Waitangi, << WY tuhng ee or WY tahng ee >> Treaty of, was an agreement in 1840 between New Zealand’s native Māori << MOW ree or MAH ree >> people and representatives of the British government. Under the treaty, Māori effectively gave sovereignty (control and authority) over their lands to the United Kingdom. In return, the British government agreed to recognize full Māori ownership of their lands, villages, forests, and fisheries for as long as they wished to keep them. The British government also promised to protect Māori and to give them the rights of British subjects. The treaty was a foundation for establishing New Zealand as a British colony. However, translation problems between the English and Māori versions of the treaty have caused confusion about the exact terms of the agreement. For example, the English-language version gives the British full sovereignty over Māori lands, but the Māori version can be interpreted to mean a more limited authority to govern.

Early Māori-European contact.

James Cook, a British sea captain, first visited New Zealand in 1769. At that time, he estimated the Māori population at about 100,000. Following Cook’s explorations, growing numbers of European traders, seal and whale hunters, and missionaries came to New Zealand, mostly in the north. Many of these visitors survived with the support of powerful Māori groups who were eager to trade with the newcomers.

By the 1830’s, the work of English Protestant missionaries in New Zealand had expanded, and larger numbers of Māori were coming into contact with foreign influences. Around the same time, the growth of trade and settlement from the colony of New South Wales in Australia had made New Zealand, in many ways, an economic extension of that colony. Some missionaries, traders, and others began calling for the British government to exercise increased control over New Zealand, where maintaining law and order had become a concern for both Europeans and Māori. However, many people in the British government were reluctant to take on the responsibility and expense of a new colony. Some officials also feared that further British intrusion might be harmful to Māori welfare.

In 1833, James Busby arrived to serve as Official British Resident (government representative) in New Zealand. The British government had appointed him to oversee British interests and protect Māori welfare. In 1835, Busby and a group of Māori leaders—called the Confederation of Chiefs of the United Tribes of New Zealand—signed a Declaration of Independence. The document requested that the British monarch act as New Zealand’s protector, but also recognized Māori sovereignty.

In 1839, however, the British government decided to annex (take control of) New Zealand and make it a British colony. One reason for the decision was that some settlers and land speculators had been purchasing Māori land in transactions of questionable legality. There were additional concerns, because the New Zealand Company—a British settlement association that lacked the British government’s approval—planned to colonize large amounts of land.

The British government selected the naval officer William Hobson to serve as consul (foreign representative) to New Zealand. Before Hobson sailed from Britain in August 1839, the government instructed him to negotiate a treaty with Māori leaders to acquire sovereignty over the land. The British government planned for Hobson to serve as lieutenant governor of New Zealand once the treaty was in place.

In anticipation of the success of his mission, Hobson assumed his role as lieutenant governor immediately following his arrival in New Zealand on Jan. 29, 1840. In the following days, the terms of the treaty were drawn up in English and translated into Māori.

Signing the treaty.

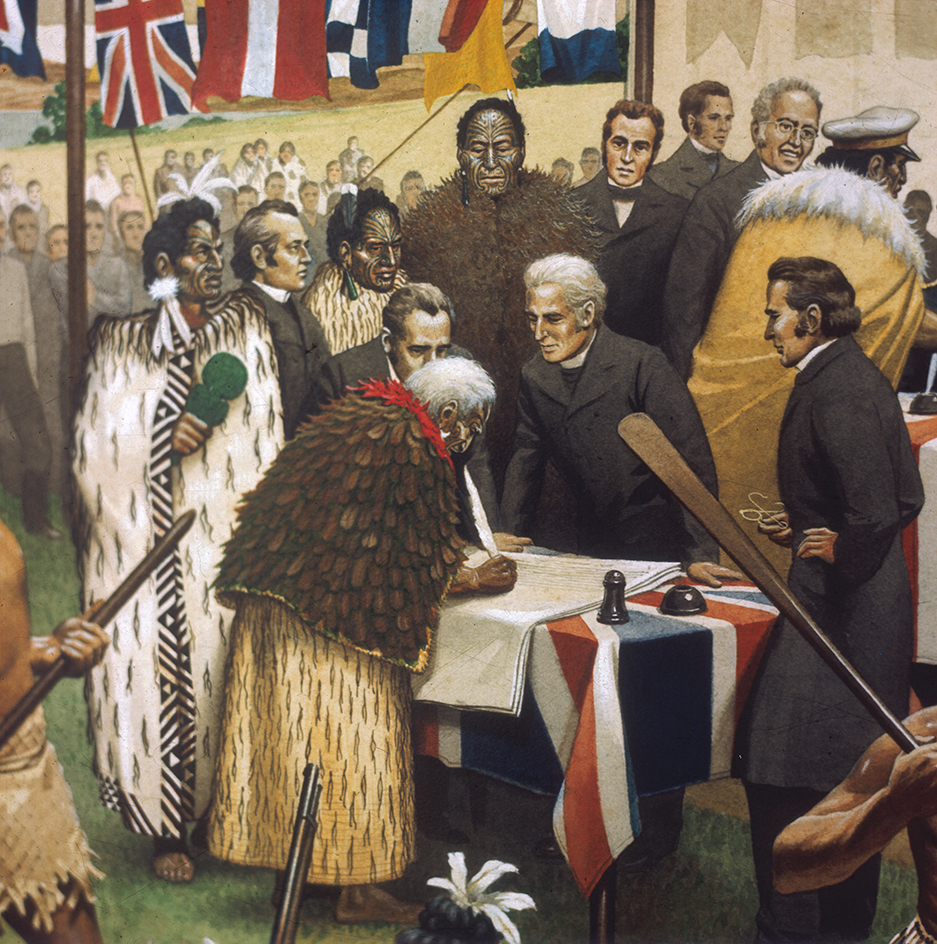

On February 5, Hobson called a meeting of Māori chiefs at Waitangi, the site of Busby’s home on the Bay of Islands. The treaty was read to the assembly in the Māori language, and heated debate among the chiefs followed. Some chiefs spoke out against the treaty and expressed doubts that Hobson and the British government would prevent further land loss. Others complained about past unjust deals with Europeans and voiced concerns about the loss of independence. But many chiefs—especially those who had close contact with missionaries—argued in favor of the agreement.

On February 6, more than 40 Māori chiefs agreed to the treaty. The chiefs signed the document or drew on it their moko, part of their facial tattoo designs. Hobson signed on behalf of the British government. Within a week, the names of several dozen more chiefs were added to the treaty.

The chiefs who initially signed the treaty were from the north of the country, so only part of New Zealand had formally been ceded (given up). British officers and missionaries sought to confirm authority over the rest of New Zealand by persuading chiefs elsewhere to add their signatures or moko. They were successful in obtaining agreements in most areas. By September 1840, more than 500 chiefs and several women of high rank had agreed to the treaty. However, some important leaders—including Mananui Te Heuheu Tūkino II, who held influence in the central North Island, and Te Wherowhero, the major Waikato chief—refused.

Hobson proclaimed New Zealand a British colony on May 21, 1840, even though many chiefs had not yet signed the treaty. He based his proclamation on the idea that the treaty established British control over the North Island and that James Cook had discovered and established a claim to the South Island and Stewart Island. Meanwhile, another government officer, Thomas Bunbury, was traveling through South Island collecting signatures. In June, he made additional proclamations of British sovereignty over the South and Stewart islands. The publication of Hobson’s proclamations in London in October 1840 confirmed that New Zealand was a British colony.

Confusion and criticism.

Since 1840, the Treaty of Waitangi has been the subject of considerable criticism and debate. Questions over the translation of certain words have led to disputes over which rights the Māori kept and which they signed away. Only 39 chiefs signed the English version of the treaty, which the British government considered the “official” version. The other chiefs signed the Māori translation.

The English version stated that the chiefs gave up their sovereignty but that they kept possession of their lands and gained protection and all the rights of British subjects. The Māori version, however, divided the powers of authority into two: kāwanatanga (governorship), which went to the British, and rangatiratanga (chieftainship), translating loosely to the possession of Māori lands, estates, forests, fisheries, and other properties, which were to be retained by Māori.

New Zealanders of non-Māori ancestry—known as Pākehā (pronounced PAH kee hah)—have traditionally regarded the English version of the treaty as the true version. Many have celebrated the treaty’s efforts to grant Māori the rights of British subjects and to include them in European settler society. However, a number of Māori protests have charged that the treaty has never been fully understood and that the British government has not fulfilled its obligations. Many Māori argue that certain government policies have sought to undermine Māori customs, values, and systems of land possession.

The Waitangi Tribunal.

Throughout much of the 1900’s, the Māori people sought to remind the British government of its obligations under the treaty. In 1975, in response to Māori demand and international calls for Indigenous (native) rights, the New Zealand Parliament established a judicial panel called the Waitangi Tribunal. The tribunal was given the power to interpret the principles of the Treaty of Waitangi, to consider claims involving alleged breaches (violations) of the treaty, and to recommend appropriate compensation for breaches.

The Waitangi Tribunal originally could hear only contemporary claims—that is, claims that originated from laws passed or actions taken after the act that created the tribunal went into effect in 1975. As a result, the majority of Māori claims were excluded. In 1985, however, new legislation allowed the tribunal to consider claims from 1840 onward. Since the mid-1980’s, numerous claims have been registered. In many cases, the tribunal has recommended the return of land and other resources to Māori groups.

Waitangi Day.

The Waitangi Day Act 1960 set February 6, the date of the treaty’s original signing, as Waitangi Day. Many New Zealanders view the treaty as the nation’s founding agreement. Although the treaty has no formal legal status, it has been cited in acts of Parliament and recognized in New Zealand courts.