Mexican Revolution of 1910 was a civil war that took place in Mexico from 1910 to 1920. The conflict resulted in a new national constitution and significant economic, political, and social reforms for Mexico.

Causes.

People from every social class participated in the Mexican Revolution for various reasons. The dictator Porfirio Díaz had dominated Mexico since 1876, and many people took up arms in support of democracy. Other Mexicans were concerned with Díaz’s land policies. In the hope of developing the economy, Díaz had helped large landholders take land from peasant villagers. Some villagers resented Díaz’s centralization of political power. They felt that the national government was intruding too much upon local life. Many urban workers objected to the government’s use of violence to break up labor strikes and thus help keep wages low. Other Mexicans complained that Díaz was granting the best economic opportunities to foreign investors, particularly those from the United States, instead of Mexican investors. Drought and economic depression also made life more difficult for many Mexicans after about 1907.

The revolution

began after Francisco Madero, a wealthy landowner, ran against Díaz in a presidential election in 1910. Madero stressed the need for greater democracy, and Mexicans greeted his candidacy with enthusiasm. Díaz responded by arresting Madero. Once Díaz’s reelection was secured, he had Madero released on bail. Madero then fled to Texas.

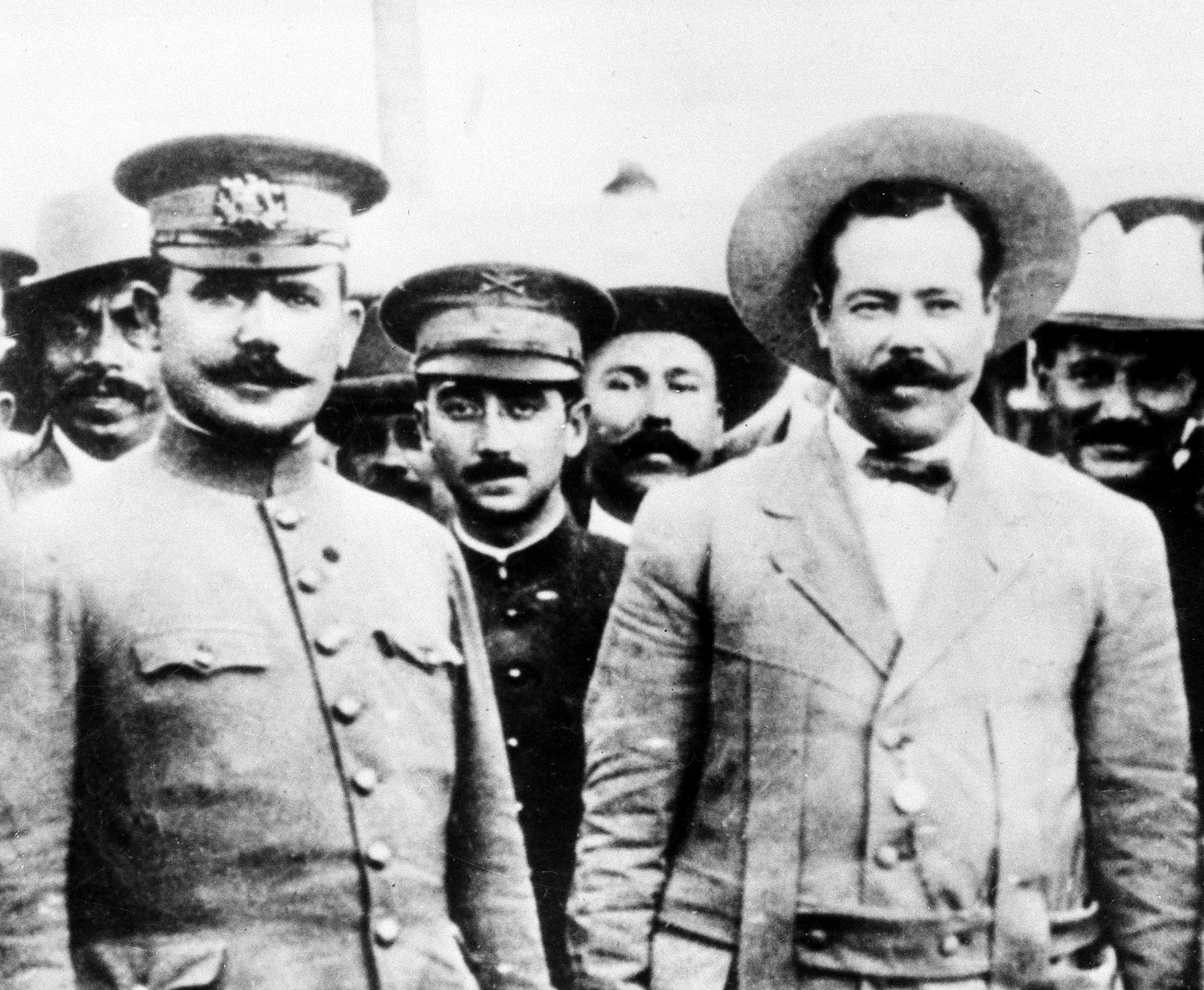

Madero called for an uprising against Díaz to begin on Nov. 20, 1910. The uprising grew gradually. Initially, it was strongest in the north, particularly in the state of Chihuahua. But there were also uprisings in many other parts of the country. By the spring of 1911, the rebels had applied enough pressure to cause Díaz to go into exile. Madero was elected president that fall.

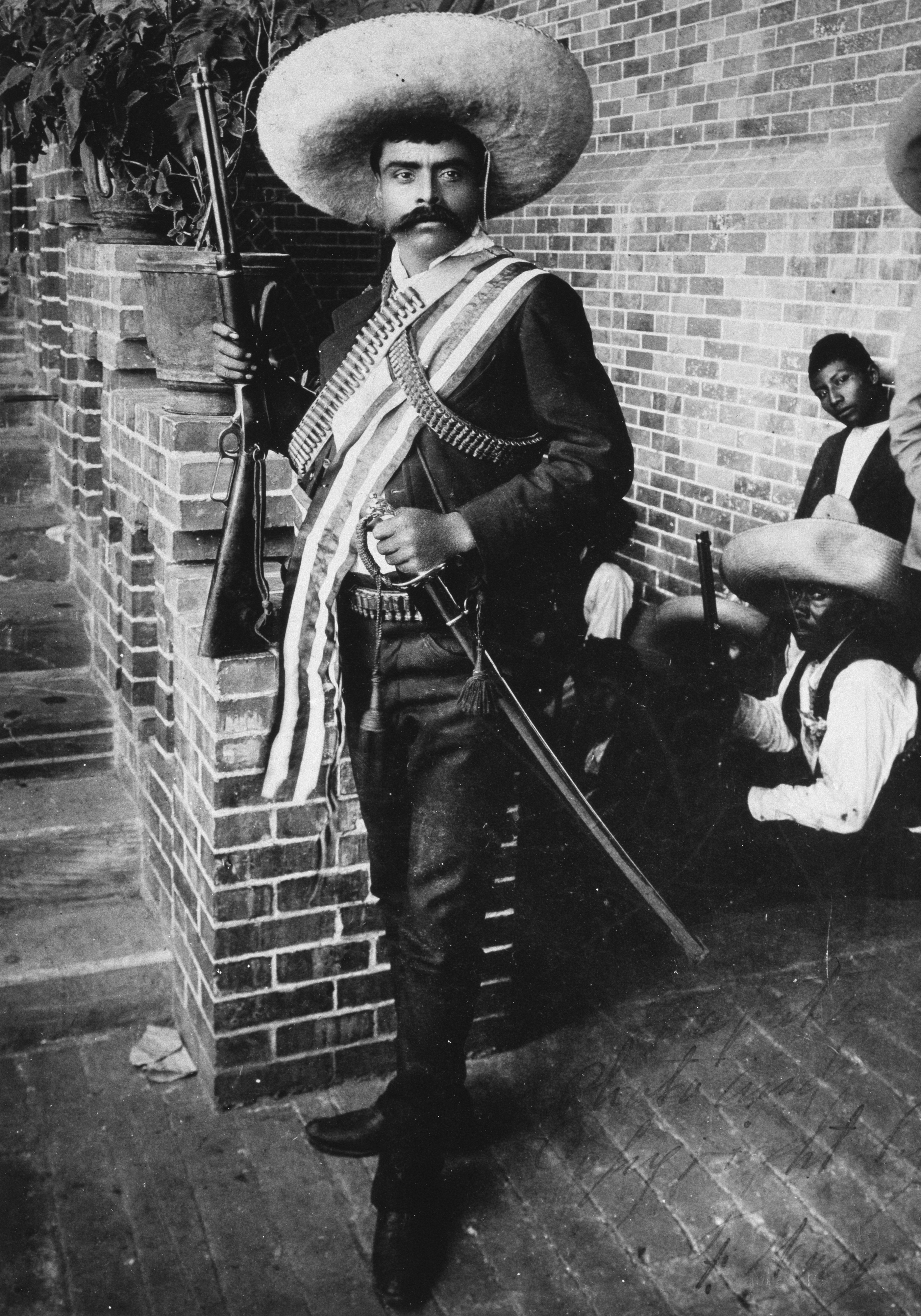

Not all the rebels agreed with Madero’s belief that democracy would solve Mexico’s problems. Many peasant villagers in central Mexico followed the rebel leader Emiliano Zapata in fighting Madero’s government. Their main complaint was that Madero had not quickly returned the land that they maintained had been stolen from them. People who favored a return to dictatorship also pressured Madero. One of them, General Victoriano Huerta, overthrew Madero in 1913. Huerta took over as president, and Madero was executed, probably on Huerta’s orders.

Following Madero’s death, revolutionary groups led by such men as Zapata, Venustiano Carranza, Francisco “Pancho” Villa, and Álvaro Obregón fought against Huerta’s government. These men came from different parts of the country and had various goals and ambitions. After defeating Huerta in 1914, they turned against one another. In 1915, the group led by Carranza defeated the forces of Villa, who was at that time allied with Zapata, in some of the revolution’s largest battles. Carranza took control of the government, though fighting against the forces of Villa, Zapata, and others continued until 1920. Perhaps a million people died in the war, and many others migrated to the United States.

Reforms.

Carranza supervised the creation of the Constitution of 1917, which addressed many revolutionary demands. It provided for land redistribution and rights for urban workers. The Constitution also called for restrictions on foreign investment, particularly in the mining and petroleum industries. Reforms often were slow, but they did materialize, especially in the 1930’s. The revolution’s clearest result was that after 1920, Mexico enjoyed remarkable political stability compared with other Latin American countries.