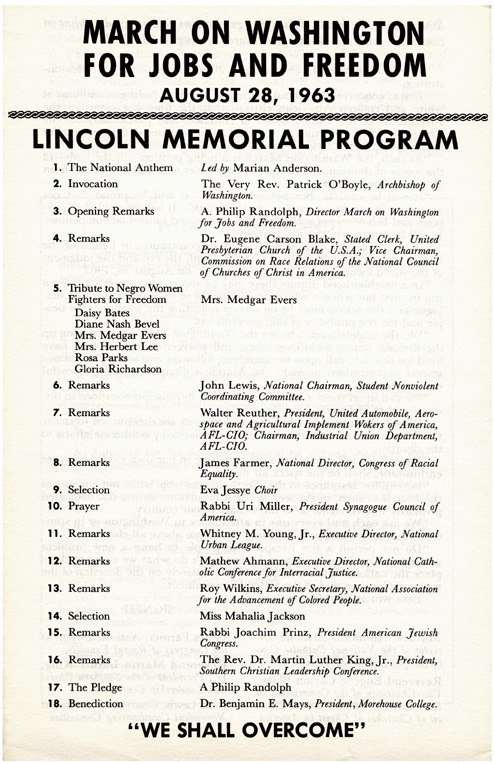

I Have a Dream is a famous speech given by the American civil rights leader Martin Luther King, Jr. King made the speech on Aug. 28, 1963, at the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, D.C. The address was shown on national television. It was the high point of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The purpose of the march was to call attention to unemployment among African American workers. The marchers also wanted to urge Congress to pass the civil rights bill that President John F. Kennedy had proposed. King’s speech explained the moral basis of the civil rights movement. It is considered one of the greatest speeches in history.

Loading the player...Excerpt from the speech “I Have a Dream,” by Martin Luther King, Jr.

To create his speech, King, who was a Baptist minister, drew on his knowledge of the Bible, the Emancipation Proclamation , the Gettysburg Address , and the Declaration of Independence . He quoted from or referred to all of these in his speech. The first half of the speech describes the racial injustice that King saw in the United States. The second half describes King’s dream for a future of equality and racial harmony. King had used parts of the speech in other speeches as early as 1956. A recording of an early version of the speech, which King gave at Booker T. Washington High School in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, on Nov. 27, 1962, was discovered at the Braswell Public Library in Rocky Mount in 2015.

King began his speech by noting the significance of the marchers’ gathering near the Lincoln Memorial, a monument that honors President Abraham Lincoln . Lincoln was called “the Great Emancipator” for his efforts to end slavery in the United States. King echoed Lincoln’s famous Gettysburg Address and referred to the Emancipation Proclamation as he began: “Five score years ago, a great American, in whose symbolic shadow we stand today, signed the Emancipation Proclamation. . . . But 100 years later, the Negro still is not free.”

King also referred to the words of Thomas Jefferson in the Declaration of Independence to point out what King regarded as another broken promise to African Americans: “This note was a promise that all men—yes, black men as well as white men—would be guaranteed the ‘unalienable Rights’ of ‘Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.’ It is obvious today that America has defaulted on this promissory note, insofar as her citizens of color are concerned.”

“Now is the time to make real the promises of democracy,” King announced. In a call to action, King described the civil, economic, and political inequalities African Americans continued to face, especially in the Southern States. See African Americans (The civil rights movement) .

King then said that even though African Americans “face the difficulties of today and tomorrow, I still have a dream. It is a dream deeply rooted in the American dream.” King told the crowd that he had a vision of a United States that was not divided along racial lines. As he described this vision, King emphasized the phrase “I have a dream” several times in the speech. He used this repetition to powerfully reinforce his message of hope. King again quoted Jefferson’s words in the Declaration of Independence: “I have a dream that one day this nation will rise up and live out the true meaning of its creed: ‘We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal.'” Also among King’s dreams was an America where his four children would be judged not “by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

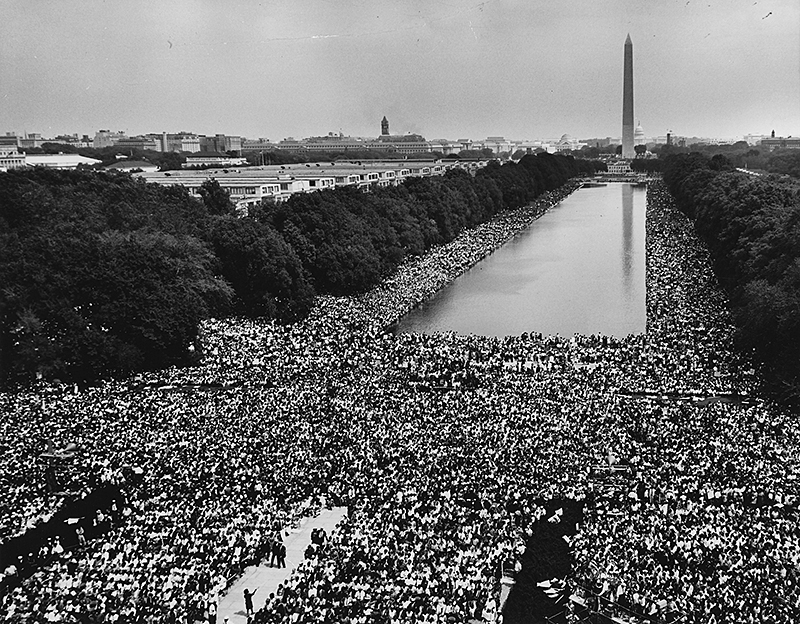

King then quoted from the U.S. national hymn “ America ,” repeating its refrain, “let freedom ring.” The crowd of 250,000 cheered wildly as King ended his speech: “And . . . when we allow freedom to ring, . . . we will be able to speed up that day when all of God’s children, black men and white men, Jews and Gentiles, Protestants and Catholics, will be able to join hands and sing in the words of the old Negro spiritual, ‘Free at last! Free at last! Thank God Almighty, we are free at last!’”

President Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, and Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson became president. Johnson persuaded Congress to pass the Civil Rights Act of 1964 .