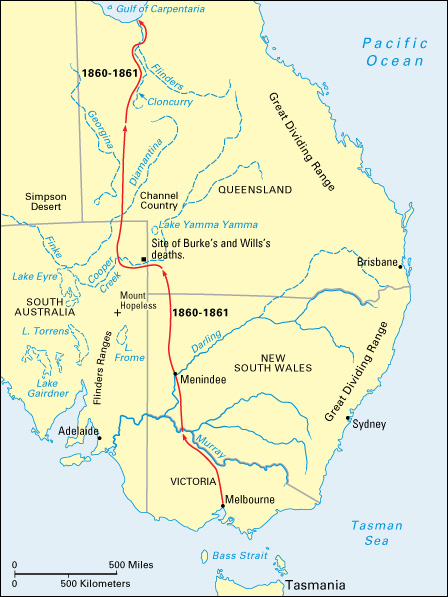

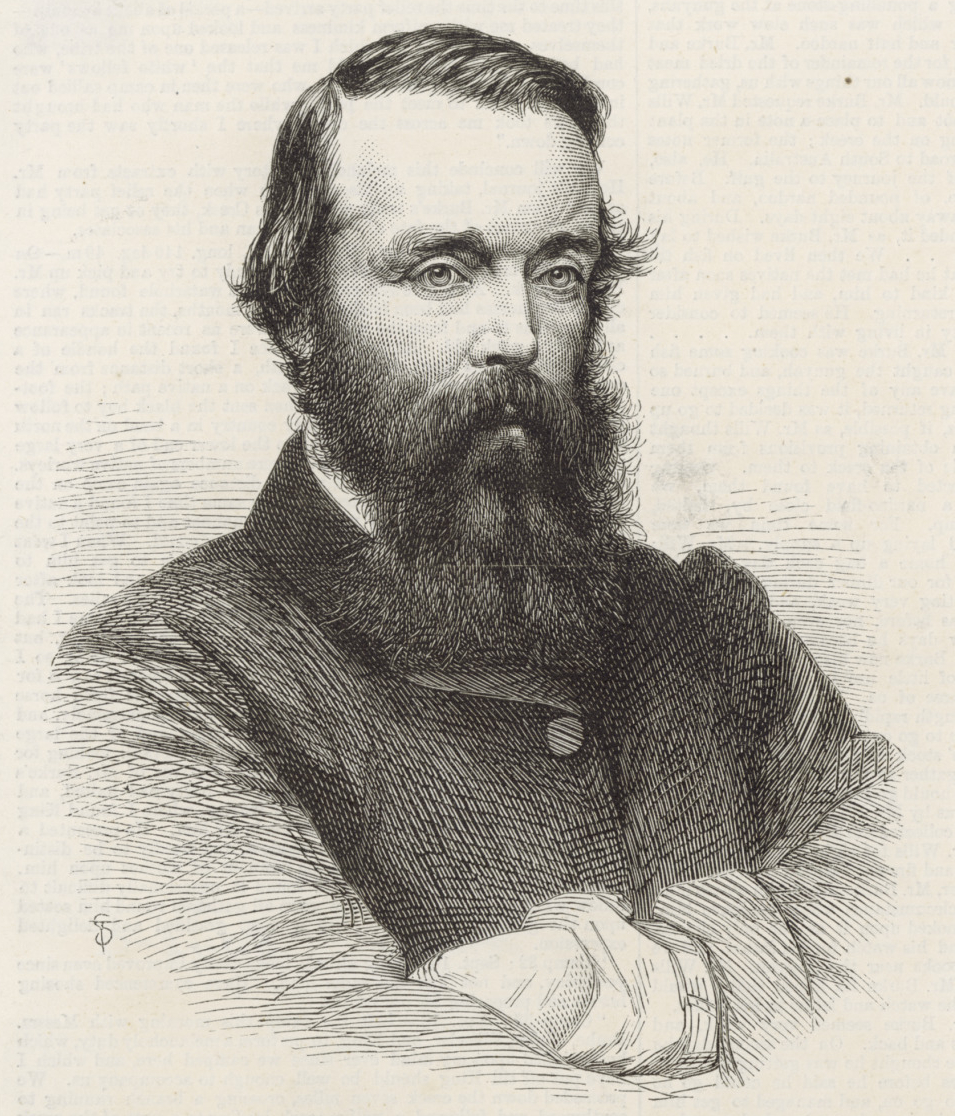

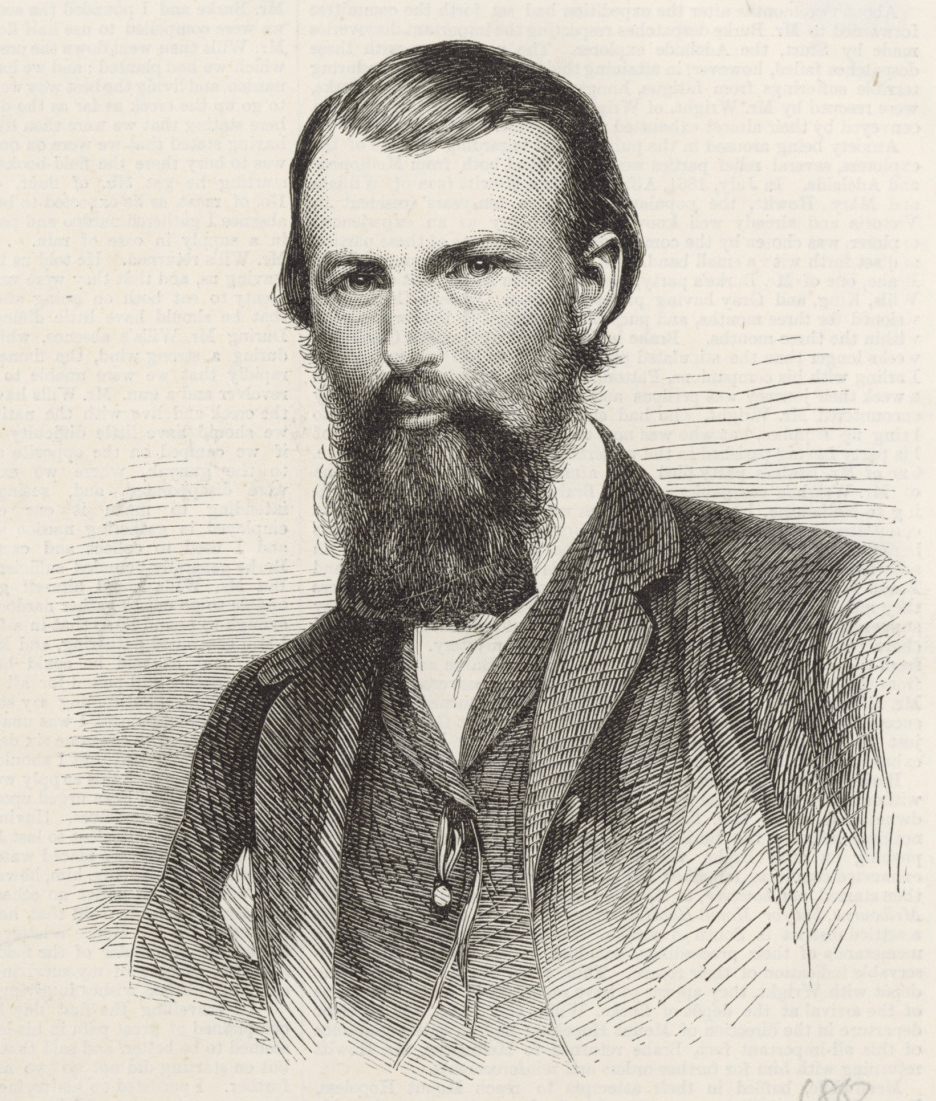

Burke and Wills expedition was the first journey by European explorers to cross the vast wilderness of Australia from the southern coast to the northern coast. The Irish-born explorer Robert O’Hara Burke led the expedition. The British-born explorer William John Wills plotted maps of their progress.

The Burke and Wills expedition began in Melbourne , Victoria , on Aug. 20, 1860. It completed its journey to the Gulf of Carpentaria on Feb. 11, 1861. The expedition’s route was about 2,000 miles (3,200 kilometers) long. The group journeyed north through New South Wales and Queensland , briefly crossing into South Australia. They followed the Darling River and made a base camp in Menindee, New South Wales, and another at Cooper’s Creek (now known as Cooper Creek) in southwestern Queensland.

Burke and Wills—along with Charles Gray, an ex-sailor and station hand, and John King, a surveyor’s assistant—became the first Europeans to cross Australia from south to north. However, the expedition was viewed as a failure due to the deaths of several explorers—including Burke, Gray, and Wills—who died on the return journey. The Burke and Wills expedition led to further European settlement of Australia’s interior.

Preparation and departure

At the time of the expedition, much of Australia had not been charted. The government of South Australia sought to establish a telegraph line across the continent. The government offered a large reward to the first people to make the south to north journey. The Victorian government and the Royal Society of Victoria funded the expedition, officially known as the Victorian Exploring Expedition. The expedition was one of the most expensive in Australian history. Burke had no previous experience in navigation or surveying land. However, the party was well-equipped, traveling with 27 camels and even an oak table. About 15,000 people gathered in Royal Park in Melbourne to watch the expedition depart.

Journey to the gulf

On Sept. 23, 1860, the party reached Menindee, New South Wales. A disagreement broke out. Burke chose to lead a smaller group of seven explorers to western Queensland. He left most of their supplies in Menindee with William Wright, a local man. He instructed Wright and the other expedition members left in Menindee to follow soon. However, Wright and his party did not leave for three months.

Burke’s group traveled to Cooper’s Creek. They arrived on Nov. 11, 1860. They established a depot along the creek, near the border between Queensland and South Australia. On December 16, Burke, Gray, King, and Wills separated from the party to travel to the Gulf of Carpentaria. William Brahe stayed behind at the depot. He was instructed to wait for their return for three months.

Burke, Gray, King, and Wills reached the Bynoe River, near the Gulf of Carpentaria, on Feb. 9, 1861. For two days, Burke and Wills attempted to reach the ocean from there alone, but their path was blocked by mangrove swamps. On Feb. 12, 1861, the four explorers started their return journey to Cooper’s Creek.

Return to Cooper’s Creek

Gray died of malnutrition on the return trip on April 17, 1861, about four days’ journey from Cooper’s Creek. Brahe had waited for four months for the party to return. Before leaving, he buried a supply of food and a note for the explorers under a coolabah tree. He carved directions into the tree, which became known as the “Dig Tree.” Brahe carved “DIG 3FT NW APR 21 1861” into the tree. Brahe left for Menindee on April 21. About nine hours after he left, Burke, King, and Wills arrived at the Cooper’s Creek camp. They found the supply of food by the Dig Tree. Instead of continuing on to Menindee, the three changed course to reach a different station. On April 22, they traveled southwest toward Mount Hopeless in South Australia.

Wright and his party left Menindee with the supplies on Jan. 26, 1861. On the way to Cooper’s Creek, extreme heat and illness forced the party to rest at the Bulloo River. There, between April 22 and 29, three men—Ludwig Becker, William Purcell, and Charles Stone—died of malnutrition and dysentery, an intestinal disease. On April 29, Wright’s party came across Brahe on their way to Cooper’s Creek. Brahe joined them, and they all arrived in Cooper’s Creek on May 8. On June 5, William Patton died.

Before traveling to Mount Hopeless, Burke, King, and Wills, buried their own message under the Dig Tree. They wanted to leave no trace so their message would not be uncovered by Aboriginal people. They covered their tracks so well, however, that when Brahe and Wright’s party arrived, they did not think the tree had been visited at all. Wills returned to the depot on May 27 and saw no sign that Brahe or the Wright party had come to look for them.

Exhausted and starving, Burke, King, and Wills went searching for the Aboriginal Yandruwandha people. Yandruwandha people had helped the explorers since their arrival in the Cooper’s Creek area. Wills told Burke and King to go on without him. Burke and Wills died of malnutrition between June 28 and the first few days of July, but historians do not know the exact dates. The men had also contracted beri-beri—a deficiency of thiamine and vitamin B1—from eating raw nardoo, a plant which has an enzyme that breaks down thiamine. The explorers had learned to eat nardoo from Yandruwandha people. However, Aboriginal peoples specially prepared nardoo in a way that eliminated the harmful enzyme. Some Yandruwandkha people found King and saved his life.

Conclusion of the expedition

Relief parties were sent from Queensland, South Australia, and Victoria to search for the explorers. Alfred Howitt and Edwin Welch led a Victorian relief party. On Sept. 15, 1861, they found King living with Yandruwandha people. They also found the bodies of Burke and Wills and gave them proper burials. Their remains were later relocated and re-buried in Melbourne, in Australia’s first state funeral, on Jan. 21, 1863. In their searches, the relief parties discovered grazing lands in Australia’s interior. This discovery led to increased European settlement of the interior.