Panic of 1837 was the first major economic crisis in United States history . It marked the beginning of a financial recession that brought ruin and misery to millions. This period came to be known as “the panic” for the worry it inspired throughout the country.

From 1834 to 1836, the United States underwent a period of rapid economic growth. Trade and agriculture flourished, leading to increased prices for crops, land, and enslaved persons to work the land. But international pressures—notably a rise in British interest rates—forced U.S. banks to raise their interest rates in 1836. Higher interest rates led to increased borrowing costs for manufacturers and thus reduced their demand for cotton and other crops. The economies of several Southern states were highly dependent on cotton. The drop in prices, together with a general surplus in the world cotton supply, would lead to a collapse in the U.S. cotton market.

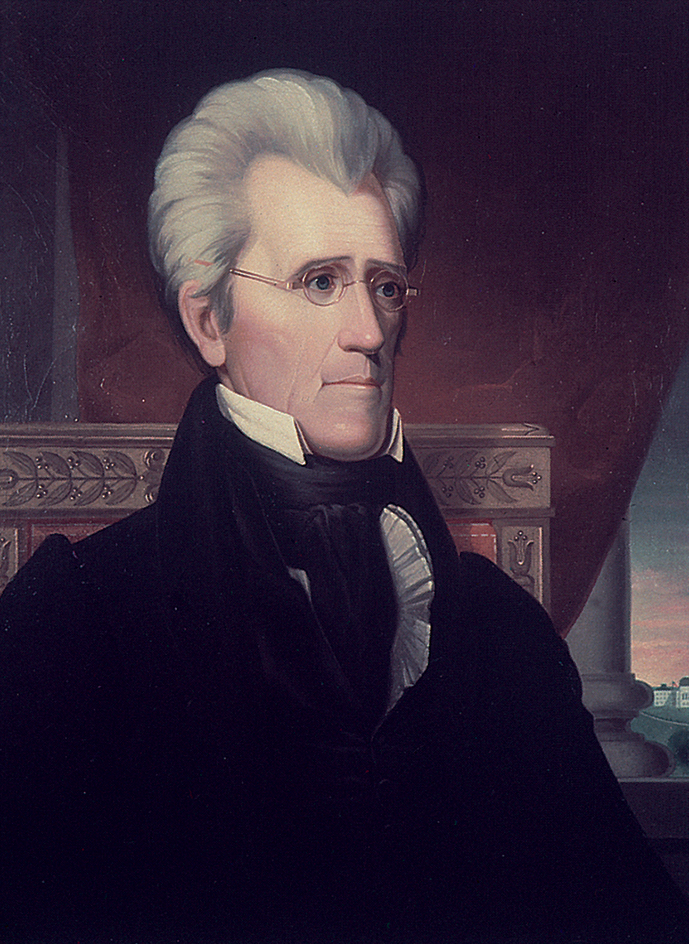

Domestic economic policies also contributed to the panic. During his last year in office, President Andrew Jackson unsuccessfully urged Congress to limit the sale of public lands to settlers. Americans, even many among the working classes, had engaged in widespread speculation (high-risk investment). Investments included public lands, canals, roads, and cotton. State banks and branches of the Bank of the United States contributed to the speculation, making vast loans without security in gold or silver. Unable to limit land sales, Jackson had issued an executive order called the Specie Circular of July 11, 1836. It required the government to accept only gold and silver—and not paper money—in payment for public lands. Banks could no longer make loans without security in gold and silver. Investors sought to exchange their bank notes for hard currency, which most banks held in insufficient reserve. By 1837, large-scale speculation had ended. But faltering markets, together with tighter currency policies, had put many banks at risk.

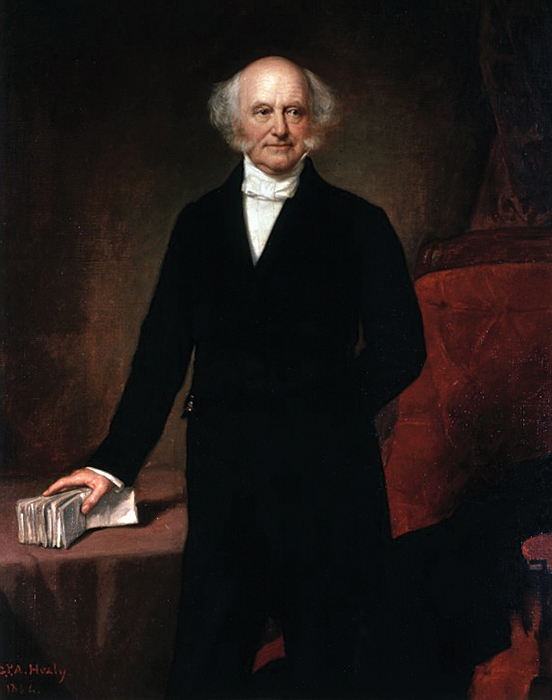

The financial crash came on May 10, 1837, just 67 days after President Martin Van Buren took office. Banks in Philadelphia and New York City were forced to close. Soon, every bank in the country did likewise. The first great depression in U.S. history had begun. Factories closed, and many people lost their jobs. People turned to the government for help, but Van Buren refused to provide aid. He believed in Thomas Jefferson’s idea that government should play the smallest possible role. “The less government interferes,” Van Buren explained, “the better for general prosperity.”

The Panic of 1837 placed Van Buren in a dangerous political situation, because he had pledged to limit the use of federal power. But he acted decisively to protect government funds, which were on deposit in private banks. He called Congress into special session and proposed that a treasury be created to hold government money. A bill putting this plan into effect was defeated twice, but it finally passed Congress on July 4, 1840. The battle over the treasury cost Van Buren the support of many bankers and bank stockholders. He especially lost support in the strong Democratic states of New York and Virginia. This loss crippled his bid for reelection.

The U.S. economy, particularly in the Cotton Belt—a cotton-growing region in the U.S. southeast—did not recover from the effects of the panic until the mid-1840’s. In addition to the economic consequences, the panic also greatly undermined public trust in the U.S. government.