Chariot racing was an extremely popular form of entertainment in ancient Greece , ancient Rome , and the Byzantine Empire . Charioteers raced two-wheeled chariots , normally pulled by two or four horses, around an oval arena. Some charioteers became rich and famous.

The first known written mention of chariot racing is in the Greek poet Homer’s poem the Iliad . The sport was part of the Olympic Games in Greece for about 1,000 years, beginning in 680 B.C. Competitors completed 12 laps around an arena called a hippodrome, which had a large post at each end to mark sharp turns. Remains of Greek hippodromes have been discovered at Delphi and Olympia . The owner of a chariot and horses usually employed a slave or hired a professional to drive them. Chariot racing was a significant feature of Greek religious festivals, such as the Panathenaea, honoring the goddess Athena , and the Isthmian , Nemean , and Pythian games. The winners received prizes, such as bronze and silver objects and large jars of olive oil.

In ancient Rome, chariot racing was the most important form of entertainment. As in ancient Greece, it often was associated with religious festivals. The Romans generally called their racing arenas circuses. The Circus Maximus was Rome’s greatest arena. It could hold about 250,000 spectators. A race day began with a musical procession of charioteers, images of the gods, and dancers and musicians. Starting gates called carceres were located at one end of the arena. The race began after the starter dropped a white cloth. The chariots raced five or seven laps around a central stone barrier called the spina. As in Greek arenas, a post (meta) marked the turning point at each end. Moveable gold sculptures of dolphins or eggs served as lap markers, to indicate the progress of the race. The winner of the race received money, a laurel wreath, and a palm branch.

Roman chariot racing had four main teams, or factions—the Blues, Greens, Reds, and Whites. Members of the public passionately supported their favorite factions, much like sports fans today. Fans bet on their teams, wrote slogans on walls, and used tablets with curses inscribed on them to try to influence races.

Roman charioteers wore jackets or tunics in the colors of their factions, and leather skull caps for safety. Unlike Greek charioteers, who only held the horses’ reins, the Romans also wrapped the reins around their bodies. They carried daggers to cut themselves loose in the event of a crash. Crashes were frequent because teams were allowed to block one another. Many Roman charioteers died young. However, a successful charioteer could become quite famous and wealthy. The Roman charioteer Diocles, who lived in the A.D. 100’s, retired with a fortune worth millions, and possibly billions, of dollars by modern standards.

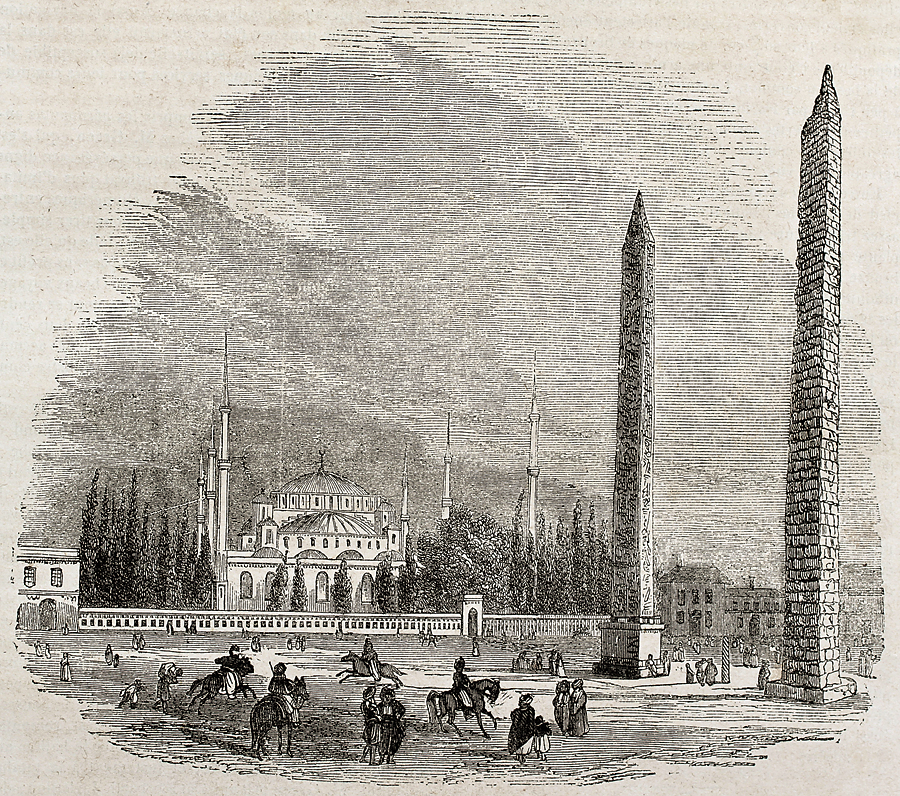

Chariot racing continued to be popular throughout the time of the Roman Empire, and during the early Byzantine Empire. The Byzantine Empire lasted from about 330 to 1453. Roman chariot-racing factions increasingly came to represent political and religious ideas. Violent fights erupted between factions. In 532, the Blues and Greens united to try to overthrow the emperor Justinian I . Chariot racing declined in popularity in the centuries that followed, but it continued in the Byzantine capital of Constantinople until the 1100’s. Today, elements of chariot racing are preserved in modern horse racing and harness racing .