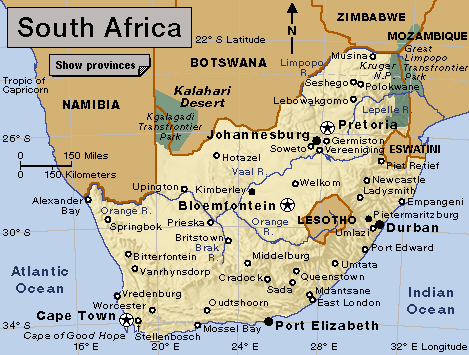

Soweto << suh WAY toh >> is South Africa’s largest urban Black African community. It is part of the city of Johannesburg, which is the largest city in South Africa and the capital of Gauteng province. The Soweto area covers about 60 square miles (155 square kilometers) and has a population of about 1,700,000. Johannesburg as a whole has a population of 4,803,262.

Soweto was formed from several townships that were established in stages starting in the early 1900’s. The name Soweto comes from the first two letters of each of the words South Western Townships. Soweto became part of Johannesburg in 1995.

The community

Soweto lies on the Highveld, which is part of the interior plateau of South Africa. The Klip River flows along the south and west sides of Soweto. Famous landmarks in Soweto include Regina Mundi, Soweto’s largest Roman Catholic church; and Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital, the largest hospital in Africa.

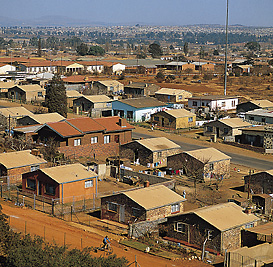

Soweto consists mainly of residences—apartment buildings, hostels (inexpensive lodgings), houses, and shacks. The average number of people living in a house is five. However, more than three times that many live in some houses. Most residents of Soweto’s hostels are migrant laborers. The hostels were originally built as single-sex residences, but in the mid-1990’s, they began to be converted to allow families to live in them. Thousands of shacks have been erected in squatter camps. There are also thousands of backyard shacks behind houses. People living in these shacks pay rent to the owner of the house.

Soweto is made up of about 30 areas that are often called townships or suburbs. Many of the townships were established under South Africa’s former policy of racial segregation known as apartheid (see Apartheid). Apartheid lasted from the late 1940’s to the early 1990’s. People sometimes refer to all of Soweto as a single township or a single suburb of Johannesburg.

People

Soweto has the most diverse Black African population of any part of South Africa. People from a number of ethnic groups live in Soweto. Since the late 1800’s, the Johannesburg area has attracted migrants from all over southern Africa, mainly from rural regions. Many of these migrants have settled in Soweto.

Zulu (which Africans call isiZulu), Sesotho, Tswana (Setswana), Xhosa (isiXhosa), and English are the main languages of Soweto. Many other languages also are spoken there. Soweto has a university campus and more than 300 schools. Much socializing in Soweto takes place in shebeens (taverns). Soccer is the most popular sport. Soweto has a major soccer stadium commonly known as “Soccer City.”

Religion is an important part of life in Soweto. Most Sowetans are practicing Christians. African independent churches, which combine Christian and traditional African beliefs, have the biggest following. The largest African independent church is the Zion Christian Church. Other leading Christian churches include the Anglican, Lutheran, Methodist, and Roman Catholic churches. Since the late 1900’s, African Pentecostal churches have experienced rapid growth.

Economy

There is little formal business, commerce, or industry in Soweto, and there are almost no large commercial or industrial properties. However, there are many small groups of shops. Much buying and selling takes place informally at pavement stalls (called spaza shops) and markets. Many Sowetans work in central Johannesburg or in other parts of the city. Most commuters from Soweto travel by train or in small buses called minitaxis. Although some Sowetans belong to the upper and middle classes, a large number of Sowetans face poverty and unemployment.

History

Origins.

Gold was discovered in 1886 in the Witwatersrand region in what is now Gauteng province (see Witwatersrand). Later that year, the town of Johannesburg was established in the region. Thousands of people, including many Black Africans, flocked there. The population grew quickly as the gold-mining industry developed. By 1913, Johannesburg had a population of about 250,000, half of whom were Black Africans.

Starting in the early 1900’s, the white Europeans who controlled the local, colonial, and national governments made repeated efforts to impose racial segregation in the Johannesburg area. In 1904, an outbreak of bubonic plague occurred in a racially mixed community on the west side of Johannesburg. In 1905, the community was burned down, and its Black African residents were moved to Klipspruit, about 12 miles (19 kilometers) south. Klipspruit was the original site of what would become Soweto.

In the 1920’s and 1930’s, the South African government and the Johannesburg City Council passed legislation to further extend racial segregation. The City Council planned and established the township of Orlando near Klipspruit around 1930. Orlando was the second part of what would become Soweto. In 1934, a part of Klipspruit was renamed Pimville.

Rapid population growth.

During World War II (1939-1945), South Africa’s manufacturing sector expanded rapidly, with much of the growth concentrated around Johannesburg. Vast numbers of Black African jobseekers flooded into the area, causing massive overcrowding. The Black African population of Johannesburg jumped from about 230,000 in 1936 to about 455,000 in 1948. During this period, the Johannesburg council was forced to allow tenants in Orlando and Pimville to rent out rooms to subtenants.

In March 1944, in response to the overcrowding problem, an Orlando leader named James “Sofasonke” Mpanza led a large group of subtenants to an open area outside of Orlando. There, without the permission of the Johannesburg council, he established a squatter camp that came to be known as Masakeng. Mpanza is often called the father of Soweto. The squatter camp grew rapidly and soon had thousands of shacks. Similar land invasions took place in the next several years. These land invasions forced the City Council to provide informal residential accommodations and services for Black Africans at Jabavu and Moroka, to the west.

Home construction.

Formal housing for Black Africans took longer to build. By 1954, 10,000 small brick houses—often called “matchbox” homes—had been built in the area. But these homes could accommodate only a fraction of the Black Africans who were living on informal residential sites. In 1956, Sir Ernest Oppenheimer of the Anglo-American Corporation, a large mining company, gave a loan to the Johannesburg council for home construction. From 1954 to 1959, 24,000 more houses were built, and a number of new townships were laid out.

The South African government also built about 24,000 houses in the communities of Meadowlands and Diepkloof in the mid-1950’s. These houses were built to accommodate families evicted from Sophiatown, Newclare, and other freehold townships in Johannesburg. Freehold townships were urban areas where Black Africans were allowed to own land.

Most of the houses in the new townships were built according to a single design, and streets were laid out according to a standard pattern. Leisure and shopping facilities were minimal, and only a few secondary schools were built. Starting in 1955, single-sex hostels were constructed for male migrant workers. Black Africans were assigned to certain townships or hostels based on their ethnic group.

A new name.

By the end of the 1950’s, the area had a population of about 500,000, but it had no name. In 1959, the Johannesburg council launched a competition to find one. Four years later, in 1963, the council chose the name Soweto, an abbreviation of South Western Townships.

In the late 1960’s, new development in Soweto, including the construction of houses, stopped. The South African government instead directed all its resources and attention toward the homelands—the mainly rural areas in South Africa set aside for Black Africans. The government’s intent was to encourage or force Black Africans to relocate to the homelands.

In the 1960’s and 1970’s, Soweto began to gain recognition for its cultural contributions. Black Africans throughout urban South Africa admired Soweto’s fashion sense, music, poetry, and soccer teams. During this period, Soweto also became a center of the Black Consciousness movement. This movement promoted self-respect and self-reliance among Black Africans and urged an end to white domination.

The 1976 uprising.

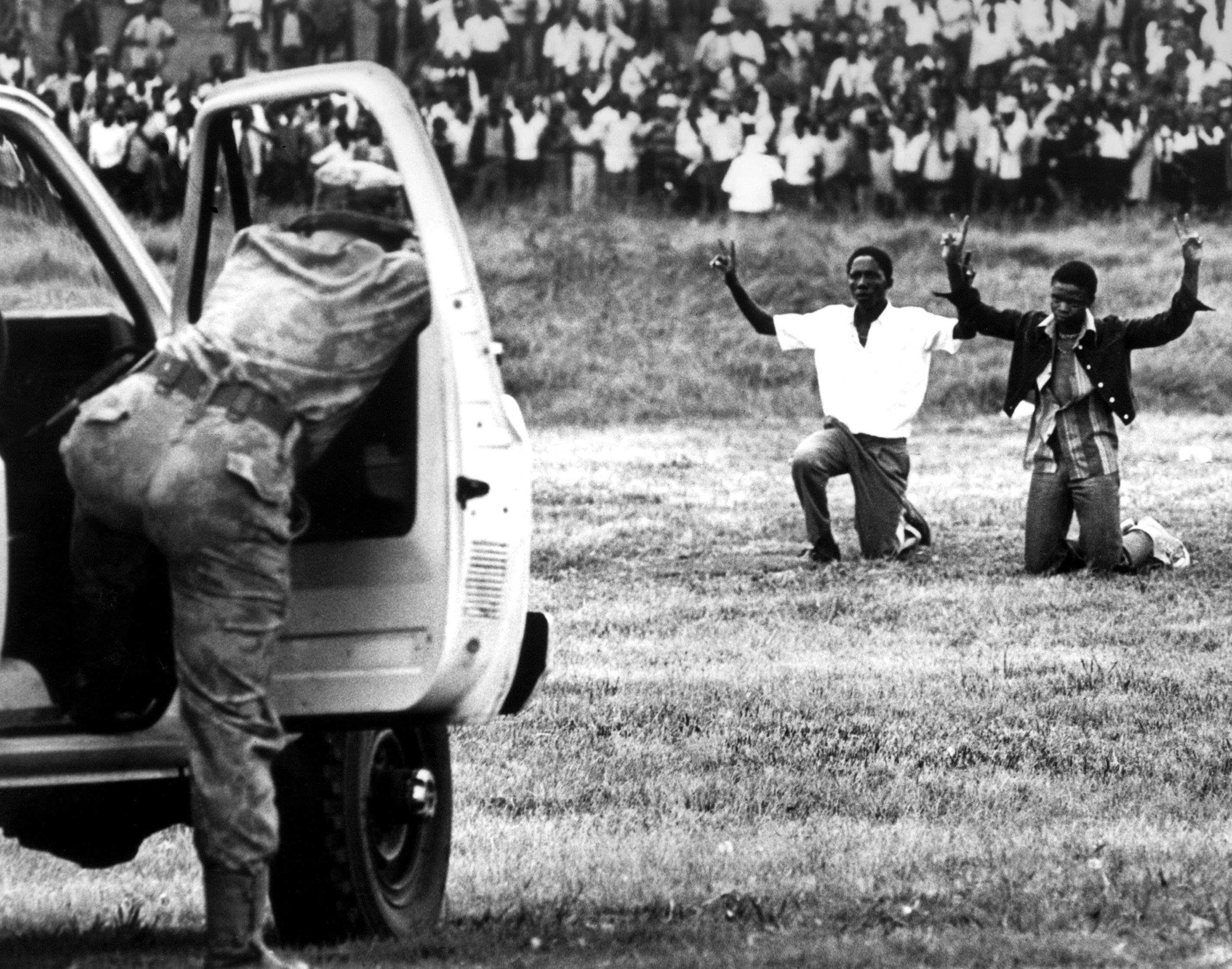

In 1973, the South African government transferred control of Soweto from the Johannesburg City Council to the West Rand Administration Board. The board toughened restrictions on Sowetans. Its harsh approach, combined with an education crisis in Soweto’s junior high and secondary schools, triggered a student uprising in 1976. The education crisis arose partly because of a government requirement that half of all school subjects be taught in Afrikaans—the language of the whites who controlled the government.

On June 16, 1976, thousands of schoolchildren marched in Soweto to protest the use of Afrikaans in the schools. Police opened fire on the children, killing two and wounding several others. This action prompted disturbances in many parts of South Africa during the next few months. Several clashes erupted between Black Africans and the police, and at least 575 people, almost all of them young Black Africans, were killed. The Soweto uprising and its aftermath motivated Black Africans to become more organized in their struggle for freedom.

Soon after the uprising, the South African government enacted some reforms. It recognized Black African trade unions, allowed township residents to take possession of their property under 99-year leases, and promoted a Black middle class. In Soweto, the construction of new schools and houses resumed, bringing an end to a long period of no development.

Rent protests.

The government put Black Local Authorities in charge of Soweto’s townships in 1982. But these bodies were not respected by the people, and they had few options to generate revenue, because the townships had little industry or commerce. Most revenue came from rents and charges for services, and thus there were increases in these during the 1980’s. The increases, combined with general dissatisfaction, sparked a wave of rent boycotts and other protests in Soweto and elsewhere.

In the mid-1980’s, the government began to slowly relax or abolish key restrictions of apartheid—the racial segregation policy that had been in place since the late 1940’s. As restrictions on the movement of Black Africans were eased, many thousands of unemployed people from rural areas flooded into the towns. Squatter camps grew dramatically, and large numbers of shacks were erected. At the same time, Sowetans began streaming out of Soweto to move into the inner city of Johannesburg.

The rent boycotts of the 1980’s paralyzed the administration and development of Soweto. In 1990, after about a year of negotiations, local and regional governments and civic organizations signed an accord that canceled past-due rents and ended the boycott.

In 1990 and 1991, South Africa repealed the last of its apartheid laws, and in 1993, Black Africans received full voting rights. The country held its first elections open to all races in 1994. However, from 1990 to 1994, there was frequent violence between rival Black African groups in South Africa, and about 1,000 Sowetans lost their lives as a result. Meanwhile, South Africa’s economy stalled, and many people were unable to find work.

Restructuring.

In 1995, the Greater Johannesburg metropolitan area was restructured. The administration of the region was divided between an elected council for the entire metropolitan area and local elected councils for four metropolitan “substructures.” Soweto was divided among the substructures. In 2000, the government of Johannesburg was changed again to create a metropolitan municipality, or “unicity,” governed by a single elected city council. This municipality includes Soweto.

The early 2000’s.

The economy of Soweto and the rest of South Africa began to improve in the early 2000’s. However, unemployment remained a significant problem in Soweto.

See also Johannesburg.