the way in which early books were produced, and helped to give the Oriya script its rounded form. Beautifully illustrated manuscripts are still produced in this way.

Mining.

The ancient rocks of inland Odisha contain some of India’s richest mineral resources. There are thick seams of coal in the mines at Talcher, 62 miles (100 kilometers) to the northwest of Bhubaneshwar. Around Bhubaneshwar, and at several other sites in the interior, there are important bauxite deposits. Bauxite mining began there in the 1980’s.

Odisha also has reserves of dolomite, iron ore, manganese, and limestone. The far north of the state, especially between Keonjihar and Rourkela, has enormous reserves of high-grade iron. There are also important reserves of chromite, graphite, ilmenite, and mica.

Mining began only after independence in 1947. A port at Paradip handles mineral exports.

Transportation.

National highways run down the old coast road and across the north of the state, as part of the link between Kolkata and Mumbai. The rail network is less extensive. Parts of the interior remain remote. Some of the hills in the southwest are still forested, and few roads have been developed.

Land and climate

Location and description.

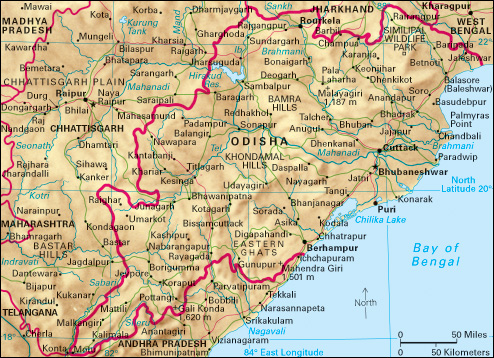

Odisha is bounded by West Bengal and Jharkhand to the north, Chhattisgarh to the west, and Andhra Pradesh and Telangana to the south. To the southeast lies the Bay of Bengal. The whole of the state is south of the Tropic of Cancer, and midway between the semitropical, wet deltas of Bengal and the much drier tropical interior of the Peninsula.

In the far north is the ancient, volcanic Simlipal Massif. It rises to a height of more than 3,300 feet (1,000 meters) from the surrounding plateau and is a continuation of the Chota Nagpur region. In the south, a series of hills known as the Eastern Ghats rises to heights of 5,000 feet (1,500 meters). Also in the south of the state are the beautiful lakes of Khairaput. Between these two regions are gently rolling plains.

Down the east coast runs a flat alluvial plain (land formed from soil deposited by rivers), with the Mahanadi Delta at the center. Occasional low mounds of granite, such as the hill at Dhauli, break the otherwise straight horizon. The delta stretches nearly 105 miles (170 kilometers). In many places, the delta is more than 50 miles (80 kilometers) wide. The Hirakud Dam Project is a multipurpose river valley project to provide irrigation, power generation, flood control, and navigation. The Hirakud Dam, one of the largest in Asia, controls the Mahanadi River, which used to do great damage during the flood season. There is a huge reservoir behind the dam.

The natural vegetation of the highlands of Odisha is dense with deciduous trees (trees that shed their leaves annually). The forest area decreased greatly in the 1980’s due to extensive felling of trees and the clearing of land for cultivation.

Because great areas of forest have been settled by farmers, the habitat of bison, elephants, tigers, and other large animals that were once widespread has been reduced. They are now largely confined to game reserves. In the Simlipal region there are still chital (spotted deer), flying squirrels, gaur (wild ox), leopard, sambar (large deer), and wolves. There is also a variety of wild fowl including mynas, parakeets, and peacocks.

Rivers and lakes.

Most rivers flow southeast through the state from the peninsular plateau to the Bay of Bengal. The Mahanadi and the Brahmani are two of the larger ones. They rise in the forested hills and enter the sea across the Mahanadi Delta. Other important rivers are the Subarnarekha, the Rushikulya, and the Tel. There are several artificially created and natural lakes in the hills of the interior. Lake Chilika is the largest coastal lagoon in India. It varies in size from 350 to 460 square miles (900 to 1,200 square kilometers). Water in the lagoon alternates between being salty and being fresh. Although the lagoon is large, it is only a few meters deep. It has a very rich marine and bird life.

Climate.

Temperatures vary according to altitude. On the plains around Bhubaneshwar, just south of the Tropic of Cancer, the average maximum temperature in December, the coldest month, is 82 °F (28 °C), and minimum temperatures do not fall below 61 °F (16 °C). In April and May, the hottest months, maximum temperatures soar to 100 °F (38 °C). The average minimum temperature from April to September is between 77 °F (25 °C) and 81 °F (27 °C).

Annual rainfall along the coast decreases southward from nearly 63 inches (160 centimeters) at Balasore to just over 43 inches (110 centimeters) at Chatrapur. But the inland hills in the far southwest receive much more rain than the nearby coastal strip. The major part of Odisha has one of the shortest dry seasons in India with only January and February being rainless.

History

What is now Odisha was part of the ancient kingdom of Kalinga. It first grew prosperous through trade. Kalinganagar port developed as early as 300 B.C. Java, Sumatra, Borneo, and Bali all established relations with the kings of Kalinga.

The Mauryan king Ashoka conquered and annexed the Kalingan kingdom in about 260 B.C. (see Ashoka). Odisha, then known as Orissa, regained its independence in about 100 B.C. under the local king Kharavela. He was a Jain, and perhaps the greatest of the Kalinga kings. His achievements in extending his empire and descriptions of his capital are recorded in an inscription in the Udayagiri Caves near Bhubaneshwar. His exploits included military expeditions in which he defeated the king of the Deccan.

After Kharavela, two separate areas in the north and center of the Odisha region developed. Their names were Utkal (a region where the arts excelled) and Toshali. During this time, sea trade flourished, and Buddhism once again became a popular religion.

Two dynasties had a major effect upon the history of Odisha. The rule of the Kesaris (A.D. 600-1076) and the Gangas (1076-1435) saw the development of a style of temple architecture often referred to as Indo-Aryan. The temples in and around Bhubaneshwar were built by the kings of the Kesari dynasty. The founder of the Ganga dynasty, Choda Ganga (ruled 1076-1148), was a devout Hindu and a patron of art and literature. He built the great temple of Jagannath at Puri. The most famous ruler of the Ganga dynasty was Narasimha I (ruled 1238-1264). He was responsible for the construction of the temple of the Sun God at Konarak.

The Gangas became rich through trade and commerce and used their wealth to finance their temple-building. By the early 1400’s, their power was already starting to decline. The Surya dynasty took control in 1435 and ruled Orissa until 1542.

During medieval times, Orissa had been powerful enough and remote enough to resist Muslim invasions from the north in the 1200’s. But for a time Afghans held Orissa in the 1500’s, and powerful Mughals arrived as conquerors in 1592. The Mughal emperor Akbar annexed it in that year. With the decline of the Mughals in the 1700’s, the Marathas occupied Orissa for a time until the British took it over.

In 1765, after the victory of the British military leader Robert Clive at Plassey, the East India Company acquired parts of Orissa. Cuttack and Puri came under British control in 1803. Many interior areas remained under princely rule, subject to the authority of the United Kingdom, until India gained its independence in 1947.

During British rule, several revolts took place in Orissa. The significant ones included the Paik Rebellion of 1817, the Ghumsar risings of 1836-1856, and the Sambalpur revolt of 1857-1864. These uprisings were put down by the British administration but promoted growth of anticolonial consciousness in Orissa.

After the British conquest of India, the Oriya-speaking areas were placed under different administrative units known as the Bengal Presidency, the Madras Presidency, and the Central Provinces. The Utkal Union Movement, which aimed at unifying all Oriya-speaking areas into one administrative unit, began in the late 1800’s. The movement was ultimately successful, and the province of Orissa was established in 1936.

Along with the Utkal Union Movement, the wider struggle for the freedom of all India also became popular in Orissa. The Swadashi, the Non-cooperation, the Civil Disobedience, and the Quit India movements all won wide and vigorous support in this region. In the princely states, the Orissa States Peoples Conference, which was founded in 1931, campaigned against the oppression of feudal rulers and on behalf of democratic rights.

At the time of independence in 1947, all the princely states chose to be part of the Indian union. In Orissa, Congress became the dominant party and was in power for a long period. In 1991, Janata Dal became the ruling party in Orissa. In 2011, the state was renamed Odisha.