Lost Battalion was the name given to members of the United States 77th Infantry Division who were trapped behind enemy lines for five days during World War I (1914-1918).

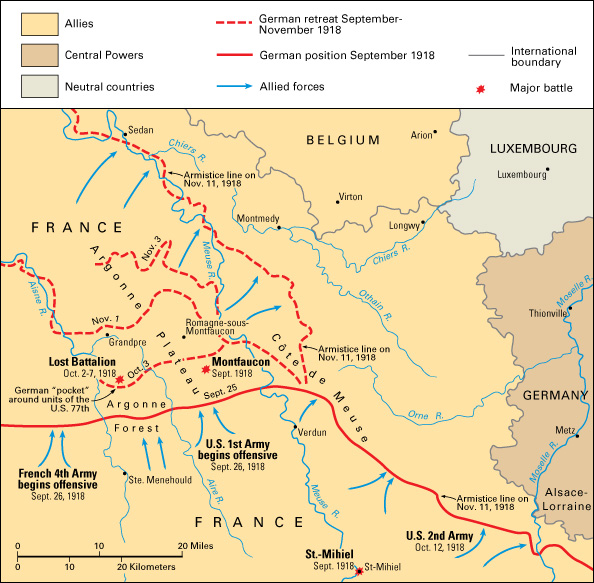

On Sept. 26, 1918, the U.S. First Army launched the massive Meuse-Argonne Offensive against the center of the German lines on the Western Front. The Western Front was a battlefront that stretched across Belgium and northeastern France. As part of the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, the 77th Division engaged the enemy on October 2. The 77th had originally been made up mainly of young immigrants from New York City, but many replacement troops, mostly from Western states, had recently joined them. Major Charles White Whittlesey led a force of infantry and machine gun companies from the 77th Division into battle near the French village of Binarville. The battalions to each side, however, failed to keep up, leaving Whittlesey and his troops isolated in what became known as “the pocket.” Only a small group of reinforcements, led by Captain Nelson M. Holderman, could reach the pocket early on October 3, before the Germans completely surrounded them. Short of supplies, the troops withstood relentless German gunfire and assaults for five days. On October 7, Whittlesey refused to reply to an appeal from the German commanding officer to surrender. That night, an American relief force arrived, and the Germans withdrew. Historians estimate that more than 600 American soldiers fought in the pocket. More than 100 were killed and a few were captured. Most estimates suggest that over half the remaining soldiers were wounded.

For his extraordinary bravery and leadership during the battle, Whittlesey earned the Medal of Honor—the highest military decoration awarded by the U.S. government. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel and treated as a hero upon his return home. Whittlesey, however, never recovered from the trauma of the battle, and he committed suicide in 1921.

Lost Battalion captains George G. McMurtry and Nelson M. Holderman were also awarded the Medal of Honor for their courageous efforts. Second Lieutenant Erwin R. Bleckley and First Lieutenant Harold E. Goettler both received the Medal of Honor posthumously (after their deaths). Bleckley and Goettler were aviators who were killed trying to supply the Lost Battalion from the air. First Sergeant Benjamin Kaufman and Private Archie A. Peck also were awarded their country’s highest honor for their bravery. Captain Eddie Grant, a former major league baseball player, died of wounds suffered while on a mission to rescue the Lost Battalion. A monument to the bravery and sacrifice of all the troops involved stands in Binarville.

A carrier pigeon named Cher Ami (French for Dear Friend) delivered a message from Whittlesey to redirect American artillery fire that was falling on his unit. Cher Ami was severely wounded on his flight out of the combat area, but he survived to relay the message. After the pigeon’s death, his body was preserved and put on display at the National Museum of American History at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

The story of the isolated soldiers of the 77th Infantry Division has inspired numerous books. It was also the subject of motion pictures in 1919 and 2001, both titled The Lost Battalion. During World War II (1939-1945), the 1st Battalion of the 141st U.S. Infantry Regiment was trapped behind enemy lines for a week during heavy fighting in eastern France. It too became known as the “Lost Battalion.”

See also Meuse-Argonne Offensive ; Whittlesey, Charles White ; World War I .