Colonial life in Spanish America is the story of Spanish explorers, missionaries, and settlers in what is now the southeastern and southwestern United States. It is also the story of the Indigenous (native) peoples the Spanish encountered. It describes the hardships and daily lives of Spanish colonists and the difficulties Indigenous groups faced under Spanish rule. This region’s Spanish American colonial period began in the 1520’s, with early attempts at settlement off the coast of Georgia. It ended in the mid-1800’s, after Spain had lost most of its colonies and the United States defeated Mexico in the Mexican War.

Historians often portray United States history as the gradual expansion of British territory westward, across lands that were thinly populated by Indigenous peoples. But the European settlement of North America began many decades before English colonists founded Jamestown in 1607. France and Spain also claimed much of the land on the continent. The French and Spanish sent out exploratory expeditions and set up a number of permanent settlements.

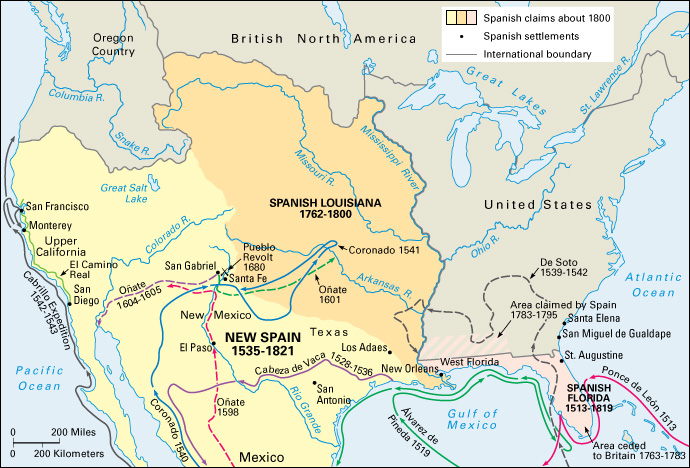

Throughout most of its colonial reign in North America, Spain claimed territory as far north as present-day Vancouver on the Pacific Ocean, and from Florida to Virginia on the Atlantic. The Viceroyalty of New Spain, as colonial Mexico came to be called, included most of Central America and about half of modern U.S. territory. It extended from Florida westward along the Gulf Coast to Texas, and from New Mexico to California in the Southwest.

Many histories of the colonial period focus on Spanish explorers and their quests for material gains. But the story of Spanish North America shows that the Spanish also intended to claim and settle the regions they explored. By the late 1500’s, Spanish colonials had established a number of missions, presidios (forts), and towns in North America. Most of these settlements failed. Even so, they left important legacies, including language, culture, religion, place names, and important buildings and architectural styles. The Spanish legacy also includes the introduction of livestock and the transmission of disease from Europe to the Americas.

Before the arrival of the Spaniards

At the time the Spanish arrived in Florida, the peoples of the southeastern and southwestern United States were as varied as the lands in which they lived. The land extended from the wet lowlands of the Southeast to the generally hot and dry Southwest and the rich coastal lands of California. The people living in these regions showed great diversity in culture and ways of life. Some got their food by hunting wild animals and gathering wild plants. Small groups of such hunter-gatherers usually had to move around from place to place to find enough food. Other people lived in complex societies in urban centers or cities. They made a living by growing beans, corn, cotton, and squash. The most important groups in these regions included the Apalachee and Timucua of Florida; the Caddo, Choctaw, Creek, Karankawa, and Natchez north of the Gulf Coast and in eastern Texas; and the Apache, Navajo, and Pueblo of the Southwest. Many small Indigenous groups speaking a wide variety of languages lived in California.

Scholars generally agree that the first humans to arrive in the Americas crossed the Bering Strait from Asia during the last Ice Age. They arrived at least 15,000 years ago and possibly as long as 35,000 years ago. Some groups, such as the Ancestral Pueblo (once known as the Anasazi), created advanced cultures with large urban centers. Most Native Americans, however, lived in smaller family-based groups. These groups tended to have close ties to nature and showed little interest in material wealth. Many scholars estimate that by the time the Spaniards arrived in North America, between 2 million and 7 million Indigenous peoples lived in the area north of what is now Mexico. Some scholars believe that as many as 18 million people lived in the region.

Exploration

In 1492, Christopher Columbus, an Italian navigator in the service of Spain, made landfall on the island of Hispaniola. The island is the site of present-day Haiti and the Dominican Republic. In 1521, an army led by the Spanish explorer Hernán Cortés conquered the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, the site of present-day Mexico City. From bases in the Caribbean and New Spain, Spanish forces set out to explore unknown lands farther north.

The Spanish crown, or monarchy, required leaders of these expeditions to obtain royal licenses. These licenses granted wide powers to the leaders, and would-be explorers competed for the privilege. Explorers organized expeditions to determine the extent of Spanish territory; to take control of new areas; to convert Indigenous people to Christianity; and to seek fortunes. From the early 1500’s, explorers focused on the exploration of “La Florida”––a region that included most of the present-day Southeast—and the area around New Mexico.

In 1512, Juan Ponce de León became the first officially licensed Spanish explorer in what is now the United States. The following year, he led a group toward “Bimini,” an island that the Spanish believed to lay north of Cuba. Bimini was rumored to have great wealth and a “fountain of youth” whose waters could restore youthfulness and vitality to the aged. Ponce de León and his party arrived at an area he named “La Florida” and claimed it for Spain. He failed to establish a permanent settlement, however.

Later expeditions succeeded in mapping Florida’s coastline. These groups included those of Pánfilo de Narváez in 1528 and Hernando de Soto from 1539 to 1542. These expeditions established no permanent colonies, but they led to the exploration and knowledge of much of the Southeast. Narváez’s 1528 expedition faced storms and attacks by Indigenous people, and Narváez himself drowned in the Gulf of Mexico. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca a survivor of that expedition, spent several years in eastern Texas. He and a few companions then traveled across what is now the southwestern United States and northern Mexico. In 1536, they finally met up with Spanish colonists in northwestern Mexico. Cabeza de Vaca eventually returned to Spain and wrote about his travels in a book published in 1542. Cabeza de Vaca’s survival helped inspire the expedition of Hernando de Soto, who explored Florida and what is now the southeastern United States beginning in 1539.

Spanish interest in exploring also extended westward. Shortly after the fall of Tenochtitlan in 1521, Hernán Cortés organized several expeditions to the north and west along the Pacific Coast. He hoped to locate the legendary “Strait of Anián” that supposedly would provide a direct trade route to China. From the 1530’s to 1540, expeditions led by Cortés himself, by Fortún Jiménez, and by Francisco de Ulloa provided the outlines of Mexico’s west coast and the peninsula of Baja California.

In 1542, Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo sailed up the coast of California. Cabrillo died in January 1543, but his expedition continued north to about the present-day Oregon border. From 1540 to 1542, Francisco Vásquez de Coronado headed the most significant expedition throughout the Southwest. Coronado and his party traveled through Arizona, New Mexico, Texas, Oklahoma, and Kansas. They searched for the fabled Seven Cities of Cíbola, and later, the city of Quivira. The Spanish believed that both locations were fabulously wealthy and full of gold, but they found no riches.

Settlement

The expeditions that Spain launched into North America throughout the first half of the 1500’s succeeded largely as reconnaissance, or surveying, missions. They were less successful at establishing permanent settlements. Few outposts lasted long. Disease, lack of food, poor weather, and conflicts with Indigenous groups made conditions difficult for the would-be colonists. In most cases, surviving settlers returned to Spain or colonial cities in Mexico or the Caribbean. From the mid-1500’s to the early 1600’s, however, exploration continued. Dozens of Spanish forts, missions, and pueblos (towns) began to mark the landscape.

The Spanish had three main motivations for settlement. First, they coveted the riches that legends said lay to the north of Mexico. They hoped to find mythical golden cities or conquer another wealthy empire, such as that of the Aztec or the Inca. Second, both the crown and clergy hoped to convert Indigenous peoples to Roman Catholicism. Conversion of Indigenous people promised the double reward of saving souls and legitimizing Spain’s conquest and colonization of Indigenous lands. Finally, Spanish settlement of the Southwest and Southeast would signal to other European powers––the British and French especially––that these were Spanish territories.

Early Spanish settlers came to the Viceroyalty of New Spain and other parts of North America for a variety of reasons. Among Spain’s wealthy families, only the oldest son had inheritance rights. Some younger sons, therefore, sought opportunities overseas. Commoners also looked to the New World for economic opportunity and the chance to improve their social standing. Others traveled as soldiers or as members of religious orders. Many of the early immigrants to Spanish America came from Castile, in central Spain. Large numbers of immigrants also came from Andalusia, a region in southern Spain, and Extremadura, in western Spain.

Spanish Florida.

The first European settlement in what is now the United States was the Spanish settlement of San Miguel de Gualdape in La Florida. Scholars believe that Lucas Vásquez de Ayllón established this colony in 1526 on or near Sapelo Island, Georgia. Ayllón brought about 600 settlers and nearly 100 horses to the site. However, lack of food, conflicts with Indigenous Americans, and disease caused many deaths. The settlers abandoned the town after just a few months. Only about 150 survivors returned to colonies in the Caribbean. In 1559, Tristán de Luna y Arellano also founded a short-lived colony, in Pensacola on Florida’s panhandle. The colony began with about 1,500 settlers, but a hurricane destroyed most of the supply ships before they were even unloaded. The colony never recovered, and the settlers abandoned it in 1561.

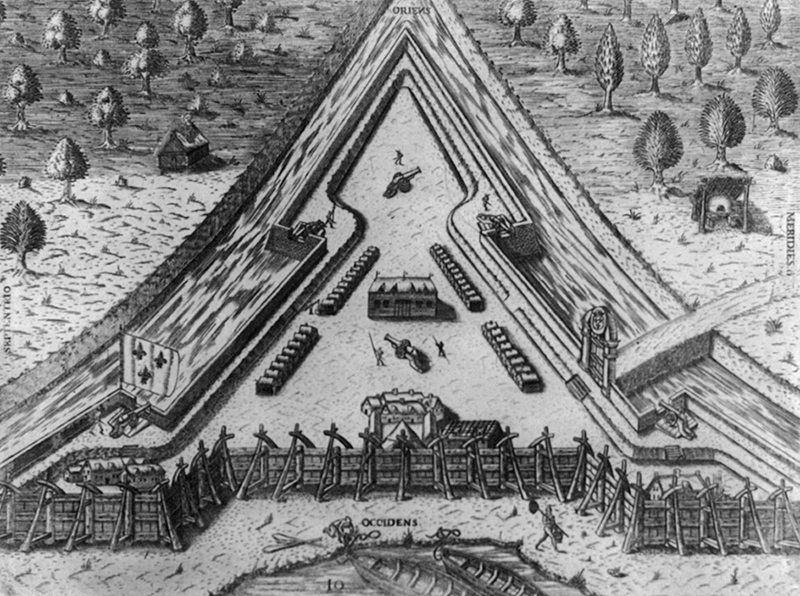

Florida’s first permanent Spanish settlement was that of St. Augustine, the oldest continually occupied town in the United States. Pedro Menéndez de Avilés established the colony in 1565 in what is now northeastern Florida. The Spanish founded the colony to help defend their claim to the region against rival claims by the French.

In 1562, French settlers led by Jean Ribaut had explored the nearby St. Johns River and claimed the territory for France. They then headed north and established a short-lived settlement at what is now Parris Island, South Carolina. In 1564, René Goulaine de Laudonnière, who had been Ribaut’s second-in-command, returned to the St. Johns River with another group of French settlers. He established Fort Caroline near what is now Jacksonville, Florida. Ribaut joined them in 1565. After the Spanish founded St. Augustine, they drove the French settlers out of Fort Caroline. The Spanish founded another settlement, Santa Elena, on Parris Island in 1566. The town served as the capital of La Florida for about 20 years. During that time, Santa Elena and St. Augustine were Spain’s two main settlements in La Florida. In 1586, the English privateer Francis Drake attacked and burned St. Augustine. Spanish authorities then decided to concentrate colonizing efforts in one place. In 1587, they abandoned Santa Elena and moved its settlers and goods to St. Augustine. St. Augustine remained the focal point of Spanish settlement in La Florida until 1763, when Spain ceded Florida to Britain (now also called the United Kingdom).

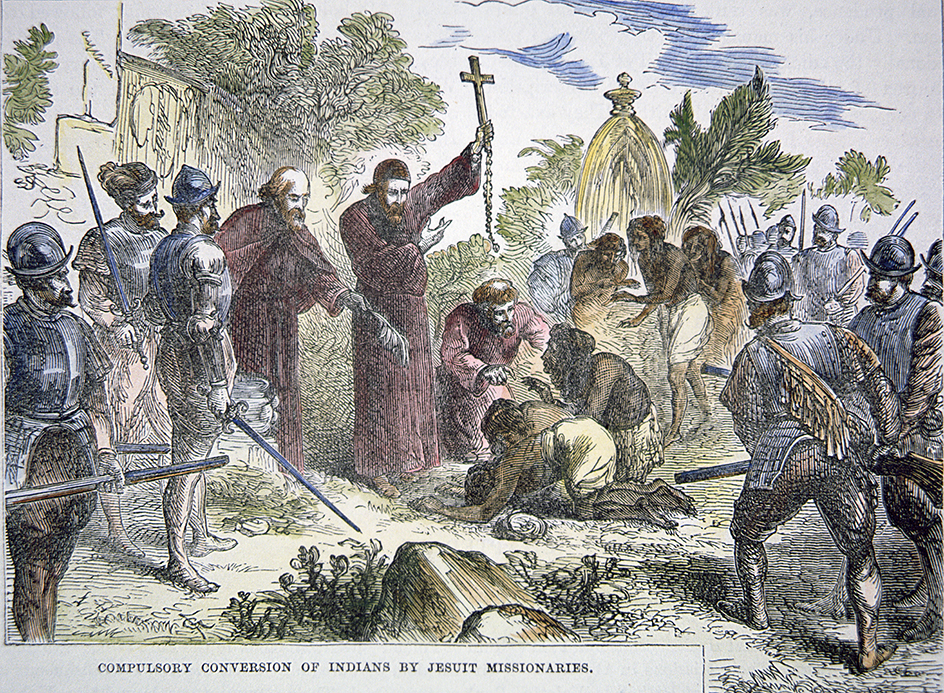

Missionary activity dominated later settlement in Florida. Between 1566 and 1572, missionaries of the Jesuit order, a Roman Catholic religious order, established missions from Virginia to the Gulf Coast. Over time, however, they experienced much hardship, and most of the missions soon failed.

After the Jesuits came missionaries of the Franciscan order, a religious order based upon the teachings of Saint Francis of Assisi. The Franciscans adopted the strategy of building mission churches in Indigenous American villages. By the 1670’s, there were more than 30 Franciscan mission churches, and more than 13,000 Christian Indigenous people, throughout Florida, Georgia, and part of Alabama. The Florida mission system greatly aided Spanish settlement in the area. But these settlements, like their predecessors, faced a number of problems. Attacks by Indigenous groups, raids by other Europeans, and disease led to the collapse of the missions. By 1700, only St. Augustine, with its surrounding villages, and Pensacola, just reestablished in 1698, remained intact.

New Mexico.

The discovery of silver mines in northern Mexico prompted Spanish officials to pursue settlement of the American Southwest. The Spanish called this area “New Mexico,” and they hoped that they would find an empire there similar to that of the Aztec. Explorers did encounter a highly complex, urban society in that of the Pueblo people. But the riches the Spanish sought continued to escape them. Beginning in the late 1590’s, Juan de Oñate Salazar established permanent settlements in the area. The Spanish king had granted Oñate a royal license to explore and settle the region. Like many other conquistadors (conquerors), Oñate used most of his personal fortune to settle the territory of the Pueblo—present-day New Mexico and parts of Texas. In 1598, Oñate set up his base in the Pueblo village of Ohkay Owingeh, which he renamed San Juan de los Caballeros. Soon afterward, he shifted the settlers to another nearby village, which he renamed San Gabriel de Yunque. He sent out a number of expeditions in search of the legendary city of Quivira and the Strait of Anián. San Gabriel served as the capital of Spanish New Mexico until it was moved to Santa Fe in 1609 or 1610.

From their base in Santa Fe, Franciscan missionaries began establishing churches throughout New Mexico during the 1620’s. By 1629, they had founded about 50 churches and monasteries and claimed thousands of converts. Like the Florida missions, however, these missions faced major challenges. Historians believe many Indigenous American groups agreed to convert for material gain, and eventually they rejected the friars’ efforts.

Texas and the Gulf Coast.

In 1519, the explorer Alonso Álvarez de Pineda sailed along the coast of the Gulf of Mexico from Florida to northern Mexico. He claimed lands along the gulf, including the area of Texas, for Spain. Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, one of the survivors of the Narváez expedition, explored the area in the 1520’s and 1530’s. Settlement of this region did not begin, however, until the late 1600’s. There, as in Florida, an increasing French presence in the area spurred Spanish settlement. In 1685, Spanish officials became alarmed by the news of a French settlement by René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle, near Matagorda Bay, Texas. Spain feared that the French outpost could threaten Spanish holdings in both Florida and New Mexico and weaken their control over the Gulf of Mexico. The Spanish reacted by establishing missions in East Texas. Within three years, however, the missions were abandoned.

The Spanish renewed their interest in Texas in 1699, after the French established a settlement near the mouth of the Mississippi River. France and Spain formed an alliance in the early 1700’s that prevented Spanish forces from attempting to drive the French from the area. This arrangement allowed the French to gain a permanent foothold on the Gulf Coast. Further French activity in the area, however, led Spanish officials to devote more resources to establishing missions, forts, and towns throughout East Texas. In 1716, the Spanish government appointed Martín de Alarcón as governor of Texas. He helped found San Antonio in 1718. In 1729, Spain designated Los Adaes, in present-day Louisiana, as the Texas capital.

Upper California.

As in Texas, the Spanish did not settle in what is now the state of California until later in the colonial period. By the mid-1540’s, Spanish explorers had charted the California coast and identified some bays that provided good natural harbors––San Diego and Monterey in particular. Even so, the Spanish displayed little interest in the region. In the mid-1700’s, however, reports of British and Russian trading activities on the California coast gained the attention of the Spanish. The Spanish called this region Alta California, meaning Upper California. In the 1530’s, they had colonized Baja California, or Lower California, now part of northwestern Mexico.

The colonial official José de Gálvez organized and ordered the pacification of Indigenous peoples in California. The Spanish government used the term “pacification” to refer to its official policy of trying to bring new regions and Indigenous groups under its rule by peaceful persuasion rather than outright conquest. Following practices carried out in Florida, Texas, and New Mexico, Gálvez ordered Franciscan friars to establish missions to bring about pacification. In 1769, the Franciscan missionary Saint Junípero Serra and the explorer Gaspar de Portolà set out with orders to establish missions in San Diego and Monterey. By 1823, the California mission system had 21 missions that extended from San Diego to San Francisco.

Ways of life in colonial Spanish America

Government and law enforcement.

Most of the early settlement of Spanish North America was carried out by adelantados. The adelantado was an office granted by royal license to individuals who agreed to fund and organize the exploration, settlement, and defense of a particular area. In exchange for these efforts, the adelantado received wide powers as the military governor of the region. Adelantados had direct ties to the crown, and they thus could act independently of the viceroy of New Spain. The viceroy was an official who ruled in the name of the king.

The adelantado of New Mexico, Juan de Oñate, had the power to distribute encomiendas, or grants of tribute collected from Indigenous villages, to his followers. In return, the encomenderos, the people granted such tribute, were supposed to protect Indigenous people and teach them Christianity. In New Mexico, tribute usually consisted of a set amount of corn, blankets, or animal hides. Sometimes, the encomenderos also forced Indigenous people to work for them as a form of labor tribute, although Spain had tried to outlaw the practice in the 1500’s. In practice, the encomenderos often treated Indigenous people harshly. The encomienda system inspired much resistance.

A different system governed St. Augustine. The city maintained a garrison of paid soldiers who forced Indigenous laborers to work for the Spanish. This arrangement, called the repartimiento system, required Indigenous peoples to labor on public works projects in exchange for a small wage. The repartimiento system, like the encomienda system, also led to severe abuses.

Throughout the colonial period, most towns and cities remained under military rule. The administration of justice took place mainly through military courts. The crown required civilian settlements to set up town councils, or cabildos. However, only a few settlements ever had them. Where cabildos existed, local people had an opportunity to participate in the political process. Most colonial outposts, however, remained military in nature well into the 1800’s.

Housing.

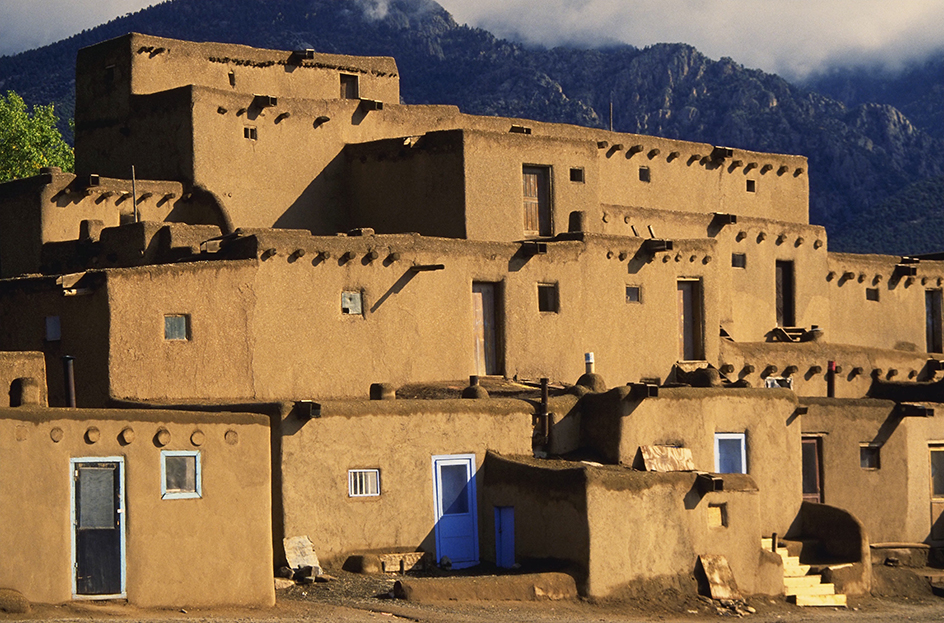

In Florida, most Indigenous Americans lived in small villages. In these communities, circular buildings with palm thatch roofs served as council houses or ceremonial centers. In the Southwest, Pueblo towns were more densely populated. They featured apartmentlike buildings three or four stories high. The buildings, which were made of adobe (sun-dried bricks), surrounded a central area that contained a kiva, or ceremonial chamber, for worship.

As in Spain, the colonists built their cities around a central plaza and laid out the streets in a grid pattern. Some settlers, however, chose to live away from the city centers. The colonists tended to construct buildings that followed Spanish architectural styles from different areas of Spain. In Florida, for example, houses had long verandas (covered porches) and balconies like houses in northern Spain. In New Mexico, many houses were built around a patio, or open court, as was the style in southern Spain.

Although the architectural styles came from Spain, the colonists used local materials to construct their buildings. In Florida, builders constructed walls of coquina, a shell stone; or tabby, a hardened mixture of water, lime, crushed shells, and sand. Most Florida structures had palm thatch roofs. In New Mexico, the Spanish constructed buildings of adobe. These buildings had wood-beam ceilings covered with layers of saplings, straw, compacted earth, and a final coating of plaster. Generally, the interiors of Spanish colonial houses were plain and had few furnishings. Most had packed earth floors, built-in benches and cabinets, and a few movable wooden pieces. Local carpenters created some furniture. The colonists also imported tools, hardware, and some household goods from Spain or Mexico. Wealthy people slept on plank beds. Commoners used sleeping mats on the floor.

Food and clothing.

Prior to the arrival of the Spaniards, Indigenous Americans along the frontier cultivated beans, corn, cotton, and squash. Spanish colonists, especially mission friars, sought to make Indigenous Americans cook and eat like Spaniards. The Spanish introduced a number of European crops to the Americas. They also brought with them many domesticated animals, such as cattle, chickens, horses, pigs, and sheep. Spanish influences thus had a significant impact on the diet of Indigenous people.

In addition to traditional crops, Indigenous peoples began widespread cultivation of many European plants, including melons and wheat. They enjoyed a variety of European fruits, such as apples, apricots, cherries, peaches, and pears. The Spanish also introduced the cultivation of some crops, such as tomatoes and chili peppers, that had been grown by Indigenous people in other parts of the Americas, but not as far north as what is now the United States. Indigenous staples such as the tortilla remained popular, and colonists adopted those foods as well. For their part, colonists made an effort to maintain their traditional diet through the cultivation of European plants and animals. But everyone, especially commoners, turned to native crops as well. They prepared Indigenous American dishes and drinks such as tamales, corn meal dough steamed in corn husks and usually filled with meat; posole, a corn and meat stew; elote, roasted or boiled corn on the cob; chocolate; and atole, a corn-based hot drink or porridge.

Spanish colonists, especially missionary friars, often complained that Indigenous people wore too little clothing. As with food and architecture, colonists sought to preserve European styles of dress on the frontier. They brought garments of linen, silk, and velvet, as well as hats, stockings, boots, and shoes for special occasions. For daily wear, however, colonists often adopted Indigenous American styles and materials, such as moccasins and garments made of buckskin.

Religion and education.

Religious concerns played a crucial role in the exploration and settlement of Spanish North America. In 1493, Pope Alexander VI divided jurisdiction (legal authority) over the new discoveries being made by Spanish and Portuguese explorers. Spain would have rights to explore and claim lands west of a set line, and Portugal would have similar rights east of the line. In return, the pope charged the rulers of those nations with spreading the Catholic faith in the new lands. The following year, the Treaty of Tordesillas between Spain and Portugal moved the line Alexander had specified farther west. The spreading of Catholicism made Spanish claims to the Americas legitimate in the eyes of the pope. Catholic conversion efforts also intensified in response to the Reformation, a religious movement of the 1500’s that led to Protestantism. Other European nations, however, never recognized the claims of Spain or Portugal to exclusive rights to explore or claim lands in the Western Hemisphere.

The Franciscans established numerous missions on the frontier. They braved extraordinary difficulties to convert Indigenous Americans to Catholicism. Franciscans established chains of missions throughout Florida, New Mexico, and Texas in the 1600’s and throughout Upper California in the 1700’s. Many missionaries learned the languages of Indigenous people and tried to relate Christian concepts to traditional forms of belief. Others believed that the best way to mold Indigenous Americans into good Christians was to teach them to dress, eat, cook, and live like Europeans.

Education in colonial settlements took place mainly in the missions and among religious personnel. St. Augustine had a school for Spanish children as early as 1606. A secular (nonreligious) school opened there in 1787 that taught children, probably only boys, of both Spanish and African descent. Students arrived at 7 a.m. They went home for lunch at noon and returned at 2 p.m. School ended at about sunset. They studied the alphabet, reading, writing, arithmetic, and Christian doctrine.

Transportation and communication.

Most transportation routes among colonial settlements developed along trails long used by Indigenous Americans. Prior to the arrival of the Spanish, a number of important trails linked population centers in the Southeast and Southwest. For example, trails linked New Mexico, the Great Plains, and the Pacific Coast with central Mexico. These trails provide evidence of a well-developed trade network among peoples in the precolonial era.

Spaniards took advantage of this network, using the trails for exploration, settlement, and communication. They often widened them to accommodate carts and mule trains. Many of these trails, such as the Chihuahua trail, later became part of El Camino Real, Spanish for the Royal Highway. Several such highways branched out from Mexico City to different parts of Spain’s empire. The Chihuahua trail was part of the route to New Mexico. Gaspar de Portolá and Junípero Serra cut new trails along the California coast. Soon, other explorers set up an overland route between Mexico City and the chain of missions established in Upper California.

Overland caravans that arrived from Mexico City supplied Spanish settlements in the Southwest. During the 1600’s, for example, a caravan of oxcarts with a military escort arrived in Santa Fe every three years. By the mid-1700’s, the official caravans came yearly. These caravans brought official correspondence; tools, hardware, and cooking utensils; and items needed for religious services, such as wine, candles, and musical instruments. They also brought clothing, footwear, and hats; and food items such as almonds, cinnamon, flour, oysters, pepper, raisins, saffron, and sugar. The early colony at St. Augustine, on Florida’s coast, received supplies by ship three times a year.

The arts.

Artistic production in Spanish North America centered mainly on the church. Public buildings and individual homes tended to be plain, with few decorations. But some mission churches had valuable paintings, statues, and silver ornaments imported from Spain or central Mexico. Some local arts developed and flourished under the Spanish. In New Mexico, artists painted elk hides and carved santos (wooden figures depicting Christian saints). They also produced retablos (painted or carved wooden panels designed to be displayed behind church altars).

The economy.

For the most part, Spanish settlements in the United States had difficulty supporting themselves. Instead, most of the major settlements relied on supply ships or caravans for basic necessities. The crown spent large sums each year paying the situado, or subsidy, to maintain the settlements.

A number of factors hindered or prevented economic growth. First, as defensive outposts on the fringes of the Spanish Empire, these settlements failed to attract large numbers of settlers. Would-be colonists were afraid of the hardships they might suffer. In most settlements, lack of settlers and enduring hostilities from both Indigenous groups and European rivals created poor conditions for economic growth. Furthermore, agricultural and crafts production in colonial settlements depended on local labor, but many Indigenous Americans only worked against their will.

The trade policies of the Spanish Empire further restricted economic growth. Spain prohibited trade with foreign powers and limited opportunities for colonists to start businesses. The inefficiency of Spanish imperial trade, combined with high transportation costs, contributed to the high cost of overseas goods. For overland routes to Texas, California, and New Mexico, traders had to transport overseas goods from Mexican ports––Veracruz for Atlantic trade or Acapulco for Pacific trade––through Mexico City, then north on El Camino Real. Transport was thus expensive, with traders having to pay many people along the way as well as customs duties (taxes on imports). Ships called at St. Augustine and Pensacola in Florida but charged high prices for their goods.

Some of the California missions produced agricultural surpluses, and the city of New Orleans eventually developed exports in furs, hemp, hides, and sugar. But few of the Spanish settlements ever gained self-sufficiency, much less produced a profit.

Spaniards and Indigenous people

In the early years of Spanish exploration, local people were often initially friendly and helpful. In many cases, Indigenous people served as interpreters for expeditions. They also saved survivors of struggling colonies from starvation and illness by providing food, shelter, and medicines. Spanish greed, demands, and disrespect of local peoples, however, soon eroded the initial goodwill. In many areas, Indigenous people began to resent the presence of the Spanish. Some began to actively resist Spanish settlement. As reports of Spanish slave raiding, rape, and other cruelty spread throughout the frontier, local groups began to greet Spanish explorers with distrust and outright hostility.

The encomienda system, which led to the overwork and abuse of many Indigenous people, made the situation worse. In the 1530’s, the Spanish crown began efforts to outlaw the encomienda in the central regions of the Viceroyalties of Peru and Mexico. Encomiendas and military rule, however, continued in outlying frontier regions such as Florida and New Mexico. In 1573, the crown issued rules called the Ordinances of Discovery. These rules prohibited the exploration of new territories without a royal license. They also required that expeditions seek “pacification” of these areas rather than outright military conquest. The rules thus emphasized the peaceful incorporation of lands and peoples into the Spanish Empire.

In practice, however, the rules had little effect on the treatment of Indigenous people. Both missionaries and government officials depended on local labor to produce agricultural products and crafts. Many of the Europeans relied on abusive forms of control and punishment. A number of factors limited the crown’s ability to crack down on such abuses. Communications were slow, and the crown had few ways to hold wrongdoers responsible. Thus, corruption became an ingrained part of the colonial system, particularly in the 1600’s. Finally, unlike the well-supplied British and French, Spanish settlements had little to offer local peoples in the way of goods to draw them into alliances.

The Spanish abuse of local peoples resulted in numerous small rebellions in New Mexico and Florida throughout the 1600’s. The Pueblo Revolt of 1680 was the most successful and violent of these uprisings. This revolt, led by a Pueblo man named Popé, was a coordinated attack against all Spaniards in New Mexico. It succeeded in expelling the Spanish from the region for about 13 years. In 1693, Diego de Vargas reoccupied Santa Fe. In Florida and other parts of the Southeast, the English allied with Indigenous Americans to attack Spanish missions. By the early 1700’s, Spanish missionary activity in Florida had nearly ended.

The end of Spanish rule

Spanish claims to the northern reaches of what is today the United States and Canada were always uncertain. Spain backed these claims with settlement only to offset competing claims from the British, French, or Russians. In contrast, Spain had for centuries continuously occupied many settlements in Florida, Texas and the Gulf Coast, New Mexico, and California. Nevertheless, throughout the 300 years of Spanish rule in New Spain, these settlements remained colonial outposts with few resources, sluggish economies, and limited populations. Only St. Augustine, New Orleans, and Santa Fe grew into economic and political centers. Most outposts continued to rely on royal support to survive.

During the late 1700’s and early 1800’s, a number of events challenged Spanish claims in North America. Spain lost territory in 1763 at the conclusion of the Seven Years’ War with England. In the treaty that ended the war, Spain gave up Florida to the British in exchange for Cuba. The British had captured the Cuban port of Havana the year before. This loss was made more acceptable to the Spanish, however, when a secret pact with the French ceded Louisiana, including New Orleans, to Spanish control. Moreover, a peace treaty signed in 1783 at the end of the American Revolution forced Britain to return Florida to Spain, because of Spain’s support of the United States during the war.

In 1768, a rebellion organized by French settlers in New Orleans briefly ousted the Spanish governor of Louisiana, Antonio de Ulloa. Spain regained control a year later. In 1800, in another secret treaty, Spain returned sovereignty over Louisiana to Napoleon, the French leader. The Spanish had demanded that Louisiana remain under French control to create a buffer between British and Spanish holdings.

In 1803, however, Napoleon sold Louisiana to the United States for $15 million. This Louisiana Purchase led to a long boundary dispute between Spain and the United States. United States officials claimed that the territories of the Louisiana Purchase extended west to the Rocky Mountains and included Texas and West Florida. The Spanish rejected these claims but had little power to challenge them. The outbreak of wars of independence in Spanish colonies throughout Latin America had weakened Spain’s ability to negotiate. In the Adams-Onís Treaty of 1819, the United States forced Spain to accept the loss of Florida and give up any claims to all territories north of the 42nd parallel in exchange for Texas. Spain thus gave up claims to most of the Great Plains and what would become the Oregon Territory.

Mexico became independent from Spain in 1821 and soon lost much territory. The first loss was Texas, which had long served as a buffer zone between Spanish, French, and British interests in North America. Texas had been only sparsely populated under Spanish rule. In the 1800’s, however, the region became increasingly attractive to Anglo (English-speaking) settlers. The Anglos soon outnumbered their Mexican counterparts. In 1835, Anglo settlers staged a rebellion that called for the establishment of an independent Republic of Texas. The republic functioned until the United States annexed the territory in 1845. Texas then became the 28th state in the Union.

Mexico still considered Texas as part of its territory. After the United States annexed Texas, fighting broke out. The conflict is known in the United States as the Mexican War (1846-1848). Many scholars consider it an act of U.S. aggression. United States forces quickly defeated the Mexicans. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo ended the conflict on terms that favored the United States. Under the treaty, Mexico gave up its claims to Texas, and the United States gained lands that became known as the Mexican Cession. This region included California, Nevada, New Mexico, Utah, and parts of Arizona, Colorado, and Wyoming. In exchange for this territory, Mexico received $15 million. The United States also took responsibility for an additional $3 million in damage claims made by American citizens against Mexico.

In 1853, the United States gained additional border territory in the Gadsden Purchase. For $10 million, the United States acquired southern portions of Arizona and New Mexico. The deal helped establish a clear boundary between the two countries and provided a good southern railroad route to the Pacific Ocean.

The heritage of Hispanic America

Spanish colonial settlement in North America left a significant legacy in the United States. Two of the earliest permanent European settlements in the United States––St. Augustine, Florida, and Santa Fe, New Mexico––were of Spanish origin. Residents of St. Augustine celebrate this heritage each year in a festival that reenacts the expedition of Ponce de León. Each year in Santa Fe, a celebration marks the arrival of the Franciscans into New Mexico.

Spanish architectural traditions remain throughout the southeastern and southwestern United States. Prime examples include the missions of California, New Mexico, and Texas; the presidio of San Diego; the fort of San Marcos in St. Augustine; and Spanish government buildings in Santa Fe, St. Augustine, San Antonio, and New Orleans. During the 1900’s, American architects popularized the architectural features of these buildings. The Mission Revival style first began to spread in the 1890’s, while the more ornate Spanish Colonial Revival style developed in the early 1900’s. Both styles influenced building construction all across the United States.

Today, the Spanish names of towns, states, lakes, rivers, and other geographic features number in the thousands. Spanish is the second most common language spoken in the United States, following the cultural heritage of many of the country’s early inhabitants.