Makassan, also spelled Macassan, were sailors and fishing crews from the port of Makassar (now part of Indonesia) who were among the first visitors to Australia. For hundreds of years, Makassan fishing crews sailed from what is now the Indonesian island of Sulawesi to Australia’s northern coast. Trade and contact with the Makassan crews influenced Australian Aboriginal society and culture throughout the 1700’s and 1800’s.

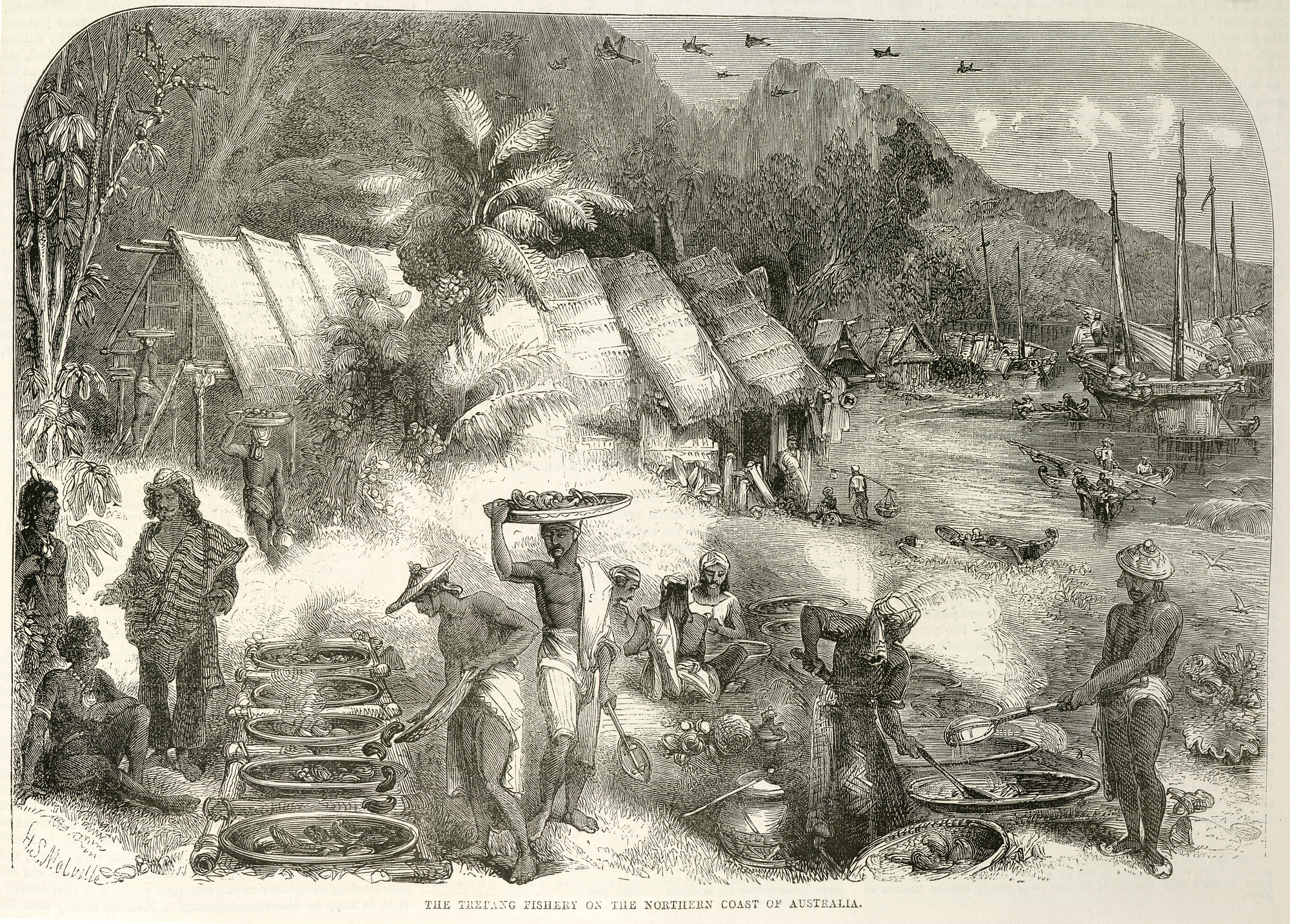

Makassan crews traveled in fishing boats known as praus. They came to the Australian coast to collect trepang. Trepang are edible varieties of sea cucumber, a type of animal with a long fleshy body that may look like a cucumber. The act of collecting them is called trepanging, and people who collect them are called trepangers.

The Makassan trepangers collected sea cucumbers from around December to April, as the timing of their sea journey depended on the monsoons (seasonal winds). While in Australia, the trepangers prepared the sea cucumbers for transport and sale in a complex process that included burying the trepang in the sand. As the crews carried out the preparation process, they spent much of their time along the shore. Upon their return to Makassar, the crews sold their catch to merchants in China, where the trepang was highly valued as a delicacy.

It is unknown when the Makassan first landed on the shores of Australia. Many historians suspect that they began trading with Aboriginal people in the early 1700’s. However, some archeological evidence and oral histories from local Aboriginal groups suggest that contact between Aboriginal people and the Makassan may have occurred as early as the mid-1600’s.

The Yolngu Aboriginal people of Arnhem Land, on the northeastern coast of Australia, had a significant trading relationship with the Makassan trepangers. Ideas from Makassan society, including elements of the Islamic religion, entered Yolngu art and culture. Makassan words and place names were integrated into the Yolngu language. Makassan traders introduced the Yolngu people to metal tools and weapons, including iron blades, knives, and spears. Yolngu people even accompanied the traders on their journey back to Makassar. Today, some members of the Yolngu people can also claim Makassan heritage. They are the descendants of Aboriginal women who had children with Makassan trepangers during their time in Australia.

By the late 1700’s, the trepang trade was a major export industry in Makassar and Australia. As European interest in the region grew, the Makassan also interacted with Dutch and British colonial officials. In 1883, South Australia, which governed the Northern Territory at the time, imposed new regulations on Makassan trepangers. Each prau captain had to purchase an annual license. Customs officers collected duties on the trepangers’ trade goods and rations. In 1906, the South Australian government stopped issuing licenses to the Makassan, effectively banning them from trepanging in the traditional coastal areas. The government hoped to bring the trepang industry under Australian control. In 1907, the Makassan trepanger Using Daeng Rangka sailed to Arnhem Land in the last prau known to visit Australia.